There’s a Committee for Committees!

A few weeks ago, I received a message from a colleague. It was the sort of funny thing that one friend says to another when their most ridiculous suspicions have been proven true. It said:

“There’s a committee for the membership of committees!”

My colleague discovered this while filling out a form at the University of Cambridge that required her to declare all the committees she sits on (ostensibly to keep an eye on conflicts of interest). I had to complete the form too because I am a Trustee of the University. This means that committees play a substantial role in my working life. Too substantial in fact. As of December 2021, I sit on about 20 of them.

I spend hours per month sitting in one committee, checking the minutes of other committees that I also sit on. Sometimes I write reports that are technically addressed to myself. This is not the satisfying and intellectually curious life I imagined when I became an academic. It feels like I am trapped in an Escher picture, walking endlessly up and down a looping stairway to nowhere. So of course, there would be a Committee for Committees. That’s what happens when a university has so many committees.

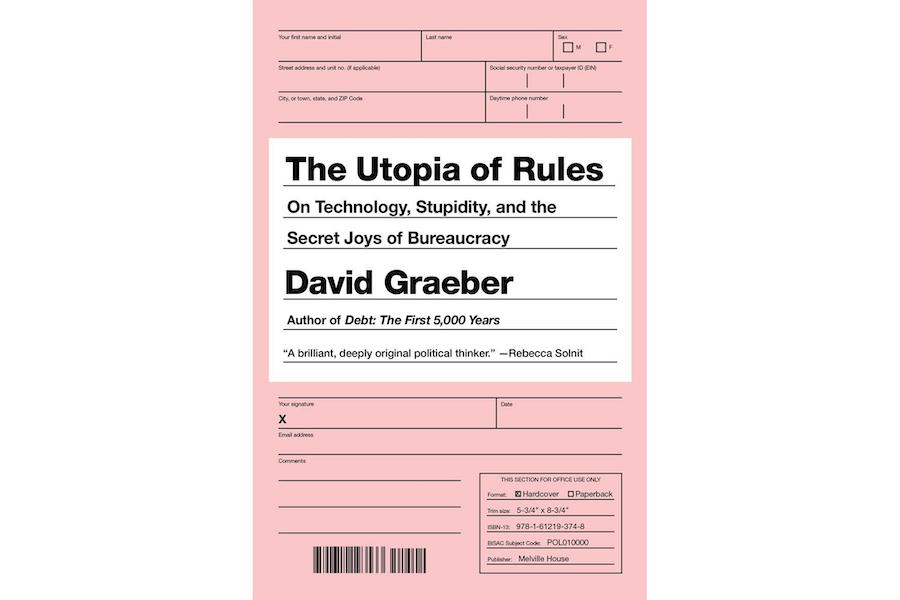

Like so many aspects of human social life, Graeber has an idea about this experience. It is an idea about that feeling of wasting your time on tasks that are not worth doing. The idea is called Bullshit Jobs (Graeber 2013, 2018). It says that most of us spend our time doing jobs are unsatisfying and serve no real purpose for society. Graeber says that capitalism has given us these jobs to keep us busy.

The Bullshit Jobs book (2018) was adapted from an essay published in Strike! Magazine (2013). One of the most memorable arguments of the essay is that there is an inverse relationship between one’s salary and the genuine social importance of one’s work. The more important you are to society, the less you get paid. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Graeber was proven correct when lockdowns prompted many nations to categorise some people as essential workers without whom society would collapse. If you had to go to work, then you were genuinely important to society. But you probably didn’t get paid a lot for being so. This maps well onto Graeber’s vision of a world of dockers, nurses, and rubbish collectors, ranged against all the management consultants and people sitting on pointless committees.

Like so much of Graeber’s work, the essay made me question why we do the things that we do. In the true spirit of anarchism, the work was destabilising. Which means that it revealed the injustice and weakness of the existing social order and showed the possibility for change. As I once heard Graeber say in a 2010 London Teach-Out shortly before a riot, ideologies of power are like the glass windows of a jewellery store. They tell you to stay in your place. But if enough people smash them, it becomes clear that they were always just glass.

The Bullshit Jobs essay was in this spirit. It was a prompt to imagine a different world, and I loved it. But when that prompt was expanded to the length of a book, it was stretched so thin so that you could see through it. I am going to talk about Bullshit Jobs by considering three things. First, whether Graeber misunderstands how bullshit tasks relate to one another in complex systems. Second, whether the thesis misunderstands capitalism’s tendency towards profiteering and the disregard for marginal populations. Finally, whether the thesis is focussed on the wrong sort of human satisfaction in work. But this is a short essay, so each issue will only be addressed briefly.

Bullshit Tasks

One of the main problems with the book was the research method, which largely rested on asking people which aspects of their work were ‘bullshit’. This is a problem, because by focusing solely on the emic experience of work, we do not necessarily understand the structural significance of that work. A person paid to guard an empty warehouse may seem to be doing a ‘bullshit job’ and perhaps it feels that way too. But the work is generative of profit for somebody else, even in an attenuated manner. In this instance that job would be integral to an opaque structure of risk assessment and insurance that dooms some of us to stand in front of empty warehouses because doing so is in the economic interest of other people. The Bullshit Jobs model tends to conflate questions of work satisfaction with those of wider structural and economic significance.

