Published in 2004 in the inspirational context of a veritably exploding anarchism around the world, David Graeber’s Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (referred to here on as Fragments)is a tiny and mighty, genre-defying text. Graeber calls it a pamphlet, “a series of thoughts, sketches of potential theories, and tiny manifestos” (Graeber 2004: 1). The pamphlet is impossible to summarize and discuss fully in twenty minutes, especially since in hindsight, it bears the seeds of many of the major arguments Graeber was to develop later in life. I will therefore limit myself to sketching some basic elements of the kind of social theory that Graeber is proposing in this spirited text. Broadly, Fragments seeks to outline a body of radical theory that would, in Graeber’s words, “actually be of interest to those who are trying to help bring about a world in which people are free to govern their own affairs” (Ibid: 9). This is characteristic of Graeber: the desire to render social theory—particularly anthropology—usefully interesting to radical movements, and radical movements—particularly anarchism—useful and interesting to social theory.

In Fragments, Graeber explores what he names the “strange affinity” between anarchism and anthropology (Ibid: 12). He observes “there was something about anthropological thought in particular—its keen awareness of the very range of human possibilities—that gave it an affinity to anarchism from the very beginning” (Ibid: 13). Graeber himself was fascinated by this, the range of human possibilities in the past and the present, which could unravel the seeming inevitability of our current social and political institutions, while grounding hope for living collectively with greater freedom in more egalitarian arrangements.

Graeber is able to observe the strange affinity between anthropology and anarchism in Fragments because in his version, anarchism is not about a body of theory bequeathed in the 19th century by “founding figures” such as Bakunin, Kropotkin and Proudhon that one would have to adopt wholesale. Instead, it is more about a particular attitude, even a faith that is shared among anarchists (Ibid: 4). Anarchism can be thought of as a faith, Graeber asserts, which involves “the rejection of certain types of social relations, the confidence that certain others would be much better ones on which to build a livable society, [and] the belief that such a society could actually exist” (Ibid: 4). Likewise, the “founding figures” of anarchism did not think they invented anything new—they simply made a faithful assumption that, in Graeber’s words, “the basic principles of anarchism—self-organization, voluntary association, mutual aid—referred to forms of human behavior they assumed to have been around about as long as humanity. The same goes for the rejection of the state and of all forms of structural violence, inequality, or domination.” (Ibid: 3) Arguably, it is this assumption about human history that Graeber sets out to prove valid in his latest book, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, which he co-authored with the archeologist David Wengrow: Humanity has always practiced anarchistic forms of human behavior and social organization—since the Ice Age.

In Graeber’s vision, in any case, anthropology as a discipline could strengthen faith in the possibility of another world by offering an archive of alternative ways of organizing social relations, of reconstituting them consciously, or of abandoning them altogether. But to be able to strengthen this faith in the possibility of another world free from “the state, capitalism, racism and male dominance” (Ibid: 10), social theory itself would have to assume another world is possible. In fact, Graeber asserts this as the first assumption that any radical social theory has to make. “To commit oneself to such a principle is almost an act of faith,” he finds, “since how can one have certain knowledge of such matters? It might possibly turn out that such a world is not possible” (Ibid: 10). In a move that resembles a sophisticated theological argument about the existence of God, he then declares, “it’s this very unavailability of absolute knowledge which makes a commitment to optimism a moral imperative” (Ibid: 10). I wonder, however, if anthropologists or others can be drawn into such faithful optimism by argumentation. Perhaps one could be inspired to have faith in the possibility of another world and inspire David Graeber did along with the radical movements he dearly treasured.

