Africa’s Green Energy Revolution

This post is part of a feature on “The Political Power of Energy Futures,” moderated and edited by Katja Müller (MLU Halle-Wittenberg), Charlotte Bruckermann (University of Bergen), and Kirsten W. Endres (MPI Halle).

In the past ten years, calls for a “green revolution” on the African continent have cast optimistic and promising scenarios of “leapfrogging” to mass renewable energy generation in order to meet the continent’s targets for electrification and forecast growth for energy demand. With a population expected to increase by 800 million by 2040 with rising urbanisation, the most pressing challenge for the continent in the next 20 years will be to meet growing energy demand in a context of partially-present and unreliable infrastructure (IEA 2019). Renewables have been positioned as a technological messiah of development, enabling the continent to “leapfrog” traditional models of centralized grid-based electricity distribution and to radically green its economies (IRENA 2015). The IRENA 2030 roadmap for Africa’s renewable energy, for instance, suggests that renewables could in the next 20 years constitute half of Africa’s total energy mix (IRENA 2015) – pending an estimated USD $70 billion investment a year. Yet current solar PV installed capacity on the continent only accounts for 5GW, or one percent of the global total (around 600GW) (IEA 2019). Visions of a renewable “energy renaissance” (Olopade 2015, 15) in Africa remain blighted by the current reliance and increasing dependence of African countries on imported oil and fossil-based energy use, and of the continued (and new) opportunities for oil and gas extraction. In turn, discourses of energy transition and leapfrogging, with their unilinear trajectories and singular vision of a low-carbon future, tend to obscure the local specificities and histories of energy systems like Ghana’s, for whom renewable energy, in the form of hydropower, has long been its main source of energy generation.

