How does Recep Tayyip Erdoğan do it? In Spring 2023, the economy is in a mess, inflation accelerating, and corruption rife. Government aid in the wake of a devastating earthquake in Southeastern Anatolia on 6th February was badly mismanaged. The natural disaster revealed the structural shortcomings of poorly regulated construction and real-estate markets, symptomatic of a political economy given over to short-term profit maximization. In the elections just a few months later, the opposition came together behind an attractive and eloquent candidate, the economist Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. Yet in the second round of voting on 28th May the incumbent triumphed by over two million votes.

If the polls ahead of the election were close enough to rattle Erdoğan, he betrayed no outward sign of discomfort. His imperturbable authority is one of his principal strengths. Critics highlight his control over swathes of the media and the mechanisms through which his Justice and Development Party (AKP) is able influence the votes of state employees. They point to illiberal policies on gender issues (particularly toward the LGTBQ community), arbitrary incarcerations such as that of philanthropist Osman Kavala, and more generally, the repression of a civil society. In his successful mobilization of Islamic sentiment against a secular “deep state” since the closing years of the last century, Erdoğan is categorized by many as a crude populist. In the centenary year of the republic established by Mustafa Kemal (later known as Atatürk), some critics allege that in his two decades of power Erdoğan has fatally undermined the fundamental principles of the secular state. With his AKP party dominating the newly elected National Assembly, the prospect of a more liberal form of democracy emerging in the next five years is tantamount to zero.

Yet within a week of victory, before formally embarking on his new five-year term, Erdoğan made a well-publicized visit to the Atatürk Mausoleum in Ankara. He lauded the transformations of the inter-war decades, following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The extraordinarily high turnout at the May elections, he declared, had once again demonstrated the vitality of the country’s democracy. This ritual occasion was reported in the official media as a ziyaret, a word that has religious connotations in Islam. Has Turkish nationalism been grafted onto Islam such that the mausoleum of Atatürk is now analogous to a religious shrine?

Islamic Capitalism

Erdoğan made his name as a Mayor of Istanbul, but nowadays he regularly loses the biggest cities. He owes his re-election primarily to constituencies in inner Anatolia – including even voters directly affected by the February quake. By unleashing market forces, Erdoğan has continued policies that date back to the very beginning of electoral politics in the wake of the Second World War. Market capitalism struggled to displace a “Jacobin” (Duzgun 2022) variant of modernity which emerged in the late Ottoman era and in secular form continued to dominate in the Kemalist republic. In the changing international climate of the 1980s, Turgut Özal abandoned protectionism and embarked on neoliberal privatizations of state industries. Özal’s Motherland Party demonstrated that capitalism could thrive in an Islamic ideological frame. There were further hiccups and another military intervention in 1997, the Motherland Party faded along with earlier “religious” parties, but in the new century the AKP has sealed the victory of Islamic capitalism: albeit in a political framework that has become ever more authoritarian in the last decade.

What does this mean in practice? It means first of all that the middle classes enjoy greater opportunities outside the public sector and that an entrepreneurial spirit is encouraged in town and countryside alike (For discussion and an anthropological analysis of how small businesses operate in a provincial city, see Deniz 2021). But incentives to invest and consume privately have been accompanied by huge public investments, both in material infrastructure (above all roads) and in social security. Public health provision has improved immeasurably and this contributes significantly to the electoral appeal of the AKP. These welfare accomplishments are seldom acknowledged by the regime’s liberal critics. But critics are right to insist that, far from stepping aside to allow private property and market forces to determine outcomes within an impartial legal framework, the AKP intervenes at every level to enable the proliferation of cronyism and rent-taking (Karadag 2013). Following the bloody attempt by sections of the armed forces and others to depose Erdoğan in 2016 and the transition thereafter from a parliamentary to a presidential system, the patron-client networks of the AKP have become a stranglehold across most of the country – even where a semblance of negotiating “agency” to citizens is allowed (see Evren 2022 for an analysis of how AKP-dominated networks shape the transformation of nature as well as property and power relations locally in a valley of northeast Anatolia).

