Aziz put down the newspaper and sighed. “This is bad, the situation is bad”. Sitting in his small tea shop, he had just finished his routine practice of reading out loud some articles from the local Urdu newspaper K2, that publishes on issues in Gilgit-Baltistan (one of the Pakistani parts of Kashmir). Normally this is much appreciated not only by some of the town’s senior residents with bad eyesight, but also by the German anthropologist who sometimes struggled to decipher the miniature Urdu letters. Aziz had just read about the new hike in petrol and gas prices that was announced by the national government and would only increase the inflation in Pakistan, which had been soaring at that point, with an annual food inflation rate of over 50 per cent. Daado (an older regular customer; all names changed) and I were sitting around the small table in Aziz’s shop, while his 25-year-old son Farhan stood behind the counter and silently listened to our conversation while he prepared more chai or checked his phone. Aziz and Farhan’s chai shop stood next to the KKH, the Karakoram Highway, that links Pakistan’s capital Islamabad to China’s Xinyang province, passing through Aliabad in Hunza, where I conducted ethnographic fieldwork between November 2022 and August 2023. During that time, I visited their shop nearly daily and became good friends with Aziz, Farhan and regular customers, keeping up with local news and gossip.

On that day at the end of February 2023, Aziz was not happy and folded away the newspaper. The headline stated that the IMF had imposed tight conditions on completing its current review phase that would release an urgently needed tranche of $1.1 billion to Pakistan. The country had been undergoing a constitutional crisis since former Prime Minister Imran Khan had lost a vote of confidence in March 2022, and massive floods submerged large parts of territory in the following summer, with the global energy and food crisis already hitting hard. Drained of foreign exchange reserves that were needed to import foodstuffs and energy resources, the national government had to radically devalue its currency and increase electricity and fuel prices (key IMF conditions), triggering an unprecedented inflation. The currency exchange rate went up from a relatively stable rate of US $1 = 170Rs (Pakistani Rupees) in the years 2019–2021, to 230Rs in 2022 and even reached 280Rs in January and February 2023. Daado shook his head and wearily sipped his tea. Aziz threw a last glimpse at the international news section reporting on the war in Ukraine, when he also shook his head and repeated: “These are hard times, it’s a very bad situation (haalat kharab hai)”. He then told me that he and his family had planned to visit Karachi, Pakistan’s biggest city, to meet friends and relatives, and get some routine medical check-ups in the renowned health facilities there, but the one-way bus ticket alone was 14.000Rs (for a ride of 20-26 hours). Overall, it would have cost them around 4 lakh (400.000Rs) for the whole trip, so they cancelled.

This text looks at practices of negotiating and un-doing inflation in everyday life. While rising prices routinely bring economic hardship for ordinary people, they also open up possibilities to contest the capitalist dynamics that trigger inflation in the first place. I explore this question through two examples: negotiations over the price of tea, and protests against cutting essential wheat flour subsidies. In Aliabad, inflation was far from being a supernatural economic force, and was instead understood as something that was done to the town’s residents by international, national and regional actors. As such, it could also be undone, at least to some extent.

The value of a cup of tea

Later that day, regular customers were scarce, and Aziz had left to prepare his family’s small plot of land for the upcoming seasonal opening of the water channels that Hunza is famous for. Only Farhan and I remained in the tea shop. I asked him whether these days fewer customers were coming because of the inflation. He shook his head: “No, I don’t think so. Not really actually.” I asked him why he kept the price for a cup of tea at 50Rs, given that in other places nearby, prices had gone up to 60Rs and sometimes even 70Rs. “Yes, I know”, he said wearily, then adding defensively “but why should I make my customers worry (parishaan)? For me, it’s okay like that. 50Rs, bas.” A little taken aback, I asked again: “But you also have higher costs, don’t you?” Farhan’s voice grew louder for a second: “Sure, for everything! Milk, tea powder, cooking gas… but 50Rs for a cup of tea is okay. “During the rest of my fieldwork and many months after, Aziz and Farhan stuck to this price, even though both frequently complained of the ingredients’ rising prices. Their refusal to increase the price of tea was an active act of affirming socio-cultural values like sociality, community, and accessibility of chai to customers over merely economic considerations in times of crisis. Whereas many other tea shops in Aliabad were quick to adapt their prices to the inflation rate, Farhan and his father kept it at 50Rs. Notably, these other tea shops were drawing on a different group of (also regular) local customers, mainly neighboring bazaar shop owners, who themself had also increased the prices for their goods and services. Every time I asked Farhan and his father about their reasons for not doing the same, they told me that they don’t want their customers to worry. That way, they emphasized the importance of chai as an essential good that should be provided to their regular customers that were largely older and not very affluent customers (and often neighbors and friends too) who might otherwise not be able to afford it.

