Zavaleta: “[Apparent states] appear to be Western… in all respects but somehow they are not. What misfires here is a structural concept of sovereignty that is ultimately incompatible with the condition of non-centrality in the world, at least in history such as it has occurred until now…. They have only a vague sense of self-certainty, that is identity. We can therefore also call them uncertain states.” (2018: 69 Itals mine)

In the 28 January issue of Viento Sur Pepe Mejia writes, “The dismissal of [Peruvian President] Pedro Castillo, on 7 December, was the starting signal for the organization and celebration of mobilizations that began in Puno, a territory rich in lithium and uranium and the target of large extractive companies.” (Mejia, 2023) He goes on to provide a concise summary of the situation in Peru and sets it within a brief history of the relationship between the rural people of the Andes and the Lima pitucracia on the one hand and the contracts with foreign-owned extractivist corporations that go back to the guano era on the other.[1] By contrast, in an article by Tom Phillips in the Observer two months after the outbreak of events, headed ‘My city is destroying itself’: Juliaca under siege as death toll rises in Peru’s uprising, a kind of crazed self-destruction is described as victims of ‘corruption’ burn tires and the military holes up at the airport. There’s no discussion of Peru’s history, no exposure of the contracts Mejia mentions nor the least attempt to explain to the unfamiliar reader why the re-writing of Peru’s constitution is a central demand of these people.

On the other hand, perhaps the reason the established press writes so little about Latin America’s fourth largest nation is because Peru, as such, does not really exist. Writing about Bolivia and Peru’s war with Chile from 1879 to 1884, Rene Zavaleta Mercado, ‘the Bolivian Gramsci’ as he was sometimes called, ascribed Chile’s victory to the failure of its allied adversaries to constitute coherent states, the ‘integral state’ to which Gramsci had referred. For Zavaleta the effect of the war was to produce for Chile what he called a ‘constitutive moment’ the elusive essence that may or may not bring forth a coherent national social formation, “something potent enough to interpolate an entire people….it must bring forth a replacement of beliefs, a universal substitution of loyalties, in short, a new horizon of visibility.” ([1986] 2018: 75). His historical method was to seek to identify such moments their momentary success and, so often, the failure of their promise.

For Peru it may be that there has never been such a constitutive moment, elusive, temporary or otherwise. Writing of the hundred years following the war the economists Thorp and Bertram subtitle their book, Peru 1890-1970 (1978) ‘an open economy’. It was a society controlled from Lima that was open for business and closed for the ninety-percent of its citizens living in the Andes or their kin struggling in the shanty towns of the capital. In the strictest sense, in the Durkheimian sense, it wasn’t even a society. Perhaps it still isn’t. Writing a quarter century after Thorp and Bertram Debbie Poole and Gerardo Renique (2003) referred to it as “the privatized state.” And here we are twenty years later with Peru scarcely ever mentioned in the European or North American press and when it is the treatment is superficial and pathetic, an ignorance of history and a kind of willful refusal to ask the kinds of questions one would need to know about an open economy and a state so privatized as to be incoherent.

Dismissing Castillo to renew the ‘surplus without a state’

Apparently, the rural working people of Peru and their kin and comunaros/as living in Lima’s shanty towns are unhappy with the school-teacher president they elected, Pedro Castillo, being declared a traitor and thrown in prison by the Congress. Why? Is there some history that might help us to understand – even quite recent history like the fact that the President of the distrusted Congress that impeached Castillo is José Daniel Williams Zapata, an ex-army general who at the rank of colonel was involved in the massacre of 61 people (23 of them children) in Accomarca back in 1985? Or still more recently, the fact that the constitution for which they want the same kind of re-working that got so much attention in the western press when it occurred in Chile, is the one Fujimori, like Pinochet before him, produced to give legal form to his authoritarian neo-liberal regime.