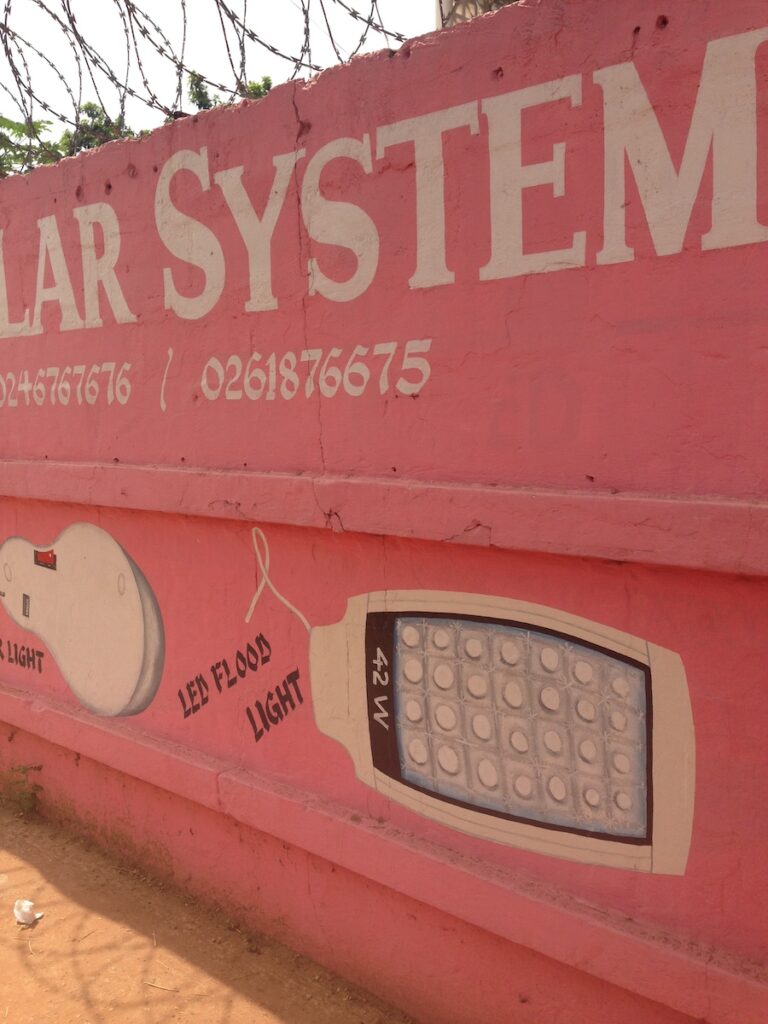

In this post, I look at the contested politics of renewable energy in Ghana through a focus on the rise of “corporate solar” during an energy crisis. Ten years ago, shortly after the country discovered oil in large quantities along the coast of the Western Region, it embarked on an ambitious renewable energy path by passing the Renewable Energy Act (2011) (Act 832). The Act aimed to promote and develop the country’s renewable energy resources to ensure the country’s energy security, indigenous capacity and sustainable development. Ghana’s initial target was to increase the renewable electricity generation share, currently at less than one percent, to ten percent by 2020 (Sakah et al. 2017). Ghana thus positioned itself as West Africa’s new “energy frontier”, ushering in a resurgence of fossil extractivism paired with ambitious support for renewable energy technologies (Degani, Chalfin, and Cross 2020). In the midst of oil and gas discoveries, renewables have become a strategic, moving target conveniently reformulated to fit political agenda and rhetoric (Obeng-Darko 2019). For reasons of space, I will not elaborate on the ways in which new oil production came to stymie the growth of renewables. Instead, I provide a snapshot of solar power’s new corporate contours of energy privilege in Accra. I identify the emergence of a “renewable divide” in urban Ghana through the rise of “green enclaves” mostly enjoyed by corporate bodies and wealthy individuals. Building on the recent literature in the anthropology of energy challenging the “fantasy” of solar as a promise of democratic energy access (Szeman and Barney 2021), I consider how energy disparities endure under the transition to cleaner and renewable energy sources.

Moratorium on the Future: Renewables as Stranded Assets

In 2019, at an event on renewable energy opportunities for the private sector, a representative from the Renewable and Alternative Energy department at the Ministry of Energy made an unpopular announcement. Referring to the 2011 Renewable Energy Act, he declared that Ghana was not only on track to meet its target for 10% of total energy generated by renewables, but that it had met its target “long ago”, since the Akosombo Dam, which was built in 1966 by Kwame Nkrumah and accounts for 27% of the country’s total capacity, was technically a source of renewable energy.

Invoking the country’s proud history of electrification through the Akosombo Dam – a key project in Nkrumah’s vision for African industrialization and self-sufficiency (Miescher 2014) – and its negligible contribution to global carbon emissions, he declared the matter closed. Rather than seeking to please international conventions that did not adequately capture Ghana’s place in the global responsibility framework for climate change mitigation measures, he concluded that Ghana, like other African countries, would do well to focus instead on providing enough power for its people and industries.

Renewable energy companies’ representatives, entrepreneurs and analysts were shocked by the Minister’s backtracking commitment. That same year, as a result of overcapacity on the national grid, the government had issued a moratorium on PPAs (power purchase agreements), banning any addition to its grid until 2027. Since then, utility-scale renewable energy projects have come to a stall, leaving many with “stranded assets” and uncertainty about the future viability of large-scale solar PV and wind farms in the country. Of course, the Minister wasn’t technically wrong to claim the Akosombo Dam as a source of substantial renewable energy in the country’s electricity generation mix. To the renewable energy industry, however, it was perceived as a betrayal of the prevailing understanding that the target referred to additional capacity-building, mostly in the form of solar PVs and wind turbines.

Corporate Solar & The Renewable Divide

The moratorium on renewable energy PPAs exacerbated the inequalities that solar power has created in Ghana’s energyscape. Today, the largest clients for solar companies in Ghana are banks, hotels and factories – corporate bodies that have the capital for upfront costs. Following the frequent blackouts during the energy crisis that best the country in 2014-2016 (locally known as “Dumsor”), and the steep increase in electricity tariffs, many businesses, particularly factories in the industrial zones, switched to distributed generation, adopting solar as a “commercial strategy” to reduce their costs of manufacturing. “Dumsor” is Twi for “off-on”, a shorthand for the power outages that have become increasingly common in the country; today, the word has come to index a more general situation of disenchantment with infrastructure delivery and political expediency. Solar energy companies were quick to capitalise on the crisis as a business opportunity. In 2016, when I was researching Dumsor for my PhD thesis, I spoke to the representative of an Indian solar company with a large global presence who told me that initial investments in solar energy in Ghana prior to the crisis had been minimal because the power sector was “too good” and “too stable” for profit, compared to countries like Nigeria or Egypt that had more frequent power cuts and thus a bigger potential market.

In the turn to solar as a panacea for crisis, large corporate bodies removed their operations from the national grid, alternating between distributed solar and diesel-powered generator sets. This commercialization of distributed solar has further strained the financial situation of the national utilities, heavily dependent on industrial consumers’ revenues to subsidize residential low consumers. This has resulted in higher electricity tariffs for urban residential consumers, making electricity increasingly unaffordable to many. The capacity to switch to solar during a moment of crisis revealed new forms of energy privilege that take place outside the grid. In turn, the adoption of solar by a select elite (cf. Günel 2021) has further exacerbated the conditions of energy inequalities and precarity that many Accra residents live under. In the low-income neighbourhood of Western Accra where I have been doing fieldwork since 2014, this “renewable divide”, as we may call it, crossed two types of association. My neighbours and interlocutors perceived rooftop solar as a luxury item unaffordable to most, or as a humanitarian good reinforcing unequal trajectories of transition between the global North and the global South.

Here, “corporate solar” coexists with the “developmental” deployment of small-scale solar (in the form of solar lanterns and mini-grids) introduced by NGOs and small social enterprises in rural areas. The parallel trajectories of corporate and non-profit interests may appear surprising, operating as they do in divergent moral economies. Both types of solar projects, however, are driven by the same material, political and economic advantages of solar, as a form of cheap, reliable and distributed generation that offers autonomy from the inefficiencies of state infrastructure (Cross 2019, 54).

