The Eastern edges of the European Union stand as landscapes of transformation and socioeconomic and cultural flux, situated between shifting empires and layered histories. Their in-betweenness mirrors a duality of political imaginaries: remnants of collapsed past utopias colliding with the alluring yet hollow promises of contemporary global capitalism. These places also inhabit the peripheries of the contemporary art market, providing an infrastructure that feeds into neoliberal logics and fosters opportunities for some while relying on the precarity and exploitation of others (Malik, 2019). Yet, it is precisely this peripheral, liminal position that enables the Eastern edges of the European Union to cultivate specific types of localised knowledge, dialogue, and conversations that would resonate differently if held at the centre of the capitalist world system. Thus, in this blog post, we assess the fleeting potentiality of thinking ‘between the Posts’ (Chari & Verdery, 2009)—that is, examining both colonial and socialist histories–in possibly providing a richer, hybrid framework not only for intersectional critique but also for new political imaginations and coalitions to emerge.

We want to illustrate this with reference to the postcolonial and postsocialist encounters we came across at the Kaunas Biennial, Long-Distance Friendships, and the Ljubljana Biennial From the Void Came Gifts of the Cosmos, which took place in 2023. While in the fast-paced world of art critique with its immediate reporting, looking back at past cultural events a year or so later might seem unorthodox, we see value in slower forms of reflection.

Attending the two events, we were curious to see how the two art biennials realised their ambition to invite postsocialist subjects to reflect on coloniality. What are the benefits when postcolonial conversations are situated in geographical settings that have different histories of capitalism and anti-capitalism than world-leading biennials such as Venice? This text is a reflection of our ambivalent and interwoven positionalities spanning research, art, and activism in ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ Europe, and our life and work mobilities between Belgium, Slovenia, and Lithuania.

We grappled with the discourses emerging in the frameworks of the biennials as anthropological artefacts, pondering how they travel, morph, germinate, and fade out. What are their political economy, impact, and historical reference points in a world region outside the capitalist bloc during the Cold War, for example? Who are the artists invited to work with and articulate these reference points, and under which conditions? For this project we took research trips to Kaunas and Ljubljana and conducted interviews with institutional representatives, curators, and artists.

From the void // came gifts

With the notion that ‘from the void came gifts of the cosmos,’ the artistic director, Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama, and a group of curators were invited by the MGLC (Mednarodni grafični likovni center;transl: International Centre of Graphic Arts) for the 35th Graphic Biennial of Ljubljana (founded in 1955), to initiate an exchange among the works of 44 artists and 11 historical artworks from the biennial’s archives. The historical ties post-independence Ghana and former Yugoslavia as member-states of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM, founded in 1961 as a forum of countries not aligned with either of the two major power blocs of the Cold War) were seen as legacies to build on for new solidarities between Slovenia (and Eastern Europe at large) and the Global South.

Ibrahim and the curators took the expansive notion of ‘The Void’ as an uncontrolled space with inherent radical potential for equality as the point of departure for their work. Under circumstances where we need more conceptual tools to grasp emerging alliances at the interstices of global powers and common forms of dispossession—such as those related to the environment—the biennial’s departure from ‘The Void’ proved stimulating. Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh, a curator based in Kumasi, Ghana, explained in an interview how the notion of ‘The Void’ can unveil the promises and failures of post-independence politics and transnational friendships, such as the Non-Aligned Movement.

To transcend hegemonic binary logics and think through “universality from the periphery” means, in Kwasi’s words, “to take the poison, and out of it, generate something progressive”. The curators embraced the void as a means of reconciling with and affirming the role of the arts in constructing new imaginaries and alliances between the Global South and Global East beyond the monopoly of Western power (Ohene-Ayeh et al. 2023). With this, they echoed Ghanaian artist-intellectual kąrî’kạchä seid’ou’s vision of transforming art from commodity to gift as a way to challenge art’s capitalist underpinnings and to foster alternative forms of exchange.

An important aspect of the 2023 exhibition was therefore a reflection on the history of the Graphic Biennial as both a generator and a product of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia’s cultural diplomacy. While the Ljubljana biennial convincingly linked post-independence, postcolonial, and socialist artworks and global alliances of the Cold War period to the question how political projects can fill ‘The Void’, it also left a void in addressing how artists can liberate themselves from the neoliberal regimes of contemporary art to connect with the material conditions of local struggles against rapid neoliberalisation. An immediate display of this project came from the local grassroots art scene in Ljubljana as the local Krater Collective contributed an artwork that showcased the negotiations over the material terms and conditions of the Graphic Biennial.