Graeber’s second proposition is that any radical, particularly anarchist, social theory would have to self-consciously reject vanguardism (Ibid: 11). To his mind, ethnography as an anthropological method provides a particularly relevant, if a rough and incipient model of how “nonvanguardist revolutionary intellectual practice may work” (Ibid: 12). The goal of such a practice would not be to “arrive at the correct strategic analyses and then lead the masses to follow” (Ibid: 11), but to tease out the implicit logics—symbolic, moral or pragmatic—that already underlie people’s actions, even if they are themselves not completely aware of them (Ibid: 12). “One obvious role for a radical intellectual is to do precisely that,” Graeber writes in Fragments, “to look at those who are creating viable alternatives, try to figure out what might be the larger implications of what they are (already) doing, and then offer those ideas back, not as prescriptions, but as contributions, possibilities—as gifts” (Ibid: 12). Not prescriptions, but contributions, possibilities, gifts. That is what Graeber offered in his work—particularly in Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, Direct Action: An Ethnography (2008) and The Democracy Project (2013)—whether his gifts were accepted or not by everyone he wrote about, thought and acted with, or, for that matter, was read by. After all, gifts too can be rejected, and as Graeber recognized, not much of what he proposed or practiced as an anthropologist had “much to do with what anthropology, even radical anthropology, has actually been like over the last hundred years or so” (Graeber 2004: 13).

Nevertheless, in Fragments, Graeber turns to anthropologists, most notably Marcel Mauss, to reflect on his influence on anarchists, despite the fact that Mauss had nothing good to say about them. “In the end, though,” Graeber writes as if speaking about himself as well, “Marcel Mauss has probably had more influence on anarchists than all the other [anthropologists] combined. This is because he was interested in alternative moralities, which opened the way to thinking that societies without states and markets were the way they were because they actively wished to live that way. Which in our terms means, because they were anarchists. Insofar as fragments of an anarchist anthropology do, already, exist, they largely derive from him” (Ibid: 21). In my interpretation, Graeber’s own interest in developing an anarchist anthropology too was driven by an appreciation of and fascination with “alternative moralities” that underpin people’s self-conscious determination to live otherwise—in the anarchist case, free from capitalism and patriarchy, free from the state, structural violence, inequality, and domination.

“This is what I mean by alternative ethics” Graeber explains in a critical section of Fragments where he theorizes revolutionary counterpower and foreshadows a core argument he co-authors in The Dawn of Everything (2021): “Anarchistic societies are no more unaware of human capacities for greed or vainglory than modern Americans are unaware of human capacities for envy, gluttony, or sloth; they would just find them equally unappealing as the basis for their civilization. In fact, they see these phenomena as moral dangers so dire they end up organizing much of their social life around containing them” (Graeber 2004: 24). This is a remarkable proposition. First, it is determined to cast ethics and morality as the constitutive, self-conscious grounds of social organization. Second, it intimates this to be the case across human history, “modern” or “pre-modern.”

In fact, Graeber argues that “any really politically engaged anthropology will have to start by seriously confronting the question of what, if anything, really divides what we like to call the ‘modern’ world from the rest of human history” (Ibid: 36). In Fragments, as well as in the Dawn of Everything, he passionately rejects familiar historical periodizations and evolutionary stages such that the entirety of human history—along with every society, people, and civilization across time and space—becomes populated by examples of human possibility enacted by decidedly imaginative, intelligent, playful, experimental, thoughtful, creative, and politically self-conscious creatures.

For Graeber, human history does not consist of a series of revolutions (Ibid: 44)—be it the Neolithic Revolution, the Agricultural Revolution, the French Revolution, or the Industrial Revolution—that introduce clear social, moral, or political breaks in the nature of social reality, or “the human condition” as he prefers to think of it. If this is the case, and if anarchism is above all an ethics of practice (Ibid: 95), as he asserts, such an ethics becomes available for anthropological study and political inspiration across human history. It is important to note however that Graeber passionately disagrees with primitivist anarchists inspired by his anthropologist mentor Marshall Sahlins’ (1972) influential essay “The Original Affluent Society,” anarchists who propose that “there was a time when alienation and inequality did not exist, when everyone was a hunter gathering anarchist, and that therefore real liberation can only come if we abandon ‘civilization’” (Graeber 2004: 55). In Fragments, and the Dawn of Everything, he instead draws a more complex history of endless variety where, for instance, “there were hunter gatherer societies with nobles and slaves,” and “agrarian societies that are fiercely egalitarian” (Ibid: 54). Graeber insists, in other words, that “humans never lived in the garden of Eden” (Ibid: 55). The significance of this finding is manifold. Among other things, it means that history can become “a resource for us in much more interesting ways,” and that “radical theorists no longer have to pore endlessly over the same scant two hundred years of revolutionary history” (Ibid: 54).

