The election of Javier Milei, a chainsaw-wielding anarcho-libertarian, to the Presidency of Argentina promises to cement Argentina’s status as a prime experimental site for inflation-tackling policies; it also highlights how experiences of inflation can prompt electorates to turn to radical political alternatives. The country has a long history of inflationary crisis, dating back to the 1970s, with the worst episode occurring in 1989 when hyperinflation led to an annual rate of 5 digits. Argentina has changed its legal tender 4 times since the 1980s as a response to inflationary tendencies and the US dollar has become increasingly important for the economic lives of ordinary people (Luzzi and Wilkis 2023). So much so that the market for real estate has been in dollars since the 1970s and some estimate that 2 out of 10 US dollars in circulation outside of the United States are in Argentina, 10 per cent of the total amount of dollars in use worldwide.

By October 2023, a crucial time in the presidential election campaign, annual inflation had reached 140 per cent. News reports described daily price markups in supermarkets and increasing volumes of products being left at the till (an indication of the difficulties customers had in estimating the purchasing power of their money). The US dollar had more than 15 different exchange rates (official and unofficial, for different commodities, credit cards, tourist rates, and so on) and the government capped the number of dollars that could be legally purchased each month, in an attempt to prevent the continuous diminishing of national reserves, deeply affecting people’s capacity to save in the only stable store of value they trust.

Most striking was the way that inflation, its alleged causes, and proposed solutions dominated public debate and every political party’s platform. But it was Milei who came through with the most extreme discourse, declaring that he would tackle what he defined as a ‘monstrous monetary disarray’ (Milei 2023) by dollarizing the economy and closing down the Central Bank. His rhetoric worked, and although as President he has subsequently been forced to backtrack on a number of his early propositions, including dollarization, he has not held back from what feels to many Argentines like a painful, extreme, and tragic adjustment in their economy and polity. His government has fired over 26,000 public sector workers, kept higher education budgets stable, and refused to increase salaries and pensions even though inflation remains stubbornly high, at a 271 per cent annual rate in June 2024. His focus on ‘deficit zero’ is a classic monetarist recipe for managing inflation and the state, and the IMF and foreign exchange markets seem reasonably content – although they haven’t (yet) given him any actual money.

