One day last October, I happened to spot an acquaintance’s post on Wechat. It was a simple message thanking all ‘Ant-izens’ (people who work in Ant Financial of Alibaba) for their hard work, followed by a short video advertising Ant’s upcoming IPO. It came from a data scientist who had given up his high-paid job in the US, returned to China, and joined Ant Financial three years earlier. Ant shares were then expected to start trading in Hong Kong and Shanghai on 5 November.

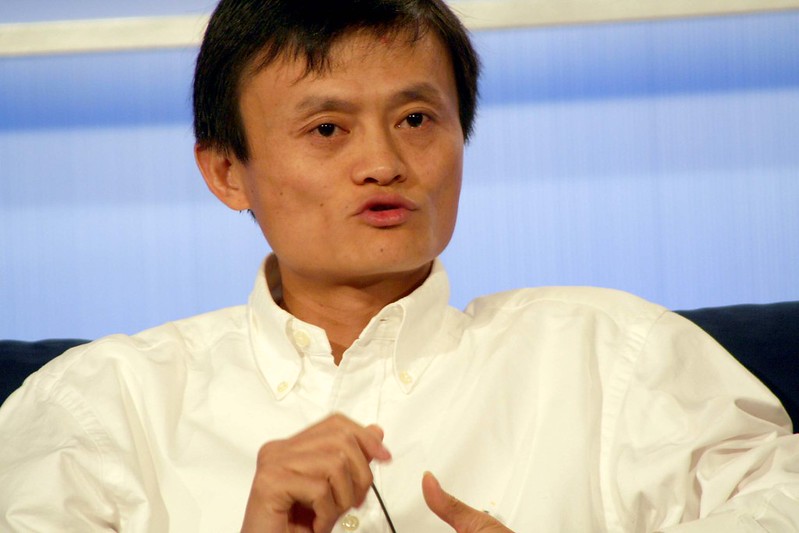

Jack Ma, the founder of Ant and affiliate Alibaba Group Holding, had declared it a “miracle” that such a large listing would take place outside New York. It was poised to raise up to $34.4 billion in the world’s largest stock market debut and would create a vast group of new billionaires. The data scientist’s post, like many posts on social media, was a showoff: it was a subtle public announcement that he was going to become extremely rich in two weeks’ time. The post contributed to a rather complicated, self-consciously suppressed feeling among many professional Chinese Americans: once again they were tasting the bitter feeling of being stuck in the US middle-class, left behind by those who had managed to jump on the fast-track train of China’s economic growth, grabbing opportunity in the mainland and realizing their ‘Chinese Dreams’ by finally becoming ‘financially independent’ (meaning rich enough that you and your offspring would never need to worry about money again).

Then, on 3 November, two days before the feast, the IPO was suddenly called off by the Chinese government. Immediately thereafter, China ordered Ant Group to rectify its businesses and comply with regulatory requirements amid increased scrutiny of monopoly practices in the country’s internet sector. Such a blow! The data scientist kept a dignified silence; my professional friends kept a polite silence. And Jack Ma, the real protagonist of the drama, kept a cautious silence. He has since disappeared from public view (only reappearing on 19 January 2021 with a video emphasizing his social work). Where is he? What is he doing now? What would happen to him? Why would all this happen? What does the state’s intervention mean to Ant and Alibaba, to the whole ecommerce industry, and to the whole private sector? What does it say about the logic of the state apparatus in this enigmatic yet so important country? Where will it go? And how would this affect the rest of the world, especially the West? So many questions and so much drama.

(Source: JD Lasica, https://www.flickr.com/photos/jdlasica/292160777)

Unsurprisingly, the Western liberal media have maintained their usual cold-war tone, by interpreting the drama as a typical attack initiated by a post-socialist authoritarian state towards this too powerful private entrepreneur out of fear or simply for the vanity and narcissism of Your Highness Xi. The Financial Times, for example, compared it immediately with the Khodorkovsky case in Russia (Lewis 2021, paywall). The implication was clear: you can never trust those former socialist authoritarian countries. They would never respect private property, follow the rules of the liberal world, and become “us”. Equally unsurprisingly, some Western Leftists have maintained their idealist tone towards a China that may perhaps be capitalist but is at least not Western capitalist. For them, the crack-down on Ant signifies a determined fight by the state and the population against greedy capital and capitalists.

Most people in China indeed seem to have welcomed the crackdown and support the state’s actions. There are various reasons for such support. One economist I talked to supported it for financial security considerations and for the state’s antitrust efforts. She mentioned the extremely high and hence hazardous financial leverage that Ant Financial is playing with, as well as the antitrust efforts against Facebook and Google in the USA. One private entrepreneur also supported the action for financial security considerations, but based on different reasoning. According to him, since there are many different kinds of capital (including foreign capital) behind Alibaba and Ant, Ant’s IPO would further open the door for foreign finance capital to enter the Chinese market. Some intellectuals talked about the vulgar and disgusting advertisements made by Ant Financial aiming to encourage irrational consumption, as well as the irresponsible private loans it has given out, and how all these behaviors have disrupted social order and degraded social morals.

