In October 2023, I sat with Hameed in a café in Hamra in Beirut, nearby his flat. He had just collected his salary, a stack of green 100,000 notes of Lebanese lira that amounted to 12 million (around 130 dollars): “look,” he said despondently, “this is not going to last more than two weeks, the company are thieves.” I asked him how he would survive. Rather than saying out loud, he preceded to sheepishly get his phone out and start typing on the calculator how much money he owed to friends, 42 dollars, 38 dollars, 180 dollars, 72 dollars, he kept going. It came to 500 dollars, but these were only the amounts he remembered at the time.

Hameed had come to Beirut from Syria with his family in 2011, after the civil war broke out. He had worked multiple jobs, without a work or residence permit, in Beirut’s service economy. For the last 3 years he had worked as a driver for the Lebanese food delivery app Toters. Toters has grown rapidly in Lebanon in recent years. Its rise has been stimulated by the multiple crises that have crippled the Lebanese economy: the financial crisis of 2019 and subsequent economic downturn led to its competition exiting the market; the Covid-19 pandemic dramatically increased home delivery; and the Syrian war provided an army of cheap, undocumented Syrian labour.

The financial crisis has had other consequences. One has been the dramatic surge in Lebanon’s cash economy, which went from 14 per cent of GDP in 2020 to 46 per cent in 2022. This has rapidly produced a new set of infrastructures, actors, and practices for storing and circulating money – at a time of rapid currency devaluation and increased dollarization. Companies began operating in cash due to exorbitant bank fees and distrust, money transfer and exchange services with links to political parties have boomed, and new digital wallets (like the company Purpl) are trying to fill the void left by banks.

When I was following the lives of Syrian drivers working for Toters between January and October 2023, I became interested in the ways in which cash was moving around the mini-economy created by Toters, between customers, delivery drivers, team leaders, money storers, and the company itself. What I want to argue is that, by following cash around, we can see how infrastructures of money circulation become a terrain of struggle between different actors (Scott, 2022). In this instance, the circulation of cash became a way for Toters to extract extra value from its racialised workforce and customers. But it also opens up the possibility for fractured forms of resistance and survival for workers.

Theft through depreciation

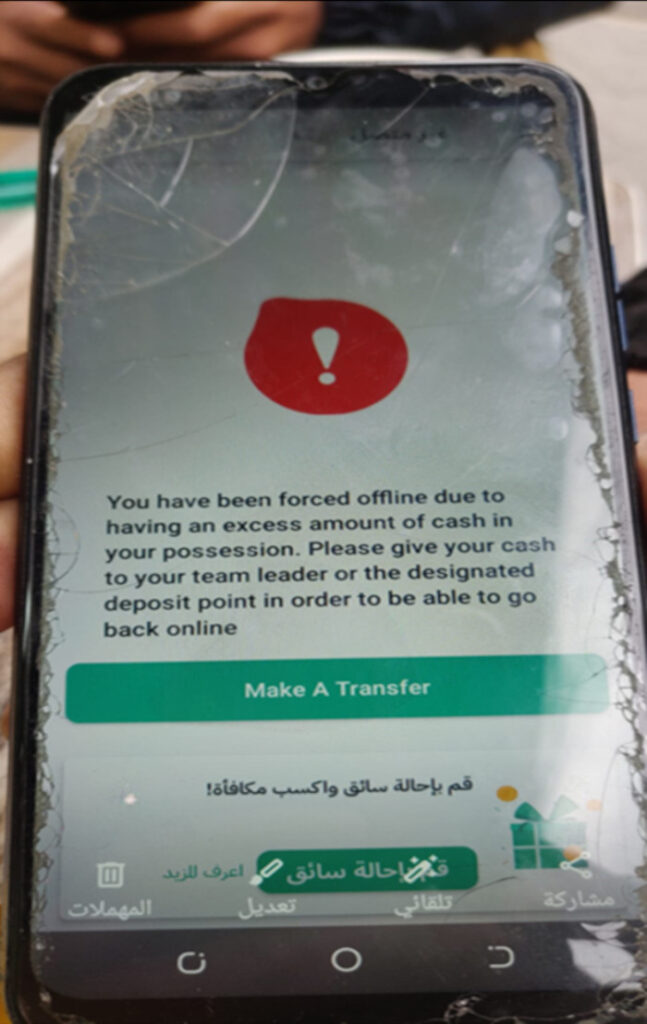

Between January and April 2023, the value of the Lebanese lira plummeted. It lost 61 per cent of its value to the dollar. Customers ordering food on Toters had to pay in lira – although sometimes drivers accepted dollars and exchanged it themselves for a small extra fee, without the company’s knowledge. Customers paid in cash directly to the drivers as they delivered orders. When a driver collected three million lira, their account was automatically blocked and they could no longer take orders. To reopen it, they had to go to their team leader who waited at the same spot every day to deposit the money, or use BoB, a Lebanese money storage and transfer depository. This took time away from doing more orders. Any missing money – due to theft or miscalculation – always had to be made up by the driver. Once in BoB, this money was converted into dollars and transferred to a bank account in Dubai where Toters’ official headquarters is located.