“A place we call home”

The Ljubljana biennale showed many international artists, particularly from the Global South, but it is the participation of Tjaša Rener which unearths the unorthodox and less mediated mobilities from South-Eastern Europe to the Global South. Rener is a Slovenian-born artist who has been living in Ghana for over a decade. For the exhibition venue at Cukrarna she had prepared an installation called A Place we Call Home, which juxtaposed her own positionality with that of another Slovenian-born woman named Metoda. While both the artist as well as her subject are presented as outliers to the more common routes of the global mobility regime, their personal routes were four decades apart. In those four decades, the political system of their place of origin changed. For socialist Yugoslavia, which had no prior tradition of international education, cooperation with socialist countries in Africa brought an influx of international students to its nascent socialist education system (Dugonjic-Rodwin & Mladenovic, 2023). One of them was Metoda’s now deceased husband, who came to Yugoslavia as a student on the NAM’s programme of bilateral collaborations and with whom Metoda moved to Accra in 1974. A place she has made her home.

Metoda’s house in Accra is the central motif of Rener’s work for the Graphical Biennale. The installation combines archival photographs, historical objects, and a painting to evoke both Metoda’s home in Accra, memories of 1980s Slovenia, and the artist’s own childhood home, her mother’s house. In the corner, an old radio is playing excerpts from interview with Metoda, capturing the gradual, but enduring erasure she faced as socialist Yugoslavia collapsed and she was in Ghana as a citizen of a nation that was no more, while Ghana’s digitalization of national registers made it difficult to access her administrative and legal documents and rights. The artist compares Metoda’s experience with that of the so-called ‘Erased” in Slovenia, residents mainly from states of former Yugoslavia and of ethnic minority status with similar experiences.

The artwork compels us to think through complex mobilities and modes of identity construction of postsocialist subjects in a postcolonial space, in which the artist and Metoda interact through a shared language, the debris of historical ties and recent attention to relations between socialist Eastern Europe and postcolonial nations. While it is tempting to read non-alignment –- both in the work of Rener, as well as the larger framework of the biennial – as re-affirming the nation state as a point of reference and belonging, another reading highlights its internationalism and the internationalist outlook it offered to citizens of socialist Yugoslavia and others (Dugonjic-Rodwin & Mladenovic, 2023).

The artist evokes a gendered sensibility to read the historical (diplomatic) ties between former socialist and post-colonial countries, while using her own positionality between Ghana and Slovenia as a lens to explore the multiple articulations of identity and belonging, race and class, and the changing mobility regimes under non-alignment and neoliberal capitalism.

Fabricating resistance between the posts

The Kaunas Biennial centred on personal histories, relationships, and their potential. By bringing together artists from Lithuania, the African continent, and beyond—many of whom created works on the event site—the curators facilitated a space not only for an exhibition but also for collective thought and work. The main exhibition venue, a modernist post office building in Kaunas, served as both a space where artists created works on site and a nod to the historical ties of communication and exchange among countries under former Soviet and colonial rule, as well as present and possible future entanglements.

Often, the contemporary art scene in the Baltic states has adopted a Western postcolonial framework that reproduces the binary coloniser/colonised relationship by portraying itself in a victim role vis-à-vis Russia as a colonial empire. While this perspective was suitable for a certain period—especially when national liberation and independence were the primary frameworks available to resist imperialist domination—such readings have run their course, overlooking these spaces’ present-day relatedness to global capitalist infrastructures of domination and cultural exploitation. Thus, it is refreshing to see a critique that highlights the continuities between postcolonial and post-socialist conditions, where ‘post’ hints not only at a space for correspondence but also at a ‘critical standpoint’ recognising divergent and overlapping experiences and struggles (Chari and Verdery, 2019).