In effect, both “developmental” and “corporate” solar contribute to what may be called the creation of “green enclaves” in the energy landscape of Ghana, pockets of autonomous, renewable energy that serve both corporate and humanitarian rationales. I borrow the term “green enclave” from an engineer of the Volta River Authority (VRA) responsible for the hydropower generation plant at the Akosombo Dam that provides a large part of Ghana’s generation capacity. At a convention for renewable energy in Accra in 2019, he described to me plans to install solar panels on the roofs of Parliament, ministries, and the residential facilities at the Akosombo dam as “the greening of our enclaves”, a term that fittingly describes the infrastructural model of renewable energy at large in the country. It is not surprising that the Minister who had conveniently re-adjusted Ghana’s renewable energy target himself had solar panels installed on his house.

In a context of widespread energy precarity, solar in urban Ghana has exacerbated inequalities of access to reliable and affordable electricity, creating “green” geographies of inequality, energy security, and privilege.

Conclusion: Energy Transitions in perspective

Ghana’s case-study has important implications for understanding energy transitions around the world. In popular discourses of energy transitions, the replacement of fossil fuel dependencies by renewable energy sources seems both inevitable and imperative. Calls for a renewable energy revolution in Africa are appealing, but they too often assume that renewables come to fill a gap, a lack, or an evidential need – in other words, that their benefits are too self-evident to forgo. Renewables, in this case, belong to the future – and fossil fuels to the past. In many ways, Ghana presents an inverse scenario of this dominant model of transition. Having powered most of its electricity needs with hydropower, it is now switching to increased reliance on thermal power plants and an oil economy. Further, this past of renewable energy through hydropower is today invoked to encourage a rush for oil and gas exploitation. In discussions with energy officials, policymakers, and the general public, I am repeatedly reminded that “Ghana is a low emitter”, bearing no responsibility to global greenhouse gas emissions. For a country that relied until recently entirely on hydropower for electricity, yet currently faces issues of reliability and affordability (Eshun and Amoako-Tuffour 2016), “sustainability” appears as a secondary concern to more pressing issues of overcapacity and improving access to reliable and affordable power. In turn, the adoption of renewables may not primarily be motivated by questions of environmental ideology, but also as a convenient (if privileged) solution to crisis. Accounting for the political potential of renewable energy futures around the world will demand that we grapple with the contradictory, divergent and conflicted visions and temporalities of energy transitions, and the relations between crisis and capital, privilege and poverty through which they come into being.

Pauline Destrée is a Research Fellow in the Department of Anthropology at the University of St Andrews. She is a member of the ERC-funded research project Energy Ethics. Her research explores energy, extraction, climate change, gender and race in Ghana.

Twitter: @PaulineDestree https://twitter.com/PaulineDestree

Bibliography

Cross, Jamie. 2019. “The Solar Good: Energy Ethics in Poor Markets.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 25 (S1): 47–66.

Degani, Michael, Brenda Chalfin, and Jamie Cross. 2020. “Introduction: Fuelling Capture: Africa’s Energy Frontiers.” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 38 (2): 1–18.

Eshun, Maame Esi, and Joe Amoako-Tuffour. 2016. “A Review of the Trends in Ghana’s Power Sector.” Energy, Sustainability and Society 6 (1): 9.

Günel, Gökçe. 2021. “Leapfrogging to Solar.” South Atlantic Quarterly 120 (1): 163–75.

IEA. 2019. “Africa Energy Outlook 2019.” Paris: IEA.

IRENA. 2015. “Africa 2030: Roadmap for a Renewable Energy Future.” Abu Dhabi: IRENA.

Miescher, Stephan. 2014. “‘Nkrumah’s Baby’: The Akosombo Dam and the Dream of Development in Ghana, 1952–1966.” Water History 6 (4): 341–66.

Obeng-Darko, Nana Asare. 2019. “Why Ghana Will Not Achieve Its Renewable Energy Target for Electricity. Policy, Legal and Regulatory Implications.” Energy Policy 128 (May): 75–83.

Olopade, Dayo. 2015. The Bright Continent: Breaking Rules and Making Change in Modern Africa. Reprint edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt USA.

Sakah, Marriette, Felix Amankwah Diawuo, Rolf Katzenbach, and Samuel Gyamfi. 2017. “Towards a Sustainable Electrification in Ghana: A Review of Renewable Energy Deployment Policies.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 79 (November): 544–57.

Szeman, Imre, and Darin Barney. 2021. “Introduction: From Solar to Solarity.” South Atlantic Quarterly 120 (1): 1–11.

Cite as: Destrée, Pauline. 2021. “Solar for the Few: Stranded Renewables and Green Enclaves in Ghana.” FocaalBlog, 9 April. https://www.focaalblog.com/2021/04/09/pauline-destree-solar-for-the-few-stranded-renewables-and-green-enclaves-in-ghana/