Nationalism and Ethnicity

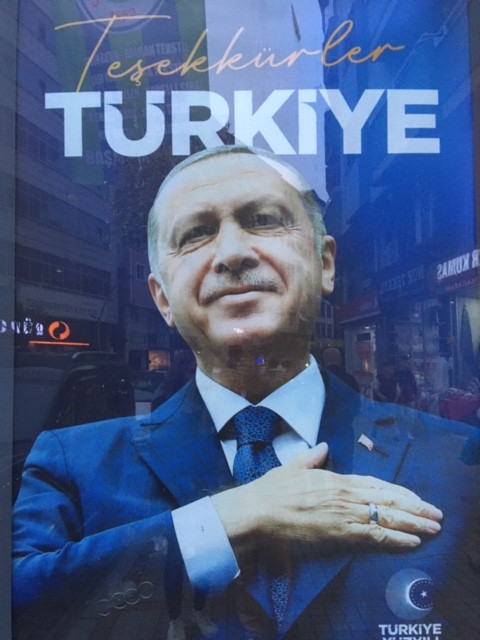

Both presidential candidates played the national card. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu proved savvy in his use of social media, whipping up anti-immigrant sentiment on Youtube in a vain effort to make good his deficit after the first round of elections on May 14th. He had little choice. The party he has led since 2010 is the Republican People’s Party (CHP), which dates back to the era of Atatürk. Traditionally a statist party (“Jacobin” in the political Marxist analysis of Duzgun 2022), the CHP has a much smaller membership than the AKP and cannot generate the donations that might enable it to compete more effectively. In the present conjuncture of Islamic crony capitalism, why would any Turkish businessman be inclined to support the opposition? In the run-up to the elections, the public sphere was awash with posters of President Erdoğan.

Fuller explanations of the outcome of the elections require closer engagement with the decline in ethnic diversity since the emergence of the republic. The Ottomans ruled over an extraordinarily multicultural empire, but nationalist modernization has forged Türkiye (as the country now likes to be known in English) gradually into a more homogenous society. However, some forms of diversity have proved resilient. A common religion and similar experiences of socio-economic transformation have not been enough to endear Kurds to the Kemalist Turkish nation-state. Türkiye’s largest ethnic minority comprises roughly fifteen million members. Although significant internal differentiation persists, generations of conflict have consolidated national consciousness. Kurds outnumber ethnic Turks across most of southeast Anatolia. Many have migrated to the big cities of the west and to Europe in order to improve their economic situation (but not all mobility has been voluntary). Even if they lose their language in the second or third generation, most diaspora Kurds will vote for their own political party whenever they have an opportunity to do so, and seldom for the AKP.

The East Black Sea Coast

These variables play out differently in other regions with smaller minorities and quite different economic conditions. In accordance with the Lausanne agreements, the Pontic Greeks of the Black Sea coast were deported in 1923 (an instance of ethnic cleansing avant la lettre). Their material traces have receded steadily ever since. The splendid Hagia Sophia in Trebizond (today’s Trabzon) functioned for centuries as a mosque before being carefully restored by the Kemalists and opened as a museum in 1964. It was converted back into a mosque in 2013.

The family of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan comes from Rize, which is the last major city on Türkiye’s Black Sea coast, roughly half way between Trebizond and the Georgian border. Its population has doubled to over 100,000 in recent decades and it now boasts a university named after President Erdoğan. In this province, he won over 75% of the vote on 28th May. Most of the east Black Sea coast region is historically conservative and pious. Its subsistence-oriented rural economy was radically altered by changed by the expansion of tea as a cash crop from the 1950s (see Bellér-Hann and Hann 2000). The tea industry was an example of top-down Kemalist modernization, but peasant beneficiaries showed little gratitude and did not change their world view. The CHP has never done well here; in some towns and villages, the principal opposition to AKP comes not from CHP but from extreme nationalists.

But the province of Rize is not homogenous. An hour to the east in the direction of the border crossing to Georgia at Sarp, languages related to Georgian and Armenian are still spoken in the villages. The number of speakers is small and declining (probably below 100,000). In the absence of state support, the prospects for the survival of Lazi and Hemşinli cultural distinctiveness are poor. Unlike the case of the Kurds, ethnicity here does not appear to have an impact on party affiliation and voting behaviour.

However, some minority citizens distance themselves from the Turks of Rize through their pride in being progressive in the Kemalist republican sense. They attach high value to a secular education and social mobility, which almost always implies geographical mobility. A few committed individuals hang posters of Atatürk on their balconies to proclaim their abiding loyalty to the revolutionary secular traditions of the Kemalists. In this way, the man who dominated the public sphere in the last century maintains a presence; but in this election period, it is a modest one in comparison with the Erdoğan images.