More importantly the model does not grapple with the fact that there is no necessary consistency of experience in bullshit jobs through time. The model implicitly rests on the assumption of a continuous temporal imagination of work, where satisfaction is to be had all the time or not at all. That is not how work functions. And it is especially not how bullshit, box-ticking work functions. Such forms of bureaucratic work make up a substantial proportion of Graeber’s analysis. One may spend all day checking whether a box on a form has been ticked, and it might feel pointless. But on the odd occasion where it turns out that the box has not been ticked, or where the form contains a lie… that is the moment where the value of the exercise becomes clear and a bullshit job can be socially transformative.

Imagine that you are the absurd character of a (once) working class, Marxist academic in an elite university, spending hours a week trawling through committee papers. Perhaps your soul aches with the suspicion that you are wasting your time and have sold out. Until you find an innocuous line of text tucked away in a committee paper; a text that if unchallenged would quietly remove permanent employment status from everybody in your university that changed their institutional role at any point in the future. Suddenly it seems important that somebody is there to read all these papers. And it seems especially important that the people doing the reading should not assume that the work is bullshit.

Bullshit jobs are not usually bullshit all the time. It would probably make more sense to rather talk of bullshit tasks. One should then consider whether those tasks coalesce into something more impactful, and why this is integral to the nature of complex economic and institutional action. You would be prudent to pay more attention to the box ticking bureaucrats, because even if you consider their work to be ‘stupid’ (Graeber 2015) the combined aggregate of their tasks will nonetheless shape the world around you. However, you probably wouldn’t know about it, because bureaucracy is by its very nature quiet and anonymous (Kesküla and Sanchez 2019). The transformative dimensions of much bureaucratic work are slower, and they are crucially less individualised than other types of work. But they coalesce into forms of power (Bear and Mathur 2015), and as power they can never be bullshit.

Many of Graeber’s bullshit jobs are artefacts of social complexity, and their impact is distributed at a social and temporal scale that exceeds his model. I doubt the existence of a coherent category of bullshit jobs. There is also no evidence that they exist to keep people out of trouble.

Capitalism Doesn’t Have a Committee

Modern capitalism lacks the concerted agency to create mass pointless work for reasons of social engineering. It principally strives towards the economic exploitation of mass populations, and is content to abandon those that it cannot readily exploit.

Graeber (2013) says that the only societies that used to give people pointless work were state socialist ones. They did this to redistribute wealth and keep people out of trouble. However, he argues that in the late 20th century increasing mechanisation and the shifting of production to the developing world left much of the working population in wealthy capitalist societies with nothing to do. That population was a threat to the established social order, and needed to be given bullshit jobs to distract them and tire them out.

This claim is incorrect. Neoliberal capitalism doesn’t have a committee. It certainly doesn’t have the type of committee that engages in a coherent global endeavour to stop us from sliding into thoughtful idleness. Some people would like to believe that neoliberalism doesn’t exist at all and is only conjured into being by left wing social scientists. Those people are wrong. There are explicit packages of policies, reforms, professional networks, and ways of looking at the world that make neoliberalism a real thing. But still, neoliberal capitalism does not have a committee.

I appreciate anthropological attention to the discursive and moral life of neoliberalism, and I have written about how neoliberal actors may feel that they are doing good in the world (Sanchez 2012). However, for a structural analysis like Bullshit Jobs what matters is the core motivation of capitalism, which is profit. The notion of a world of pointless employment that does not exist to make money, simply does not fit with what we know about most of economic life. More broadly, there is the lingering issue that capitalism is untroubled by the fact that plenty of people in wealthy societies have not been given pointless work.

If I can be permitted to stick with the anecdotal style of Bullshit Jobs here is an example to illustrate my point: I was raised on a British council estate where a good proportion of people were completely without any form of work. Some tended to get into trouble, and aged into lives where they harmed themselves and others. Feasibly, those populations could be imagined as a threat to social order. But the Committee was untroubled by that possibility. Capitalism was happy for our family to live on state benefits for years, treading water below the poverty line, sliding into depression and violence. Although the hateful notion of a ‘Chav’ underclass would suggest otherwise, people in those environments often have critical perspectives on how the world works. And sometimes they try to do something about it. It was in just such an environment that I was radicalised as a young teenager, and grew into the person writing this essay. This personal example is perhaps a little cloying. But the fact remains that there are too many people left behind by the Bullshit Jobs Committee, for the idea to make sense.