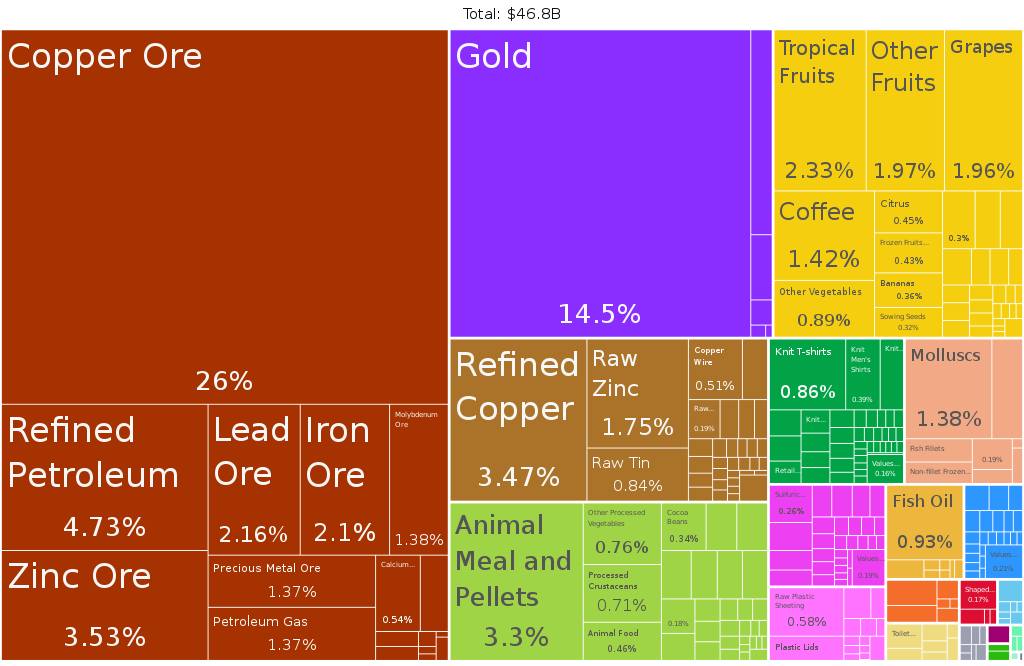

Meanwhile in a country so entirely open to foreign privatized interests surely more useful for the inquisitive reader than the burning of tires and the frying of a cop in his car, is the fact that 2023-24 will be the period when a vast array of the contracts Fujimori signed with foreign companies will come up, not just the extractive ones in oil, gas, copper, lithium etc. but the banks and hedge funds that financed them. There are more than 900 contracts up for renewal. Could this be newsworthy for the likes of the Observer and other western media? Apparently not. Yet, speaking of the proposed renewal of these contracts Mejia notes in the above-cited reporting from Viento Sur, “The term of the contract is generally 30 to 40 years and no one can change the term. This contract law cannot be modified for any reason. Nor can it be modified even if the people go on strike or the congressmen want to annul it.” He adds that in these contracts the ratio of the profits retained in the country to those exported is 18:82 (Mejia, 2023)

Zavaleta spoke of “Peru, the paragon of a surplus without a state.” (2018: 71) Reflecting on the elusive ‘abstract state’ that momentarily may achieve a kind of coherence in a conjunctural moment, a bedrock that might give character to subsequent national projects, Zavaleta spoke of the ‘fruitfulness’ of the surplus to produce a constitutive moment. Among other things sterility results from two factors: the inability to produce coherence when such vast amounts of surplus value are being sucked out of the social formation; and the distributive failures by the national bourgeoisie of what little is left (Zavaleta, 2018; see also Marini, 1981, 2011). Is it then possible that it is not Peru that is ’uprising’ but a variety of regions of Peru each having to deal with its own particularities: a past made up of histories of distinctive struggles not as yet combined nationally; and a present characterized by the distinct contracts each has with the capitalist firms extracting local resources be it the decades old experience with copper in the central Andes or the incubating ones around lithium in the south.