Amidst the rapid inflation and unable to postpone the family’s medical trips indefinitely, their rejection of the impulse to raise prices was all the more remarkable. In situations of economic instability, people make price hikes relatable by, for example, complaining or blaming politicians for it (Amri 2023), and frequently – depending on a place’s economic history and imagined future – fall into narratives of despair (Muir 2016). However, such interpretations might overlook how local engagements with inflation are never only passive representations of broader economic developments, but also make for opportunities to actively mediate and navigate the meanings and consequences of inflation. Looking at inflation and price hikes this way means acknowledging that actors can reframe capitalist dynamics, even if they do not make their choices under self-selected circumstances (Narotzky and Besnier 2014; Thompson 1971).

This becomes especially visible when approaching inflation as shifts in the way people value certain things and activities. They thereby engage in “boundary struggles” (Fraser 2022) over, conceptually speaking, the relationships between exchange value and use value – in this instance, of chai. Farhan’s insistence on not changing prices means putting the use value over the exchange value of chai. Use value incorporates here not only tea as something you drink when thirsty, but also its cultural values like facilitating social life, and being affordable to customers. The reasoning behind not wanting to bother their customers is in line with these values of chai in facilitating community and participation in social life. Further, the refusal to increase prices also ensured the continuous coming of customers, and therefore was not entirely contrary to economic considerations.

Given that Aziz and Farhan didn’t make a fortune by their insistence on the 50Rs, their prioritization of social ideals while struggling with rising production costs shows that the relationship between use values and exchange value is never clear-cut nor predetermined. And especially processes like inflation open up avenues for redefining their (albeit fuzzy) boundaries. Adhering to ideas of socio-cultural provision while also ensuring clientele to come, ultimately meant that refusing to play along with the dynamics of global inflation came down to a cup of tea.

Un-doing inflation?

The newspaper that Aziz was reading on that morning in February 2023 also described how the crucial monthly bags of subsidized wheat flour would soon cost 36Rs per kg and might even rise to 58Rs per kg, and not 20Rs anymore. This was not even the first hike. The sub headline read that the rise was condemned by the “Awami Action Committee” that organizes public protests on various issues in the region. For the last few months, the value of the Pakistani Rupee had been decreasing significantly, leading to higher prices for imported oil and gas, among other things. And, it seemed, the regional and national government had decided to translate that price rise into higher prices for flour. When Aziz finished reading, Daado, the older customer next to me, exclaimed: “Listen, this flour subsidy, this is not a gift (tohfa) by the government! It’s our right (qanon), it’s the law of the UN, United Nations!” He said this twice, and with much emphasis.

Over the course of 2023, nation-wide protests against rising costs of living broke out, which the Pakistani sociologist Umair Javed (2023) described as “a product of total frustration at the state for violating its basic obligations towards citizens”. But in Aliabad, many like Daado saw not just a moral obligation on the side of state authorities to care for its people (Thompson 1971), but also a legal one, given the constitutional limbo and the lack of full citizenship rights (such as voting in national elections) of the region due to its relation to the Kashmir conflict (Ali 2019). So, in Gilgit-Baltistan, the rising inequalities, as well as the fact that the government appeared to directly relay inflation and IMF’s austerity measurements into cutting the flour subsidies of the already marginalized region, provided the context for protests against this move. A series of decentralized, often women-led protests and road blocks emerged in summer 2023. And when local state officials made only excuses and empty promises, an enormous, region-wide protest march to the main town Gilgit was organized by the Awami Action Committee that Aziz had read about.