Anastasia Sosunova’s work epitomises an affirmative critique of the shared global condition without obscuring historical and geopolitical differences. Reflecting on the curation of the bienniale, Sosunova notes, “what I liked about the Kaunas Biennial or Riga’s Survival Kit [authors comment; the third biennial taking place in parallel to Kaunas and Ljubljana] is that their shared theme referred to this weird and complex ‘everywhere at the same time’ kind of context of the globalised world, while acknowledging that every place is like ‘nowhere else’”. Their installation, Body of an Image, conceived on-site during one of the guided tours organised by the curators, drew on both archival material and fictional tools to explore the ambivalence of postcolonial and postsocialist encounters and the productive frictions they can yield. The piece drew inspiration from and referenced Vytautas Andziulis, who dug out his basement to run a secret, oppositional underground publishing house during Soviet times. Adziulis constructed a printing press from discarded Soviet machinery parts to primarily print Christian and anti-Soviet material. He dubbed it Hell’s Machine. Sosunova, in contrast, constructs their own fictional resistance machine from scrap metal pieces devoid of any nationalist and religious sentiment, instead serving as a bridge between two contemporary resistance outlets: the 1990s Lithuanian gay magazine Naglis and Uganda’s contemporary queer magazine Bombastic. Though separated by time and space, the two magazines share the underground resistance of the gay and queer movement(s). In conversation with us, Sosunova reflects on how creating this fictional machine of resistance by linking it to queer oppression allowed them to reshape history as “a friendship concretised through the postcolonial liberation”. So, by interweaving nods to similar and contradictory expressions of resistance and bringing in elements of imagination, Sosunova’s work makes us question whether we can align our distant yet connected struggles while not only acknowledging differences in historical baggage but even drawing inspiration from that to remould it into something (a)new.

Where do we go from here?

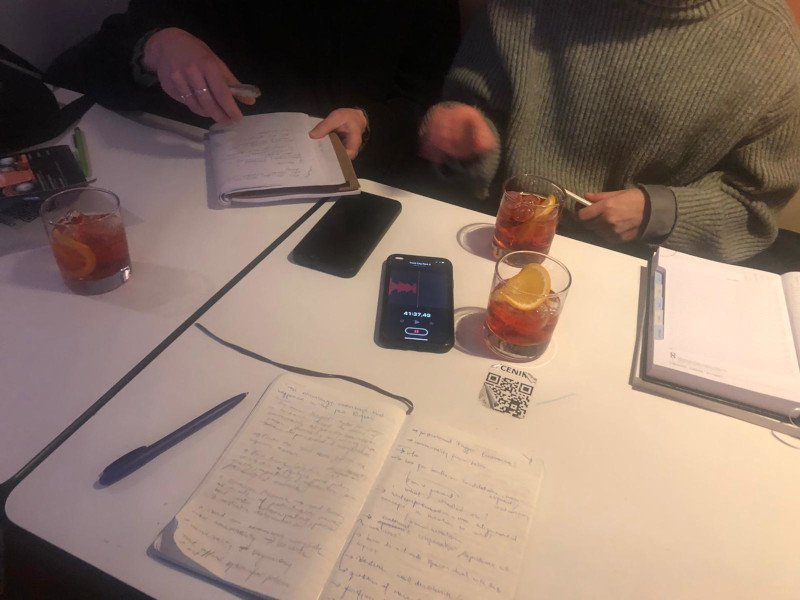

As we sipped on overpriced Negronis in the centre of Ljubljana after visiting the biennial, we had a strong sense that the edges of the capitalist world system have moved further East.Yet, the artworks at both biennials also highlight the continued power of peripheral political positions in Eastern Europe; those who navigate intersections of postcolonial and postsocialist transformations to elicit new political ideas and projects. However, two challenges remain. On the one hand, how to make those ideas actionable beyond the microcosm of the contemporary art field? And, on the other hand, how to balance the poignant quest for solidarity with productive (self)critique?