By doing this, Toters was able to protect itself from the currency devaluation of the lira. However, this was not the case for drivers. Drivers received a basic fee for each order, plus an extra fee based on distance. In addition, when fewer drivers were on the road, delivery competitions were organised by the company: e.g., if a driver did six orders in two hours, they got an additional amount. On a day of no interruptions drivers did 20-25 orders, which produced ten to twelve dollars (500,000-600,000 Lebanese lira) in earnings. The fees were accumulated, recorded on the mobile app and distributed to drivers in Lebanese lira at the end of each month. This delay meant they had to watch helplessly as the value of their labour plummeted over the month – for example in January 2023 drivers lost a third of the value of their earnings. Meanwhile, their expenses such as rent, electricity, internet, food, and petrol were either paid in dollars or went up with the dollar very quickly.

For Hameed, this induced much frustration, as he described while we sat in a café in mid-March 2023:

“I’m tired, I’m tired. The dollar reached 100,000 lira today, it will reach 200,000 as well. [He pointed to his pack of cigarettes] look, 50,000, the coffee 40,000, then petrol is now 400,000 a day, you spend 600,000 easily, and you don’t even make that from orders. I don’t understand why all the expenses like rent and electricity, even coffee goes up straight away when the dollar goes up, but the only thing that doesn’t go up is the salary. The company just makes extra money, the restaurants can raise their prices, but the workers paid in lira are just losing.”

This depreciation was also a problem for restaurants, who had to wait two weeks before getting their revenue from Toters, which at times led to a 20-30 per cent devaluation of the money. As one restaurant owner told me: “[Toters] are worse than Riad Salameh (the former Lebanese Central Bank Governor), all this playing with money, they have an amazing cash flow…you know they told me ‘we are partners’, I said you are my partner in profit only.”

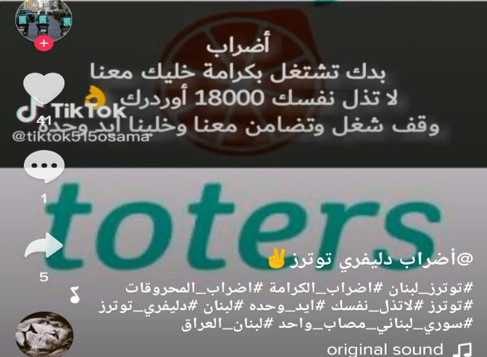

The way in which cash circulation was set up enabled Toters to extract extra value from the drivers and the restaurants. As Hameed mentioned, restaurants were at least able to raise their prices or start pricing in dollars. The organisation of a percentage fee between 20-25 per cent – with the restaurant paying the costs of VAT and discounts – ensured the platform’s income went up automatically. To keep pace with lira devaluation, drivers’ order fees would have had to increase by 155 per cent between January and April. However, for the month of January the fee did not change despite drivers’ complaints. Drivers demanded their salaries and fees be calculated in dollars. At the end of January, they organised a two-day strike through WhatsApp groups, word of mouth, and TikTok. While impossible to know the scale exactly, at its height 900 people were in the main WhatsApp group, and the Toters app was effectively shut down.

Toters tried to break the strike by punitively firing strike organisers and by sending messages telling drivers they had to do a minimum amount of orders or face firing. But eventually, as Toters’ reputation took a hit on critical media channels, it gave a 38 per cent increase in lira with very modest increases following later as the lira continued to rise. However, to compensate, Toters used its digital infrastructure to rapidly increase the delivery fee charged to customers, the vast majority of which went to the platform. Drivers complained that this had the cruel effect of suppressing tips as customers considered the fee the tip. Furthermore, after the order fee increase, for a while Toters stopped organising competitions for additional income, thus further suppressing driver wages.

Borrowing cash to survive

Amidst devaluing incomes, drivers were constantly pushed into situations where they could not pay expenses. Monthly incomes never reached more than 200 dollars, and were more often around 120-160 dollars. This was just about enough to afford food and rent – but the sickness of a child, a broken or stolen motorbike, or an issue at home, as one driver described, would easily break the delicate balance they were living with. One of the biggest issues they faced were the checkpoints set up by the ‘darak’ (Lebanese internal security forces) which, according to drivers, particularly targeted Toters workers because they were known to be undocumented Syrians – thus making them an easy target for bribes. Officers asked for a work permit, then confiscated the bike, which was only reclaimable upon payment of a fine – anything between 10 and 50 dollars.