Writing of revolution in Fragments, Graeber rejects its commonplace definition which “has always implied something in the nature of a paradigm shift: a clear break, a fundamental rupture in the nature of social reality after which everything works differently, and previous categories no longer apply” (Ibid: 42). Instead, he urges us “to stop thinking about revolution as a thing—‘the’ revolution, the great cataclysmic break—and instead ask ‘what is revolutionary action?’” (Ibid: 45). He stresses that “revolutionary action is any collective action which rejects, and therefore confronts, some form of power or domination and in doing so, reconstitutes social relations—even within the collectivity—in that light” (Ibid: 45), without necessarily aiming to topple a government, or for that matter, the head of an anthropology department.

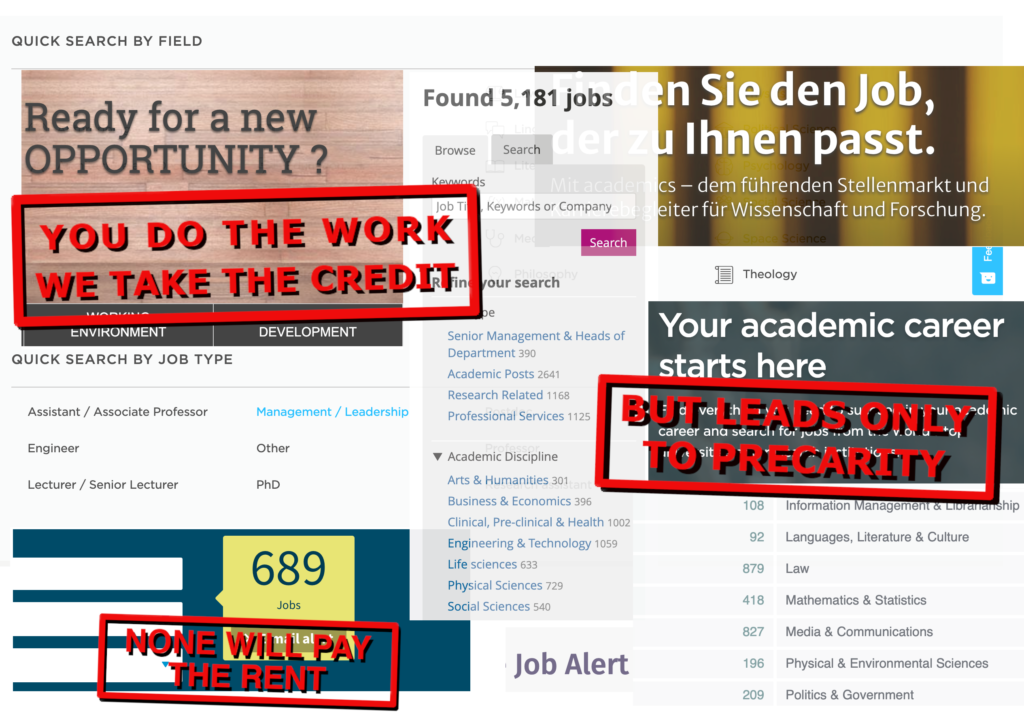

I mention this possibility in the playful spirit of David to bring us back to the here and now, and to the final section of Fragments titled “Anthropology,” in which he “somewhat reluctantly bites the hand that feeds him” (Ibid: 95). Graeber observes how, instead of adopting any kind of radical politics, anthropologists have risked becoming “yet another clog in a global ‘identity machine,’ a planet-wide apparatus of institutions and assumptions,” whereby all debates about the nature of political or economic possibilities are seen to be over, and “the only way one can now make a political claim is by asserting some group identity, with all the assumptions about what identity is” (Ibid: 101), he laments. And bitingly, he declares, “the perspective of the anthropologist and the global marketing executive have become almost indistinguishable” (Ibid: 100).