I want to put meat on the bones of such a suggestion by first describing a period I am familiar with in the central Andes when, in Zavaleta’s terms Peru failed to produce a constitutive moment, and then provide brief descriptions of the kinds of contracts that are so determinant of regional conditions from one part of the country to another.

Criollos and Montoneros

Let me turn back to that failed ‘constituent moment’ for Peru during the Pacific War of 1879 to 1884 with Chile that Zavaleta spoke of. Lima, that is to say ‘Peru’ fell ignominiously soon after the war began. But when General Caceres retreated into the central highlands a different kind of war ensued. (Manrique, 1981) Apart from anything else just who was fighting whom. On arrival in the Mantaro Valley it was in part through the influence of his cousin the hacendada Bernarda Pielago that he was able to raise a force of guerrilleros from among the pastoralists that worked in and around her properties in the highlands. In those initial days the emerging montoneros referred to Caceres as taita (familiar term: uncle); by the end, in response to a demand that they descend to the valley to report to the general, their leader sent the message, “Tell Caceres I am as much a general as he is and will be dealt with equal to equal.”[2] It’s the kind of story so familiar throughout Peruvian history, one to repeat itself again and again. Speaking of the Pacific War in the highlands in 1989 I wrote, “The war thus gave birth to a fatal combination – a self-confident peasantry and an expansionist landlord.” (Smith, 1989: 67)

Plus ça change: in the context of what we read about today, it sounds familiar: a situation in which expansionist landlords perhaps have been replaced by expansionist extractive companies. As the following paragraph makes clear it was for the highland people of the central region ‘a constitutive moment’.

[As the war wound down] the montoneros, once mobilized, remained so. But the composition of their enemy shifted. At the beginning of hostilities these montoneros were fighting the foreign invaders; at the end they fought alone against a wide range of opponents – landlords, the commercial classes of the valley, and the agents of the state [especially Caceres]. Such an experience made a profound impression on their culture of opposition, colouring their attitude toward political confrontation for the century that followed. (ibid:68)[3]

Nevertheless, the ability to divide and conquer saw the end of that moment then, as perhaps today too.

Yet in a sense the period of the montoneros has the elements of a constituent moment for the highland regions of the central Andes. When Mejia remarks of Peru’s Andean people, “No necesitan tener un título para salir a la calle y conseguir sus reivindicaciones,” he is alluding to the many times when rural people have resisted by simply occupying space: “They don’t need title deeds to go to the streets and recuperate what belongs to them.[4]” In 1948 the Huasicanchinos of the central highlands faced off against the army to occupy the lands of Hacienda Tucle and Hacienda Rio de le Virgen resulting in the concession of considerable territory by the latter hacienda. The 1956 reivindicacion in the province of Cuzco in which Hugo Blanco played a major role was written up by Eric Hobsbawm as a case of neo-feudalism. The labour relations and strategy of resistance was quite different from the 1948 confrontation in the central highlands that I had described (for the framework of resistance strategies see also Hobsbawm, 1969). Yet, it planted the seeds of widespread land occupations in Cusco in 1962. Even within regions themselves tactics differed. On the west side of the Mantaro Valley in the central Andes, the massive campaign of endurance carried out by the Huasicanchinos from 1968 to 1972 resulted in the complete occupation and destruction of Hacienda Tucle and Rio de la Virgen. (Smith 1989; 2014) Yet it differed from the insurgence around Comas to the east of the valley in the late sixties, which itself was different from that of the Tupac Amaru guerrilla close by. (Hobsbawm, 1974; Flores Galindo & Manrique, 1984) A difficulty then, in making a broad assessment of what is going on in ‘Peru’ as a whole is the persistent differences that its many Andean regions face, surfacing time and again in moments of crisis.