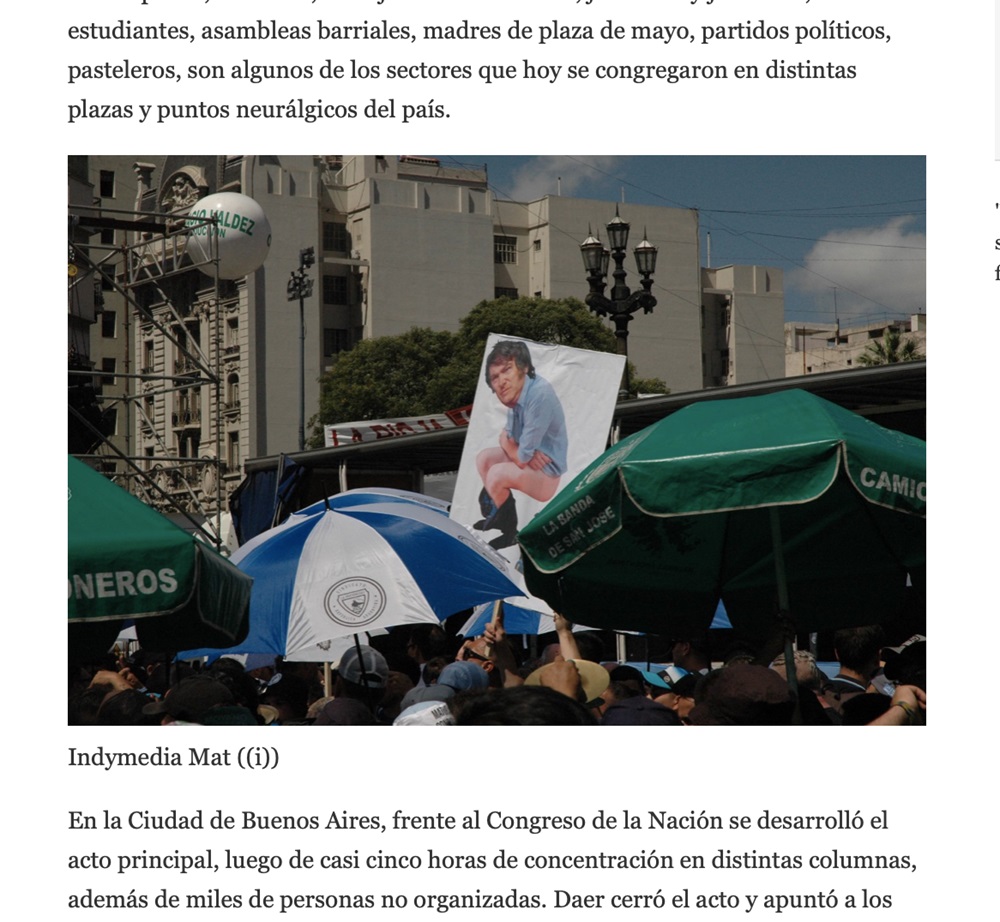

Meanwhile, in the first half of 2024, poverty levels increased to over 50 per cent, with extreme poverty (‘indigencia’) at about 18 per cent, both significant increases since Milei assumed power. People of all classes have dampened down their everyday consumption, and many are very worried indeed about how they will reach the end of the month. September 2024 saw some early signs of the dollar stabilizing, even going down against the peso (from a high of about 1500 pesos per ‘dólar blue’ illegal rate a few months ago to about 1210 pesos at the end of September). Prices don’t appear to have reduced in the same timeframe, though. And many remain fearful of losing their job. Demonstrators, including pensioners, who protested the government’s refusal to bring the state pension up by an additional 8.1 per cent were tear-gassed, and university teachers and students are mobilizing to demand sufficient budget to keep buildings open and salaries enough to live on.

Milei does not seem to care too much about the opposition on the streets: university scientists are, he says, members of ‘la casta’ (the political caste), the political establishment that he railed against as a candidate and continues to stigmatize as morally corrupt. Meanwhile, the 87 Congress deputies who voted against the rise in state pensions celebrated with a barbeque at the Presidential residence. The push and pull of a Congress majority that seeks to overturn or blunt the effects of his austerity decrees, street level mobilization (and repression of that mobilization), and continually wild rhetoric from the President is making for a hugely complex and quite inflammable political situation. The need to address inflation has opened up rhetorical and political space for an extreme version of neoliberalism, and at this point we can’t tell where that will end up. If it is successful in bringing down inflation, it will be evident to policymakers elsewhere that monetarist policies can work (to that end at least) but also that they bring with them a significant social cost.

The Return of the 1990s

The situation of painful inflation in 2023 opened voters’ minds to a very colorful character. On a number of occasions during the campaign Milei delivered speeches holding a chainsaw with which he said he would destroy the Central Bank and eliminate ‘la casta’. His followers produced cardboard versions of the chainsaw to wield at rallies (Vásquez 2023). He has described himself as a libertarian and an anarcho-capitalist, and aligns himself with extreme market fundamentalism. He admires Donald Trump and Margaret Thatcher and named his cloned English mastiffs after the US libertarian thinkers Murray Rothbard, Milton Friedman, and Robert Lucas. According to some news commentators, he discusses economic policy with his dogs. His speeches during the campaign and since are brash and – to many – vulgar, for example when he recently made an offensive gesture with his right hand during a speech about reducing public expenditure. Not everyone feels the same way about him, though. Depending on who you talk to, he’s an embarrassment, a disaster, a breath of fresh air, or a response to really fundamental exhaustion with business as usual. To many, it is very appealing that he sets himself aside rhetorically from the political establishment.

Yet, Milei’s self-fashioning as a charismatic leader is also based on an aesthetic and narrative citation of the figure of Carlos Menem, President from 1989 to 1999. One of Milei’s early acts as President was inaugurating a bust of Menem in the presidential palace with the presence of his daughter, Zulemita, as a front row guest at the official ceremony; he has described Menem as ‘the best president in the history of the country’. Milei even has a similar hairstyle to Menem, a kind of visual intertextuality (Lazar 2015) that we should not overlook from this most symbolically-conscious of political actors. That all matters because of Menem’s relation to earlier periods of inflation. Menem is the main figure associated with neoliberal small-state ideologies and their implementation in Argentina, the ‘strong man’ who controlled the hyperinflation of 1989-1990 through an exercise of neoliberal shock therapy celebrated by the IMF as one of the most drastic in the world. Together with his Minister of the Economy, Domingo Cavallo, he brought both economic stability (via the Convertibility Plan that kept the peso at a 1:1 exchange rate with the US dollar during the 1990s) and its subsequent collapse, in one of the most acute economic crises the world has seen this century (in 2001). By associating himself with Menem, Milei is making the claim that he will be similarly successful; that his economic policies will usher in a similar period of stability and consumption. He is quiet on the subsequent collapse, of course, but that remains at the forefront of his opponents’ minds.

Terminator in Office

The invocation of the 1990s is combined also with a claim to novelty, to breaking with past assumptions, especially about the role of the state. In his first speech as president in December 2023, Milei addressed Congress and the population stating that it was the beginning of ‘a new era in Argentina’. Symbolically, he did not deliver the speech inside the Congress, but rather outside and turning his back on it. After the official speech, he addressed his supporters more directly, saying something that has by now become his trademark: ‘There is no money’. He added: ‘There is no alternative to adjustment and shock’ to the loud cheers of thousands of supporters.

