One of the main strengths of ethnographic methodologies is immersed, long-term research, which enables in-depth learning and a holistic vision of a given issue. Restricted or volatile access to ethnographic field sites thus presents not just practical difficulties but it raises a host of important methodological, epistemological, ethical and other questions.

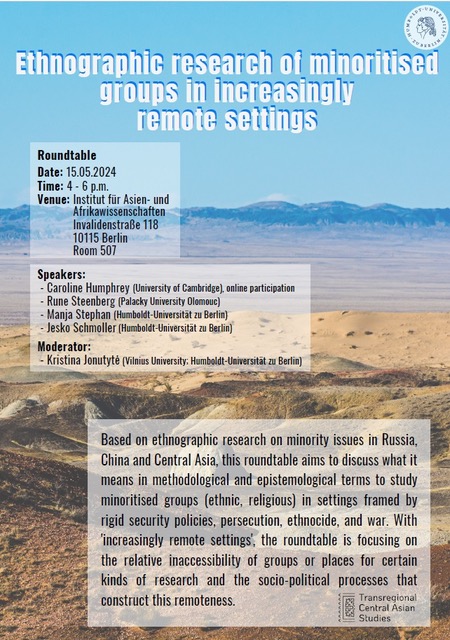

A roundtable discussion at the Institute for Asian and African Studies at Humboldt University of Berlin brought together scholars working in the fields of anthropology and area studies sharing their experiences of conducting ethnographic research in places that appear increasingly inaccessible due to political conflicts, war and rigid authoritarian regimes. In such contexts, the study of minoritized populations (ethnic, religious) is often particularly unwelcome by the dominating regimes, as they may experience rigid security policies, second-class citizenship, and even persecution. At the same time, the predicament of minoritized groups may thus require greater outside visibility and scrutiny.

Roundtable participants discussed the contexts of contemporary Russia, China, and places in Central Asia such as Tajikistan, which had been relatively accessible for various forms of social scientific research but this has changed in recent years because of shifting domestic and international politics. These places, like many others around the world, can be thought of as “increasingly remote”, referring both to their relative inaccessibility to certain kinds of research as well as to the social and political processes that construct such remoteness (Harms et al 2014). Remoteness here is not an absolute category, but a relative and changing one, related to one’s positionality, perspective, power, and other factors, as well as related to processes of marginalization and minoritization. We are particularly interested in what this “return of remoteness” (Saxer and Andersson 2019) means for ethnographic research. How can scholars continue doing research in/on such settings? How are they being affected (professionally, personally) by the changing circumstances? What are the ethical challenges of such studies, especially with regard to the personal safety of research partners? And what political responsibilities does it entail for anthropologists and area studies scholars who do research in politically sensitive settings?

Methodologically, too, “increasingly remote” settings pose significant challenges. First-hand in-depth knowledge appears especially important in such contexts, while also being difficult to obtain. We thus asked: Which approaches or strategies do scholars opt for? Can remote ethnography, material culture studies, new area and mobility studies or other approaches provide substantial alternatives when in-person fieldwork is not possible? Roundtable participants reflected on how changing accessibility of their field sites has shaped their research questions and approaches.

Having started her ethnographic research in Buryatia – then part of the Soviet Union – in the late 1960s, Caroline Humphrey recalled selecting the seemingly least problematic topic of study – kinship – knowing many other issues like politics or religion were strictly off limits. However, she soon found that through kinship, she could indeed access many other important issues that could otherwise hardly be discussed, like tragic family histories due to communist policies. Over time, accessibility shifted in her field: from the initial Moscow-supervised official field visit to more informal visits in the 1970s, 1990s and early 2000s, where she found research participants to be more open about a wide range of topics, through to an officially permitted visit in the borderland region in the 2010s. Throughout these changeable circumstances, Caroline highlighted lasting friendships as key to successful fieldwork under uncertain conditions. More recently, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Buryatia has grown once again grown “remote” for fieldwork but, as Caroline suggested, it might be more accurate to say that it has been distanced from the perspective of the researcher, who chooses not to go there to ensure the safety of interlocutors. She highlighted a range of ethical challenges that have emerged doing research in the region, like choosing not to publish some of the data to protect interlocutors, highlighting a thread of fear and concealment among locals, especially minoritized groups, due to the history of repressions and their often precarious situation today. At the same time, she noted that the researcher’s position also changes over time, and with it access to various field sites, groups and resources shifts, too. Finally, Caroline noted she finds it important to keep in touch with colleagues in “increasingly remote” Russia and exchange with them professionally rather than engage in academic boycott.