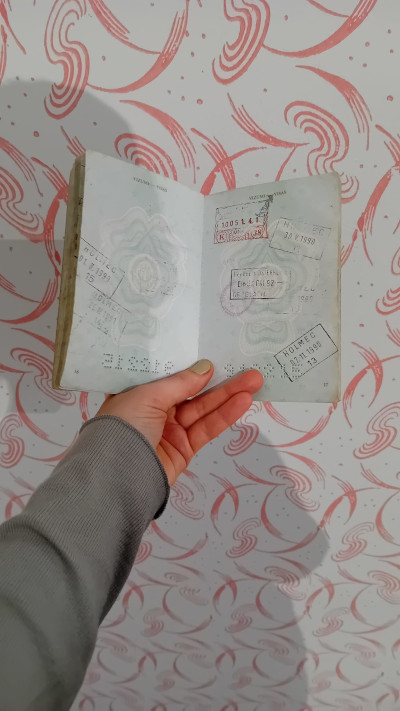

In what concerns the first challenge, the tepid response from the Eastern European art establishment, with some notable exceptions, to ongoing genocides in Myanmar, Palestine, Sudan, and elsewhere shows a failure to move from aesthetics and poetics to political praxis. As for the latter challenge, future research on similar manifestations of the relational decolonial gaze in contemporary art must be wary of not painting postcolonial and postsocialist encounters in these contexts too much as ‘events’ (Badiou, 2005), radically new occurrences that can interrupt the status quo but are detached from any historical, socio-political or economic positioning. When yet another artist from Africa or the Middle East, whose works one gets to see in European galleries at the exhibitions on decolonial futures, again fails to obtain their travel visa we should be reminded that people from the Global East and the Global South are still differently situated within the structures of racial capitalism as well unequally subjected to the violence of the global mobility regime (Van Houtum 2010).

Nonetheless, what we tried to argue here through the examples of Kaunas and Ljubljana biennials is that bringing into dialogue postcolonial and postsocialist subjects and histories seem to excavate a space for a relational decolonial gaze that can offer intersectional and multiple critiques. Instead of binary readings of white and black, coloniser and colonised, resistance or existence, such a gaze embraces the ambivalence and messiness of intersecting oppressions and multiple resistances beyond the state within the global postcolonial condition. It can cultivate new threads of solidarity with the Global South, mindful of avoiding alliances that echo the relationships of imperialism and capitalist paternalism during the Cold War.

In times when alternatives seem to have vanished (Piškur, 2024), emphasising the potential of such a relational decolonial gaze for the creation of conditions and coalitions for political imagination is especially tempting, but is ‘at best gestural if not counterproductive’ (Malik 2019) if not coupled with a reflection on art infrastructures themselves.

Julija Kekstaite is a PhD researcher in Sociology at Ghent University, Belgium, and a researcher-activist with the grassroots group Sienos Grupė in Lithuania. Her interests encompass various strands of critical theory, focusing on border violence and resistance in the post-Soviet space.

Ava Zevop was born in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia and currently lives in Brussels, Belgium. She is a visual and media artist, and an independent researcher. In her practice, she concerns herself with technological degrowth from the position of intersectional struggle, and global justice.

Soline Ballet is a PhD researcher in Social Work and Social Pedagogy at Ghent University, Belgium focusing on social work initiatives with illegalised migrants. Their interests include solidarity, migration management and governance, and power/knowledge practices.

References

Badiou, A. (2005). Being and event (O. Feltham, Trans.). Continuum. (Original work published 1988)

Chari, S., & Verdery, K. (2009). Thinking between the posts: Postcolonialism, postsocialism, and ethnography after the Cold War. Comparative studies in society and history, 51(1), 6-34.

Dražil, G. (2023). Mohammad Omar Khalil and Some Highlights from the History of the Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts. In Ohene-Ayeh, K., Haizel, K., Ankrah, P. N. O. & Kudije, S. (Eds.) (2023). From the void came gifts of the cosmos: a reader. The 35th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts. International Centre of Graphic Arts (MGLC)

Dugonjic-Rodwin, L., & Mladenovic, I. (2023). Transnational Educational Strategies during the Cold War: Students from the Global South in Socialist Yugoslavia, 1961-91. Socialist Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement, 331-360.

Ohene-Ayeh, K., Haizel, K., Ankrah, P. N. O. & Kudije, S. (Eds.) (2023). From the void came gifts of the cosmos: a reader. The 35th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts. International Centre of Graphic Arts (MGLC)

Malik, S (2019). Contemporary Art, Neoliberal Enforcer. Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ivQjEBaJh5g. Accessed 19, October 2024.

Piškur, B. (2024). Troubles with the East(s). L’internazionale Online.https://archive-2014-2024.internationaleonline.org/opinions/1123_troubles_with_the_easts/

Povinelli, E. A. (2012). After the last man: Images and ethics of becoming otherwise. E-flux journal, 35.

Van Houtum, H. (2013). Human blacklisting: The global apartheid of the EU’s external border regime. In Geographies of privilege (pp. 161-187). Routledge.

Cite as: Kekstaite, Julija, Ballet, Soline, and Zevop, Ava 2024. “Fabricating political imagination in contemporary art ‘peripheries’. Postcolonial and postsocialist encounters in Slovenia and Lithuania” Focaalblog 3 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/12/03/julija-kekstaite-soline-ballet-and-ava-zevop-fabricating-political-imagination-in-contemporary-art-peripheries-postcolonial-and-postsocialist-encounters-in-slovenia-and-lithuania/