But what does Graeber propose for anthropology instead? Observing that “anthropologists are, effectively, sitting on a vast archive of human experience, of social and political experiments no one else really knows about,” he regrets that this archive of human experience is treated by anthropologists as “our dirty little secret” (Ibid: 94). Of course, it was colonial violence that made such an archive possible in the first place as Graeber recognizes without reluctance: “the discipline we know today was made possible by horrific schemes of conquest, colonization, and mass murder—much like most modern academic disciplines,” he writes (Ibid: 96). Nevertheless, he makes the daring proposition that “the fruits of ethnography—and the techniques of ethnography—could be enormously helpful” for radical movements around the world if anthropologists could “get past their—however understandable—hesitancy, owing to their own often squalid colonial history, and come to see what they are sitting on not as some guilty secret (which is nonetheless their guilty secret, and no one else’s) but as the common property of humankind” (Ibid: 94).

Towards a conclusion, I would like to submit that anarchism, and the anthropological knowledge of anarchist ethics, practices, and imaginaries across human history are part of “the common property of humankind,” which now includes Graeber’s own contributions to anarchist theory and practice along with his astounding imagination of their possible pasts and futures. Allow me to end then with a strikingly imaginative passage from Fragments, which we could receive as an invitation to think and act towards an anarchist future:

“[A]narchist forms of organization would not look anything like a state. … [T]hey would involve an endless variety of communities, associations, networks, projects, on every conceivable scale, overlapping and intersecting in any way we could imagine, and possibly many that we can’t. Some would be quite local, others global. Perhaps all they would have in common is that none would involve anyone showing up with weapons and telling everyone else to shut up and do what they were told. And that, since anarchists are not actually trying to seize power within any national territory, the process of one system replacing the other will not take the form of some sudden revolutionary cataclysm—the storming of a Bastille, the seizing of a Winter Palace—but will necessarily be gradual, the creation of alternative forms of organization on a world scale, new forms of communication, new, less alienated ways of organizing life, which will, eventually, make currently existing forms of power seem stupid and beside the point. That in turn would mean that there are endless examples of viable anarchism: pretty much any form of organization would count as one, so long as it was not imposed by some higher authority.” (Ibid: 40)

In Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, writing of Madagascar, Graeber observes how “it often seems that no one really takes on their full authority until they are dead.” To my mind, we now have to deal with David’s “full authority” in an anarchist spirit. The task at hand cannot be petrification through idolization or canonization, but the extension of an invitation to think, play, and experiment with his contributions to anthropology and anarchism alike.

Ayça Çubukçu is Associate Professor in Human Rights and Co-Director of LSE Human Rights at the London School of Economics. She is the author of For the Love of Humanity: the World Tribunal on Iraq (2018, University of Pennsylvania Press). Her writing has appeared in the Law Angeles Review of Books, Jadaliyya, The Guardian, Al Jazeera English, Thesis 11, Public Seminar and other venues. Ayça is a member of the editorial collectives of the Humanity Journal, Jadaliyya’s Turkey page, and of the LSE International Studies Series at Cambridge University Press.

This text was presented at David Graeber LSE Tribute Seminar on ‘Anarchist Anthropology’.

References

Graeber, D. 2004. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Graeber, D. 2008. Direct Action: An Ethnography. California: AK Press.

Graeber, D. 2013. The Democracy Project: A History, A Crisis, A Movement. New York City: Spiegel & Grau, a publishing imprint of Penguin Random House.

Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. 2021. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. London, UK: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books.

Sahlins, M. 1968. “Notes on the Original Affluent Society.” In Man the Hunter: The First Intensive Survey of a Single, Crucial Stage of Human Development—Man’s Once Universal Hunting Way of Life, Lee and DeVore (eds), pp. 85-9. Chicago: Aldine.

Cite as: Ayça Çubukçu. 2022. “On Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology.” FocaalBlog, 18 January. https://www.focaalblog.com/2022/01/18/ayca-cubukcu-on-fragments-of-an-anarchist-anthropology/