Rune Steenberg’s field site in Xinjiang was rather difficult to access from the beginning of his field research in 2009, but still manageable for low-profile visits up to 2016. As China’s policies in the region grew more oppressive, in-person research for him was no longer viable. Since then, he has utilized a variety of approaches from doing Uyghur-related ethnography outside of Xinjiang, remote ethnography, textual and online research to working collaboratively with researchers, diaspora and others who could access the region in one way or another. Arguing that ethnographic research is always already limited as access is restricted by our positionality, cultural norms, and a range of other factors, Rune nonetheless believes that whenever possible, remote research should be supplementary rather than a substitute to in-person research. Currently, he leads a group project “Remote ethnography of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region”, combining a variety of remote methods to study this region inaccessible to most researchers, marked by extreme state violence and human rights violations. Through this multifaceted experience, Rune has found that remote ethnography is best as a group endeavor, multiple perspectives and approaches adding value to the whole.

Manja Stephan’s selected research topic of Muslim mobilities led her far outside of her initially selected place of study in Tajikistan. Due to the fear of Islamization, religious students she sought to do fieldwork with were increasingly marginalized and criminalized in the country, as securitization of Islam grew. As a consequence, she found translocality and mobility studies to be more suitable research approaches, rather than place-based ethnographic study. Mobility biographies she collected as part of her research led her not only to Dubai where she did in-person fieldwork with Tajik migrants, but also to places like the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Russia. Remoteness being a matter of power and a politically constructed condition, Manja’s fieldwork was framed by national policies, as her research participants themselves grew “remote” from mainstream Tajik life. This is one example of a situation of “authoritarianism paradox”: the more difficult it is to research a given minoritized group in an authoritarian setting, the more interest there may be in doing so, and the more necessary it is to undertake such research to draw attention to the position and voices of locals. At the same time, as in-person research in such contexts is severely limited, macro-level studies from afar, which have a tendency towards simplification, gain prominence over ethnographic research.

Conducting research in Bashkortostan, Russia, Jesko Schmoller has found his field site physically inaccessible since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Since his research primarily focuses on place, exploring Muslim place-making in Bashkortostan, restricted access appeared as an especially significant obstacle. While Jesko hopes to return to in-person fieldwork when it is once again possible, for now, he found textual studies to be unexpectedly eye-opening, providing insight into important aspects of Bashkir culture and religion previously unknown to him. He found that ethnographers should ideally be working with primary texts more even if they have good field access. Initially skeptical of relying on text too heavily, he now works with original Bashkir texts, such as Ufa-published “Bashkortostan: the land of Awliya [Friends of God]”, with a focus on religion and space. In his current research, he asks: What insight can be gained into sacred space through primary texts? Can they provide insight into a growing spatial marginalization of Muslims in Russia? Can one be in proximity to sacred places via text and gain insights into local ontologies (rather than discourses) without being there in person? From a local Sufi Muslim perspective, for instance, the Bashkir sacred landscape exists on yet another plane than the physical one. May such texts be regarded a medium to gain a sense impression of this kind of concealed geography?

Like Jesko, other speakers try to approach the newfound remoteness as an opportunity rather than a limitation. Rune and Manja both recounted that when they did research with participants outside of their repressive home country, they were much more open and research was more productive. Another opportunity provided by remoteness was various local publications as noted by Jesko Schmoller and Caroline Humphrey, who noticed an increase in local publications across Russia – as perhaps also in other regions – which provide a treasure trove to anthropologists who can rely on them as data, given their preexisting in-depth knowledge of the context. Another remote method that Caroline has made use of together with David Sneath (1999) in “The End of Nomadism? Society, State and the Environment in Inner Asia” was remote sensing, namely using satellite photography to make visible the effects of contrasting land-use systems along the Russian-Mongolian border. While this method provided important insights into local environmental changes, Caroline stressed the difficulties involved in interpreting remote sensory data and the necessity to triangulate it with other kinds of knowledge. Rune Steenberg, too, regularly uses various kinds of remote sensing data in his research, extracting significant information even from tourists’ videos and travel accounts. He stressed that “epistemological care” is of utmost importance in remote research: transparency about the certainty of arguments made in remote ethnographic research provides an important corrective in precarious research contexts.

Moreover, Caroline argued that remote research widens the scope of ethnographic investigation, as it is no longer confined to the researcher’s physical presence. At the same time, it may become more similar to historians’ research techniques. Relatedly, Manja asked: if ethnographers lose access to in-person fieldwork and rely only on remote data, what is it that specifically ethnographic remote research contributes? To Rune, the answer lies in ethnography’s holistic approach and in the thick description that uncovers multiple layers of meaning and perspectives. This is enabled by deep immersion in a local context through ethnographic methods but if need be, one can even undertake artificial immersion away from the research area, through a period of intense engagement with local media, social media, communicating in the local language with people from there and other means. Also, “classical” ethnographic fieldwork outside of the inaccessible region is often part of remote ethnographic methodologies.