But, despite the emphasis on a radical new approach in terms of the political responses to the crisis, non-linear continuities with the past also became noticeable. And while in rhetoric Milei condemned ‘la casta’, many prominent political figures from the past populate government ranks, including several members of the Menem family –or ‘Menem clan’ as journalist Gabriela Vulcano described them – who were given important political positions.

More important to the way Milei has addressed inflation are the leading economists in his team. Federico Sturzenegger and Luis ‘Toto’ Caputo were both key figures in economic policy-making (both presidents of the Central Bank) during Mauricio Macri’s administration (2015-19) and they are now both Ministers (of Deregulation and the Economy, respectively). In their hands, monetary policy has been focused on reducing the deficit and reaching ‘fiscal order’, terms that are supposed to ‘stabilize’ the economy. Milei also emphasizes privatization as a flagship policy, with arguments that could have come directly out of the early 1990s: that public companies drive deficits, drain public funds, and provide bad services. In a TV interview shortly after winning the elections, he claimed: ‘Everything that can be transferred to the private sector, it is best that it is in the hands of the private sector (…) Because it has been proven that everything that the public sector does, it does badly’. That said, while Menem had been swift in selling state assets and companies, Milei is having less success and experiencing far more opposition to those particular measures. To this day, no sales have actually been agreed.

It’s not clear how far Milei and his allies will be able to proceed in their goal of reducing the state as far as possible to its security apparatus and that which is needed to promote their own electoral goals (a strategy familiar to politicians well beyond just Menem and Milei). The debate has moved slightly on from inflation per se into a broader attack on the very concept of state care and of the public. In an interview given to the US media outlet The Free Press, Milei claimed that he would ‘destroy the state from within’ and compared himself to the sci-fi character Terminator who comes from an ‘apocalyptic future to prevent the advance of socialism’. This destruction is underway through a constant attack on the notion of the ‘public’ and the workers who bring it to life as de facto socialist and therefore evil. It’s a more aggressive version of the attitude revealed in the 1990s comedian Antonio Gasalla’s affectionate caricature of the ‘empleada pública’ (state employee) who extracts a bribe, exerts her authority, and sips mate while citizens queue up outside her office to put through a tramite (bureaucratic task), only for the piece of paper they bring to be ripped up and thrown into the trash once they turn their backs, while their 100 pesos is carefully pocketed.

While Menem could reduce the fiscal deficit by moving national state expenditure on health and education to provincial budgets, Milei has less room for maneuver. A number of the people around him are instead promoting a more familiar transfer of resources from the middle/lower-middle classes to elites, via taxation concessions. His attempts to block labor rights are currently stalled due to a legal case brought by the General Trade Union Confederation (CGT), and his government’s refusal to meet its legal obligation to provide food for communal kitchens is also being challenged in the courts, with judge after judge ruling against the government. Not many are optimistic about the chances of inhibiting Milei’s worst excesses, but those who are optimistic point to the Legislature elections coming up next year, which might reduce his political legitimacy. Yet, it’s the attack on the state – and on public sector workers and politicians in particular – from which Milei derives much of his popular legitimacy, and it’s that which sounds so familiar to the debates about adjustment and privatization of the 1990s. It is a long-embedded way to understand politics and the state, but even that probably won’t last much longer into the future if prices continue to rise.

This text is part of the feature The Social Life of Inflation edited by Sian Lazar, Evan van Roeckel, and Ståle Wig.

Sian Lazar is Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. Her latest book is How we Struggle: A Political Anthropology of Labour (Pluto Press).

Dolores Señorans is Departmental Lecturer at the Oxford Department of International Development. Her research focuses on popular economies and collective labour politics in Argentina.

References

Lazar, S. (2015). ‘“This Is Not a Parade, It’s a Protest March”: Intertextuality, Citation, and Political Action on the Streets of Bolivia and Argentina.’ American Anthropologist, 117: 242-256.

Luzzi, M., & Wilkis, A. (2023). Dollar: How the US Dollar Became a Popular Currency in Argentina (1930-2019). University of New Mexico Press

Milei, J. (2023). El fin de la inflación. Eliminar el Banco Central, terminar con la estafa del impuesto inflacionario y volver a ser un país en serio.Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Planeta.

Vázquez, M (2023) ‘Los picantes del liberalismo. Jovenes militantes de Milei y ‘nuevas derechas’’’; in Semán, P. (ed) Está entre Nosotros. ¿De dónde sale y hasta dónde puede llegar la extrema derecha que no vimos venir?. Buenos Aires: siglo veintiuno

Cite as: Lazar, Sian and Señorans, Dolores 2024. “Argentina: inflation, monetary disorder, and political experimentation” Focaalblog 10 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/12/10/sian-lazar-and-dolores-senorans-argentina-inflation-monetary-disorder-and-political-experimentation/