From guano to copper to lithium

Currently over forty mining contracts in southern Peru, almost all of them copper, have been paralyzed by popular occupations and blockages, reducing Peru’s copper output by 30% at a time, Bloomberg reports, when copper prices are at their highest. The effect is to halt any attempt at renegotiating Fujimori’s contracts this year. “About $160 million of production has been lost in 23 days of protests” it reported on 27th January. The article concludes “The unrest also jeopardizes the rollout of $53.7 billion in possible investments at a time when the world needs to accelerate decarbonization and boost minerals required for electromobility, according to BTG Pactual analyst Cesar Perez-Novoa.” (Attwood, 2023) The analyst is speaking here of course not of Peru’s longstanding role as a copper exporter but the future contracts for the extraction of lithium.

Agreements for regional resource extraction projects to fund local development such as schools, medical facilities and of course infrastructure (the latter as vital to the miners as to the communities) are pathetic from the outset and unfulfilled to the point of fiction as they unfold. The process is facilitated by mining companies like the giant four, Southern Peru, Yanacocha, Antamina, and Chinalco, signing contracts with Peru’s national police. (EarthRights International, 2019) Use of the police obviously enables the terrorization of locals but has the additional advantage that it allows for the criminal prosecution of protests stoppages and so forth rather than the more cumbersome civil cases that would otherwise be needed.

Meanwhile if brute force isn’t enough, a common practice in sidestepping social contracts of this kind is to offload one mining company to another (often a subsidiary), the conditions of the sale being the abandoning of the obligations of incomplete components an existing social contract. Meanwhile tying up issues of ownership, profit-sharing and social responsibility in lengthy legal proceedings is so common that formulaic contractual obligations to communities can be written into contracts with the full knowledge that they will be held up indefinitely in legal wrangling.

Typical is the following: in 2021 the Macusani Yellowknife lithium extraction project, the largest in Peru, owned by Plateau Energy Metals, itself recently acquired by the Canadian American Lithium Corporation, was disputing 32 out of the 151 concessions it has in southern Peru midway between Cusco and Juliaca. Even so its CEO was able to reassure Resource World Magazine, “While it is standard practise for the legal departments of regulatory bodies in Peru to appeal rulings such as this, the company is confident that, given the strength of judgements in the past the appeals will not be successful,” assuring investors that “common sense will prevail,” and that anyway, while locked up in the courts, the company would push ahead with the mobilization of drill rigs to commence the next phase of development. (Resource World, 2022)

Meanwhile in the much older copper and zinc mines and refining centres to the north – La Oroya and Cerro de Pasco – where foreign contracts are so longstanding that social responsibility conditionalities have to be fought as rear-guard actions, the issues frequently have less to do with recently unfulfilled obligations than generations-long threats both to rural livelihoods and to the possibilities for ongoing social reproduction, in short life itself. On the one hand the pastures in the highlands proximate to those fought over by the montoneros of the past have been so poisoned or simply disappeared as a result of the smelters at La Oroya that endless legal battles for compensation are simply a way of life. On the other hand, in Cerro de Pasco, one of Peru’s main mining cities, children have high blood lead levels, anemia, learning problems, headaches, and nose bleeding leading to endless requests for medical help given that demands for better living conditions over generations have produced only minor results. (Cabral, E & M. Garro, 2020)

The contracts are ubiquitous from one part of Peru to another, be it the southern Andes, the new and old extractive industries of the centre and north, or the oil deposits of Amazonia. But the past histories and present experiences of resistance have their own characteristics.

As the Mexican journalist Luis Hernández Navarro remarks (2023), Peru “is a disabled State that cannot do anything, because everything has to be contracted with private companies.” He refers to Peru’s Quechua name Tawantinsuyo ‘The Four Adjoining Regions,’ And such is the case, four or myriad, Peru remains an incoherent state each of whose regions has had its distinct struggle that from time to time resulted in an all but ephemeral constitutive moment but failed to combine into a synchronous national movement.

Gavin Smith is Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of Toronto and has worked in South America and Western Europe. Apart from ethnographic monographs he has published two books of essays, Confronting the present, 1999; and Intellectuals and (counter-)politics, 2014.