Caroline raised another important question: what can ethnographers doing remote research contribute that would differ from and add value to what the diaspora or other critical voices of the studied group are already saying? While this question requires a broader discussion, as preliminary remarks, Rune suggested that while cooperation with members of the diaspora is crucial, it is also important to note that they often have their own visions and agendas, so social scientific methodologies and analyses are a meaningful contribution. Manja added that working solely with members of the diaspora may provide little representation of the social, economic, cultural and other diversity of society in their homeland.

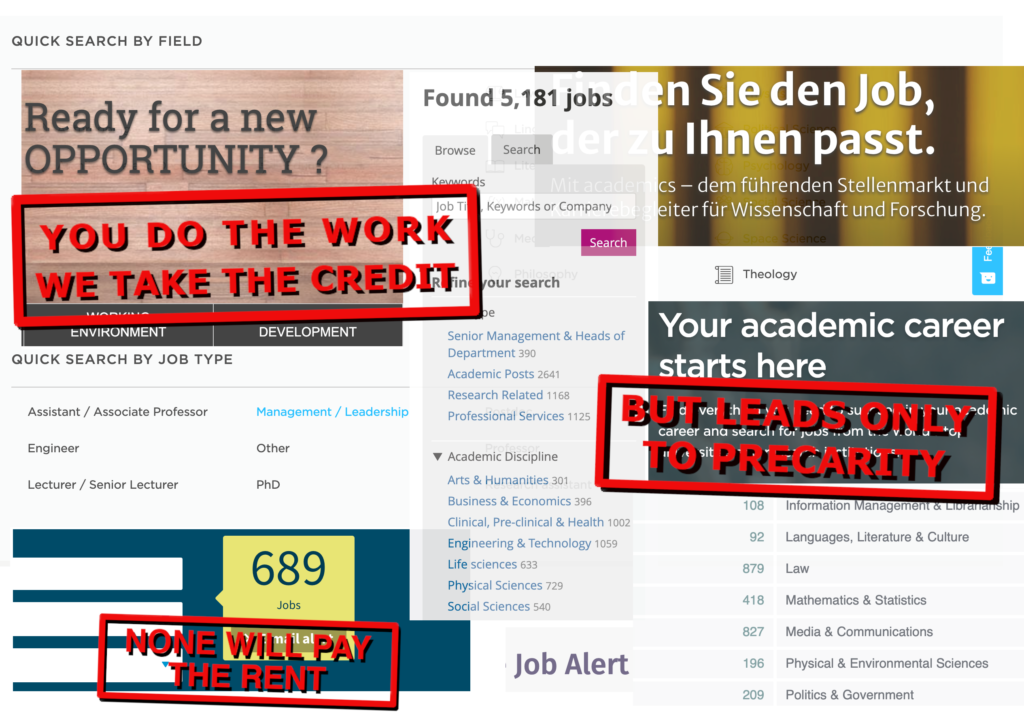

The role of institutions appeared as important to the speakers, all of whom strove towards strong connections on the ground rather than an official veil to their research. Yet this is not always possible, like in Caroline’s initial fieldwork, where Buryat collective farms could only be accessed with official approvals from both Moscow and the Buryat authorities. Manja spoke of a seemingly growing expectation institutions hold towards researchers to engage in “scientific diplomacy” along their research responsibilities, acting as representatives of their institutions and even nation-states in the field. These roles can be difficult to balance and even disadvantageous for some kinds of research, shaping ethnographer’s relationships in the field. Finally, Rune stressed the importance of critically engaging with the institutions we partake in, such as universities. Their growing neoliberalisation is a significant component of the broader, global political processes that reproduce the kinds of conditions for human rights abuses, surveillance, marginalisation and precarity in the places we study. Opposing structures that reproduce inequalities in our home societies is therefore important in beginning to oppose them in places of research.

Bibliography

Harms, Erik, Shafqat Hussain, and Sara Shneiderman. 2014. “Remote and edgy: new takes on old anthropological themes.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4(1): 361–381.

Humphrey, Caroline, and David Sneath. 1999. The end of Nomadism?: Society, state, and the environment in Inner Asia. Duke University Press.

Saxer, Martin, and Ruben Andersson. 2019. “The return of remoteness: insecurity, isolation and connectivity in the new world disorder.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 27(2): 140-155.

Dr. Kristina Jonutytė is an associate professor at the Institute of Asian and Transcultural Studies, Vilnius University. Her research interests lie in political anthropology and the anthropology of religion, with an ethnographic focus on Buryatia, Russia and Mongolia. The present text was prepared during a visiting fellowship at the Central Asian Seminar, Institute of Asian and African Studies, Humboldt University of Berlin.

Cite as: Jonutytė, Kristina 2025. “Ethnographic research of minoritised groups in increasingly remote settings: A roundtable discussion” Focaalblog 20 February. https://www.focaalblog.com/2025/02/20/dr-kristina-jonutyte-ethnographic-research-of-minoritised-groups-in-increasingly-remote-settings-a-roundtable-discussion/