All these reasons were evident in the government’s statements for halting Ant: to regulate the financial market, enforce antitrust legislation, and create a healthier consumption environment (Yu 2020). This all seems valid except that the role Ant is playing is largely as a platform––a middleman between state banks and individual small-loan borrowers. Much of the capital given out as small loans by Ant actually comes from the state banks. The state banks were not allowed to engage in these high profit businesses. They also do not have access to the necessary consumer data and data science. They normally deal with state owned enterprises. So, Ant stepped in to help state banks exploit a previously untouched financial market: grassroots personal loans. They then divided the profit. As some observers rightly pointed , Ant has always aimed at creating partnerships with big banks, not disrupting or supplanting them. More importantly, quite a few important government-owned funds and institutions are Ant shareholders and were expected to profit handsomely from the public offering (Zhong & Li 2020). Thus, the claim that Ant squeezed out the state banks is spurious. They were basically in the same boat. That is why the state never really regulated Ant before. Meanwhile, we should not forget that the informal financial market has long existed in Chinese grassroots society due to the inaccessibility of bank loans for most non-state economic entities and common people. Ant actually formalized (to a certain degree) this informal market. Yes, Ant did play the financial game of ‘asset-backed securities’ to enhance its financial leverage, but hardly to the extent that Wall Street is used to doing. Finally, what about the irrational consumption encouraged by easily accessible loans (especially for youths)? Maybe. But most such loans still come from other smaller and less responsible lending agencies following in Ant’s steps, which try to grasp crumbs from the huge cake but do not have the technology and data required to avoid excessive risk. It is these smaller and less technologically capable actors that are in fact creating chaos in credit supply. In short: even if we all agree that financial capital has always been highly speculative, and that Ant is no exception, some of the official statements justifying the intervention into Ant’s IPO still sound fishy.

Meanwhile, the poor in China still seem the most determined supporters of the state’s crackdown on Ant. They supported it out of their hatred toward big capital. On the internet, they lambasted the bloodsucking behavior of Ant, and called it “Leech Financial” instead of Ant Financial (Leech is pronounced in Chinese as “Ma Huang” and ant is pronounced as “Ma Yi”). There is also a popular cartoon being circulated on the internet that depicts Jack Ma as a beggar in his old age—homeless, fragile, and sad. One blue-collar worker told me that any big capitalist whose main objective is to extract money from the poor should be dragged down.

Tellingly, the state has intentionally toned down popular indignation. The relationship between state and capital in this country has always been much more complicated than the mere antagonism imagined by liberal commentators. The state can’t afford a strong group of capitalists with too much power and resources; but neither can it afford losing them and scaring capital away. It has always been an art of balancing. As we have seen, Jack Ma has reappeared recently with a more solemn appearance. His Ant is now required to deploy necessary ‘rectifications’ under the tighter rein of state regulation (CBNEditor 2021). It is, nevertheless, the right thing for the state to do, no matter the underlying aims. Ma, of course, should always keep in mind that there has never been an Era of Jack Ma; it has always been the Chinese Era that created him, as one Chinese official newspaper publicly warned him as early as 2019.

As for those professional Chinese Americans who believe that they have missed the recent gold-digging opportunities in China and have started to doubt their earlier decision to go abroad, the crackdown on Ant—or more specifically, the broken dream of becoming a billionaire data scientist—has taught them a rather comforting lesson: miracles, whether for a country, a company, or an individual, are slippery. A boring yet relatively predictable middle-class suburban life in the West should at least be bearable, perhaps even enviable.

Juzimu is an ethnographic researcher of Chinese capitalist transitions and writes here under pseudonym.

Bibliography

Lewis, Leo, “What we can read into Jack Ma’s disappearance: Printed speech holds key to Alibaba founder’s invisibility — and rehabilitation”, Financial Times, January 8, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/b3a94f55-5e44-417f-a869-a542d0527fe7

Yu, Chao, “Anti-Trust Rugulation is for Better Development,” Renmin Daily, Demember 25, 2020. http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2020-12/25/nw.D110000renmrb_20201225_3-07.htm

Zhong, Raymond & Cao Li, “Ant Challenged Beijing and Prospered. Now It Toes the Line.” The New York Times, Oct. 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/26/technology/ant-group-ipo-china.html?_ga=2.55348649.308985693.1613408960-1859810252.1601304805

CBNEditor, “Ant Group Has Established Rectification Team for Business Overhaul: Chinese Central Bank”, January 18, 2021, China Banking News, https://www.chinabankingnews.com/2021/01/18/ant-group-has-established-rectification-team-for-business-overhaul-chinese-central-bank/

“There Has Never Been an Era of Ma Yun; It Has Always Been the Chinese Era That Created Ma Yun,” People’s Financial Comments, September, 17, 2019.

Cite as: Juzima. 2021. “Jack Ma: Wherever the Wind Blows.” FocaalBlog, 8 March. https://www.focaalblog.com/2021/03/08/juzimu-jack-ma-wherever-the-wind-blows/