This progressive element is strong in the town of Fındıklı, with a population of barely 10,000, which is still run by the CHP. Erdoğan posters are less conspicuous here. In the first round, Fındıklı was the only district of Rize province in which the incumbent President failed to receive 50% of the votes cast. Recently, a new recreational zone including a Lazi cultural centre was created between the sea and the motorway that has transformed the ecology of the littoral (see Genç and Şendeniz 2022). In other towns of Rize and Trebizond, such an initiative would likely have been named after Erdoğan. That was out of the question here. There was pressure from above to bestow the name National Park, but it was finally named Atatürk Park.

But though it is possible to fight the occasional rearguard action successfully, enlightened Lazi landowners nostalgic for Kemalism are not sufficiently numerous to generate an electoral majority against Erdoğan. The success of the tea industry has promoted mobility: the children of the well-educated migrate to the big cities and cast their votes there. Arduous harvesting labour in their native villages is largely undertaken by immigrants, most of whom come from poorer western regions of the Black Sea coast. Some have settled permanently, giving rise to a significant population replacement and hastening the demise of the Lazi language (even activists concede that it would make little sense to teach Lazuri to primary school children who are not of Lazi ethnicity). These sharecroppers retain their conservative worldview. Kemalism has not been as kind to them as it has been to their landlords and the appeal of Erdoğan is strong – sometimes strong enough for them to display posters on quiet country roads. Both owners and sharecroppers approve of the fact that the AKP has refrained from a full-scale privatization of the state enterprise that has set the standard and dominated this sector since the 1950s.

In the second round, after picking up the votes of a candidate further to the right, even in Fındıklı Erdoğan obtained a majority.

Conclusions

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is a gifted politician whose calm autocratic persona goes down well with large sections of the population. He has consolidated his stature as a statesman who stands up for an independent Türkiye on the world stage, whereas his rival Kılıçdaroğlu did little to dispel the view that he would be a puppet of the West, in particular of the USA. Rather like the situation in Hungary in 2022, a fragmented opposition driven to uniting behind a single candidate succeeded only in enhancing the standing and aura of the incumbent.

President Erdoğan is especially popular among citizens with low education and few qualifications. This includes much of the European diaspora as well as post-peasants in Anatolia who continue to the cities but are also prepared to relocate to meet labour needs within the countryside. The evidence from the east Black Sea cost shows that multiple factors interact to shape voting patterns. Uneven development in the Kemalist era has led to new class divisions, while fostering socio-cultural homogenization through new processes of internal migration. The persistence of the state corporation regulating the tea industry symbolizes continuity with statist traditions.

In the centenary year of the republic, Erdoğan is frequently mocked by liberal critics at home and abroad as a throwback to the days of Ottoman Sultans. Comparisons with Mustafa Kemal are perhaps more appropriate. Like his illustrious military forerunner, Erdoğan has transformed his country. The two will blend seamlessly as centenary festivities build up in the second half of this year. Erdoğan’s version of the authoritarian state resonates better with both local religious heritage and global capitalism. He has mastered ways of communicating with the masses that work for this country in this century. Within days of his re-election, the AKP machine was putting up new posters all over the country: in trademark pose, the supreme leader has his right hand on his breast, his lips form a faint smug smile, and the text proclaims “Thanks, Türkiye.”

Chris Hann is Emeritus Director of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology and a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

References

Bellér-Hann, Ildikó and Chris Hann 2000. Turkish Region. State, Market and Social Identities on the East Black Sea Coast. Oxford: James Currey.

Deniz, Ceren 2021. The Formation of Peripheral Capital. Value Regimes and the Politics of Labour in Anatolia. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

Duzgun, Eren 2022. Capitalism, Jacobinism and International Relations: Revisiting Turkish Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evren, Erdem 2022. Bulldozer Capitalism. Accumulation, Ruination, and Dispossession in Northeastern Turkey. New York: Berghahn Books.

Genç Fatma and Özlem Şendeniz (eds) 2022. Beyond the Land. Looking at the Black Sea as a Marine Environment. Fındıklı: Gola Yayınları. Bilingual publication (Turkish title is Karadan Öte: Deniz Olarak Karadeniz’e Bakmak); pdf available at https://golader.org/projeDetay/36

Karadag, Roy 2013. “Where Does Turkey’s New Capitalism Come From? Comment on Eren Duzgun” European Journal of Sociology 54 (1): 147-152.

Cite as: Hann, Chris 2023 “Thanks, Türkiye” Focaalblog 16 June. Thanks, Türkiye https://www.focaalblog.com/2023/06/16/chris-hann-thanks-turkiye/