In this context, drivers needed to constantly borrow money to sustain their livelihood. I was introduced to this situation when I met Hameed in late-February after his account had been closed. I accompanied him to an online gaming shop. He went up to the man at the desk and took 900,000 lira (15 dollars at the time). Hameed then went straight to the coffee shop across the street where his team leader was waiting and handed over 3 million lira. When he came out, he explained how he had taken money collected from the customers to buy a new gas canister. He therefore needed to borrow from his friend to return the money to his team leader. After getting his account reopened, he would work for an hour and then pay his friend back, again from the customer’s money. When I responded in shock, Hameed shrugged and said: “one borrows from another and then one borrows from another, the money just goes around. That’s how it is here” (this is similar to the circulation of debt found by Isabelle Guérin (2014) in South India).

It was very common for drivers to use the cash from customers to pay for both daily expenses and emergencies. The salary disappeared quickly on rent, electricity costs, and food, while tips were highly unpredictable. As a result, the customer money was an immediate source of cash. If depositing this money in a money transfer service such as BoB, drivers would not have to return the whole amount they owed, just make sure they remained beneath the threshold of three million.

While team leaders were also there to collect customer cash for the company, they sometimes helped drivers out. This could be through raising their cash threshold, or reopening their account, but it also included more personal practices. One described such an occasion to me: “one of my drivers hurt his leg, and needed a gel. He came and gave me the customer’s money, but said he can’t work. I asked why he didn’t buy the gel, he said he has no money. So I gave him 250,000 from my personal money.” This team leader described how his positionality helped him act in this way: “management just think the drivers lie, but I know what they go through, so I can help them out. This was a friend situation, not a work situation, in work I am professional. I understand the company can’t become soft, drivers do lie, they can’t give exceptions to people.”

This practice of survival is directly enabled by the fact that money circulation took the cash form. Another delivery company actually formalised this practice of borrowing by lending money directly to drivers, but taking collateral such as a car, bike, or piece of jewellery in case they did not repay, and deducting directly from future salaries. But borrowing from Toters was not enough to meet monetary needs. On some occasions I heard about drivers who had stolen money from the company when they had just collected a huge order. These drivers earned heroic status among others. However, it was extremely risky as the company could mobilise their close connections with the police to locate drivers. For the most part, drivers relied on a network of communal support. This reflects what others have found especially in communities where formalised banking is not preferred (Wig, 2023). This took multiple forms, from borrowing electricity, internet, or food from neighbours, taking products from shops and paying back later, or borrowing small amounts from friends and other drivers. But it also took the form of taking larger amounts of several hundred or thousands of dollars – often from a relative abroad or a driver who had no dependents.

Drivers were therefore always in the process of paying someone back. Sometimes lenders were flexible because they were family or long-term friends. But this flexibility was precarious and open to sudden change. For Alaa, a 21-year-old driver who carried financial responsibility for his whole family, this veneer of stability was lost when several events occurred at the same time. It began with a bike accident that left him unable to work. This meant he was unable to pay the rent. Soon after the man from whom he had borrowed to buy his motorbike demanded repayment. To avoid the threat of arrest or violence, Ahmed gave the bike back until he could find the 500 dollars required. During this period, Ahmed complained about how Lebanon’s economic crisis was reducing generosity: “people are holding on tighter to their money nowadays”, he lamented. Eventually he did manage to scrape together the cash needed, only to quickly meet another request for money; this time from the police regarding a bike he had sold two years before but was still registered in his name – which had now accumulated various fines.

Conclusion

The stories described here demonstrate the vastly different means different actors have to control the circulation of cash. In a context of rapid inflation and currency devaluation, Toters was able to arrange this circulation in a way that enabled them to extract extra value from drivers and customers. They used temporal techniques and flexible digital infrastructures to control the flow of cash to their benefit. To counter this, the undocumented Syrian drivers had little room for manoeuvre – other than risky, arduous tactics such as borrowing, theft, and collective action. Instead, their liveability, and therefore the extractive operation of the company, relied on material and social networks of communal support to acquire the cash they needed.

This text is part of the feature The Social Life of Inflation edited by Sian Lazar, Evan van Roeckel, and Ståle Wig.

Harry Pettit is an Assistant Professor in Economic Geography at Radboud University Nijmegen. He is interested in researching the new forms of extraction and livability opening up within late-capitalist systems, with a focus on the MENA region.

References

Guérin, I. 2014. ‘Juggling with Debt, Social Ties, and Values: The Everyday Use of Microcredit in Rural South India.’ Current Anthropology, 55 (9), pp. 40-50.

Scott, B. 2022. Cloudmoney: Cash, Cards, Crypto, and the War for Our Wallets. New York: Penguin.

Wig, S. 2023. ‘Infrabanking: Mobilizing capital in communist Cuba.’ Economic Anthropology 11 (1)l, pp. 59-70.

Cite as: Pettit, Harry 2024. “Theft, resistance, and the struggle over cash circulation in Beirut’s platform economy” Focaalblog 10 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/12/10/harry-pettit-theft-resistance-and-the-struggle-over-cash-circulation-in-beiruts-platform-economy/