Or less anecdotally we might consider populations at the acute end of the social marginality spectrum, those apparently expelled by capitalism as if they are somehow worthless, condemned to lives of floating marginality, living in refugee camps or prisons, standing by the road at labour markets waiting for a gig that never comes (Sassen 2014). It is mistaken to see such populations as lacking in creativity and will (Alexander and Sanchez 2019). It is also mistaken to not recognise them as sources of economic value for capitalism. Bourgois’ (2018) work on predatory accumulation shows this, as does older thinking on the Prison Industrial Complex. It turns out that those allegedly dangerous populations are still worth something to somebody. If this were not so, then marginalised communities would not be beset everywhere by landlords, credit agencies, racketeers, brokers, and for-profit providers of social and justice services.

Capitalism has not found ways of giving dangerous populations bullshit jobs to keep them out of trouble. Rather, capitalism is all too often immune to the trouble that they might cause, and indeed routinely finds them to be a useful area of exploitation.

What Isn’t Bullshit?

When Bullshit Jobs discusses how people feel about their work, it rests on Graeber’s theory of value, where action that is meaningful is that which is socially productive. I am a fan of Graeber’s theory of value. But his reconfiguration of it for a discussion of work tasks is not quite right. For Graeber, work is socially productive principally when it cares for the world. I believe that this idea is trained at the wrong level of action. The ability for one’s work to ‘care’ might be better conceived as just one expression of the ability to transform the world.

As I have argued elsewhere (Sanchez 2020), the single most important factor in peoples’ determination of satisfying work is an engagement with processes that make demands on one’s ability to affect change upon the world. Put simply, people like work that challenges them to alter something, be it the material form of an object, the value of a commodity, the dispositions of other people, or the skills and capacities of themselves. Troublingly, transformative work does not map onto ‘caring’ and some people may find it enjoyable to do impactful things that harm others. More broadly, transformation is not restricted to an impact on human relations, or a lasting contribution to social life.

I have spent my working life talking to people about their working life. And because I am an enthusiast, I tend to do this even when I am not ‘working’. My experience is that there are many jobs that I would find pointless to do myself, but which other people do not. That is because they have found a meaningful transformative dimension in their work that would elude me, and they therefore find it satisfying to manage IPOs, trade stocks, or write advertising copy. The transformative action of work needn’t happen in an instant. And indeed, it often takes lots of people to make it happen at all. People are smart enough to know this, which is why the daily grind of bullshit tasks does not necessarily translate into a wholly bullshit job. Every now and again, the box hasn’t been ticked properly, and it matters.

Conclusion

I think that Bullshit Jobs is basically wrong. Nonetheless I like the fact that a book like this exists, and I wish that there were more of them.

Anthropology is often mired in citations and pedestrianism. Or else we are that other type of Anthropologist (my least favourite): the one mired in pretentious, performative theorising. As a consequence, we are a discipline that often struggles to say anything original and of wider social significance. But in Bullshit Jobs we have a work that is imaginative, fun to read, and about issues that most people can relate to. It is the voice of a man speaking to the reader not as an academic showing off or trying to intimidate you, but as though he had met you at a party, and you were lucky enough to be chatting to somebody that really made you think.

That’s what I love about Graeber’s writing; the essential humanity of it. His work conveys the mind of a person that cares enough to look at things that matter to everybody else, and who cares enough to speak about them in a way that is exciting and intelligible. Even when Graeber was wrong, he made you think. And what he made you think about was invariably something important. That’s what an academic is for.

Andrew Sanchez is Associate Professor in Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. He has published on economy, labour, and corruption, including Criminal Capital: Violence, Corruption and Class in Industrial India, Labour Politics in an Age of Precarity co-edited with Sian Lazar, and Indeterminacy: Waste, Value and the Imagination co-edited with Catherine Alexander.

This text was presented at David Graeber LSE Tribute Seminar on “Bullshit Jobs”.

References

Alexander, C. & Sanchez, A. (eds). 2019. Indeterminacy: Waste, Value and the Imagination. Berghahn

Bear, L. & Mathur, N. 2015. ‘Introduction: Remaking the Public Good’ The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 33(1): 18–34

Bourgois, P. 2018. ‘Decolonising drug studies in an era of predatory accumulation’ Third World Quarterly, 39(2): 385-398

Graeber, D. 2013. ‘On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs: A Work Rant’ Strike! 3

Graeber. D. 2015. The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. Melville House

Graeber, D. 2018. Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. Allen Lane

Kesküla, E. & Sanchez, A. 2019. “Everyday Barricades: Bureaucracy and the Affect of Struggle in Trade Unions” Dialectical Anthropology 43(1): 109-125

Sanchez, A. 2012. ‘Deadwood and Paternalism: Rationalising Casual Labour in an Indian Company Town’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18(4): 808-827

Sanchez, A. 2020. ‘Transformation and the Satisfaction of Work’ Social Analysis 64(3): 68-94

Sassen, S. 2014. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Harvard University Press.

Cite as: Sanchez, Andrew. 2022. “Work is Complicated: Thoughts on David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs.” FocaalBlog, 4 March. https://www.focaalblog.com/2022/03/04/andrew-sanchez-work-is-complicated-thoughts-on-david-graebers-bullshit-jobs/