References Cited

Attwood, James. 2023 “Peru’s violent protests imperil 30% of its copper output.” Bloomberg Anywhere 27 Jan. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-01-27/protest-surge-imperils-30-of-copper-supply-in-no-2-miner-peru?leadSource=uverify%20wall Accessed 23 Feb 2023

Cabral, E & M. Garro, 2020: “The bleeding children of cerro de pasco are expecting justice.” Aliados/as: OjoPublico https://ojo-publico.com/2281/bleeding-children-cerro-de-pasco

EarthRights International, 2019: Convenios entre la Policía Nacional y las empresas extractivas en el Perú. Instituto de Defensa Legal, Lima

Flores Galindo, A. and N. Manrique, 1986: Violencia y campesinado. Instituto de Apoyo Agrario. Lima.

Hobsbawm, E.J. 1969, “A case of neo-feudalism: La Convencion, Peru” Journal of Latin American Studies 1,1: 23- 47

Hobsbawm, E.J. 1974: “Peasant land occupations” Past and Present. 62. 120-52.

Manrique 1981: Las guerrilleras indigenas en la Guerra con Chile. Centro de investigacion y capacitacion. Lima

Marini 1981, Dialectica de la dependencia Ed. Era Mexico D.F.

Marini, 2011 “La accumulacion capitalista mundial y el subimperialismo.” Revista Ola Financiera. UNAM. 4,10: 183-217

Mejia, Pepe 2023: “Un huaracazo a la oligarquia” Viento Sur 28 Jan. https://vientosur.info/un-huaracazo-a-la-oligarquia/ Accessed 23 Feb 2023.

Navarro, Luis Hernández 2023: “Movimiento popular destituyente” Viento Sur; https://vientosur.info/movimiento-popular-destituyente/

Poole, D & G. Renique, 2003: “Terror and the privatized state: a parable.” Radical History Review 83:150-63

Resource World Magazine, 2022; https://resourceworld.com/american-lithium-on-dispute-over-peruvian-concessions/ Accessed 23 Feb 2023

Smith, Gavin. 1989: Livelihood and resistance: peasants and the politics of land in Peru. Berkeley, University of California Press.

Smith, Gavin. 2014 Intellectuals and (Counter-) Politics: essays in historical realism. Berghahn. Oxford.

Thorp, R. and G. Bertram, 1978: Peru 1890-1977: growth and policy in an open economy. Columbia University Press, New York.

Zavaleta Mercado, Rene. 2018: Towards a history of the National-Popular in Bolivia 1879-1980. Trans. Anne Freeland. Seagull Books. Calcutta

[1] Pitucos/as is a familiarity used to describe the posh, lazy and shallow elite of Lima. Guano is the Quechua word for sea dung high in nitrates used for fertilizer. The so-called Guano Era during which nitrates were extracted in vast quantities by foreign companies ran from 1802 to 1884 and was a key factor in the War of the Pacific from 1879 to 1884, sometimes referred to as the Saltpetre War.

[2] This was in response to Caceres’s invitation to descend to Huancayo for a war conference. On arrival he and his lieutenants were put up against a wall and shot.

[3] The extent of the montoneros’ successful mobilization against the haciendas over the period is reflected in the number of livestock held before and after the campaign by the two largest of them. Laive: 38,000 sheep before, none after; Tucle 42,000 sheep before, 3000 after. (Smith: 1989: 74) Needless to say in the period that followed the haciendas of the central highlands, most of them owned by those who had collaborated with Chile, expanded without interruption until the 1960s

[4] There is no proper translation for reivindicaciones a term used frequently in the context of rural labourers’ occupation of lands stolen from them.

Cite as: Smith, Gavin 2023. “Peru: the Uncertain State” Focaalblog 3 March. https://www.focaalblog.com/2023/03/03/gavin-smith-peru-the-uncertain-state/