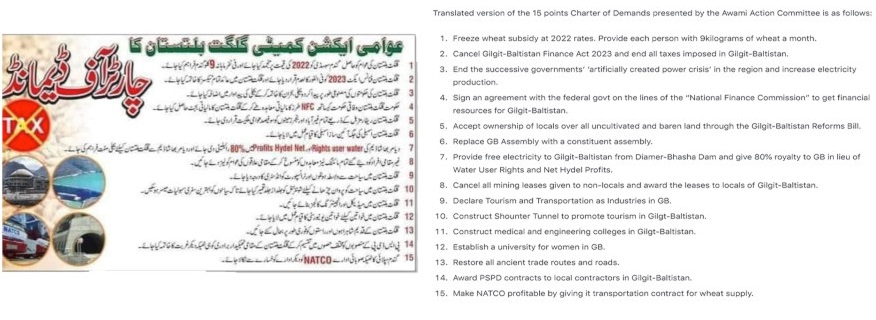

In January and February 2024, huge sit-ins in Gilgit demanded a full reinstatement of the flour subsidy, but also presented a more fundamental 15 Point Charter of Demands. These included constitutional recognition of Gilgit-Baltistan as a full province of Pakistan, protection of communal land rights, a withdrawal of new direct taxes, enhanced transport, medical and energy infrastructure, and improved educational opportunities, especially for women. After weeks of protests (and also briefly before the country’s national elections in February 2024, in which residents of Gilgit-Baltistan tellingly couldn’t even participate), the flour subsidy was reinstated at full rate. The inflation and its impact on the flour rates had mobilized large parts of the population in Gilgit-Baltistan and united them in a broader political struggle. Resisting and even reversing inflation, and through it also forms of political marginalization, suddenly appeared to be possible.

Conclusion

Ethnography allows studying inflation by paying attention to how it is done and undone by various actors with different degrees of power. One avenue for this is looking at how the relationship between exchange and use value is actively re-negotiated. Shop-owners like Farhan and Aziz, for example, did not reproduce inflation in a straight-forward way, and instead prioritized communal values over exchange value. However, given the structural dependency on the cash economy and imports, the question remains how many trips or medical check-ups they can postpone before their refusal to raise the tea price will falter. Equally, the political organizers and the protestors in Gilgit-Baltistan did not agree with inflation leading to subsidy cuts and further deteriorating their economic resources and symbolic recognition in a situation of political marginalization. Their protest actually enabled the lowering of prices, by means of the reinstatement of the flour subsidy.

In their own ways, these two examples represent different facets of how people politicize and seek to un-do inflation. Highly aware of IMF conditions and their peculiar political situation, Aliabad’s residents concerned themselves deeply with inflation and came up with various forms of engaging with it. For my interlocutors, drinking tea and sharing bread with the IMF, then, did not mean falling into despair or normalizing inflation as something given. Instead, they embarked on different ways of politicizing, refusing, and resisting the effects of inflation as an unavoidable part of our economic system.

This text is part of the feature The Social Life of Inflation edited by Sian Lazar, Evan van Roeckel, and Ståle Wig.

Quirin Rieder is a PhD candidate at the Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University Vienna. His doctoral research analyzes how access to electricity shapes social organization in Northern Pakistan.

References

Ali, Nosheen. 2019. Delusional States: Feeling Rule and Development in Pakistan’s Northern Frontier. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Amri, Myriam. 2023. ‘Inflation as Talk, Economy as Feel: Notes Towards an Anthropology of Inflation’. Anthropology of the Middle East 18 (2): 27–45.

Fraser, Nancy. 2022. Cannibal Capitalism: How Our System Is Devouring Democracy, Care, and the Planet – and What We Can Do about It. London: Verso.

Javed, Umair. 2023. ‘Burning Bills’. Dawn, 4 September 2023. https://www.dawn.com/news/1773941/burning-bills.

Muir, Sarah. 2016. ‘On Historical Exhaustion: Argentine Critique in an Era of “Total Corruption”’. Comparative Studies in Society and History 58 (1): 129–58.

Narotzky, Susana, and Niko Besnier. 2014. ‘Crisis, Value, and Hope: Rethinking the Economy: An Introduction’. Current Anthropology 55 (S9): S4–16.

Thompson, E.P. 1971. ‘The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century’. Past & Present, no. 50, 76–136.

Cite as: Rieder, Quirin 2024. “Drinking tea with the IMF: sticking to prices and protesting inflation in Aliabad, Northern Pakistan” Focaalblog 10 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/12/10/quirin-rieder-drinking-tea-with-the-imf-sticking-to-prices-and-protesting-inflation-in-aliabad-northern-pakistan/