When the daily Miami-Santiago de Cuba flight landed in Cuba in May 2024, a passenger at the back of the plane shouted in Spanish: !Ya llegaron los dolares! “The dollars have arrived!” Everyone on board started laughing and clapping. In making that announcement, the Cuban passenger referred to the fact that visitors to Cuba were the main suppliers of hard currency on the island. It is extremely cumbersome, if not impossible for Cubans to exchange Cuban pesos to US dollars in official banks or in exchange offices. As a result, US dollars are effectively accessible only through the illicit market, fueled by foreign currencies entering the island thanks to travellers. In shouting that “the dollars” had arrived on the tarmac, the passenger also pointed to how everyone is looking for dollars in the hope of better life conditions. This vignette further speaks to the recent inflation phenomenon in Cuba, since the increased demand for foreign currency in the illicit market, caused by recent internal economic reforms, has created more inflation, subsequently deteriorating the value of the national currency (Truebas Acosta 2023).

We experienced this anecdote and many others similar to it while conducting fieldwork and teaching two ethnographic field schools during Summer 2023 and Spring 2024 in Santiago de Cuba. These stories, often full of sarcasm and humour, describe what the anthropologist Myriam Amri calls “inflation talk”, which she defines as “a mode of small talk that operates as critique and affect” (2023:29). “Inflation talk” further refers to anecdotes, jokes, conversations but also, as Amri shows, the sensorial experiences that relate to how inflation is lived every day. Stories also express how people cope with an “inflation bomb”, a term suggested by national economists to characterize the recent and ongoing inflation in Cuba.

The extreme escalation of prices in Cuba since 2021 is on everybody’s lips, generating anxiety and despair. In this blog, we engage with the following questions: how are Cubans responding to the current economic crisis? and, how do they respond to inflation rates while facing a complex economic system that is failing them? We use the increase of the price of eggs as a case study to explore how inflation is lived and dealt with every day. We investigate the phenomenon of inflation through the lense of pressure. Wiegratz, Dolan, Kimari, and Schmidt (2020) argue that pressure emerges at the convergence of “overarching ideology, economic structures, social webs of exchange, and the dynamics of capitalism,” and that pressure is the result of a disbalance between the reality of what people imagined being able to fulfill and the real economic burdens of their daily life. We argue that pressure allows for an in-depth understanding of the connections between how people live and how they strive to develop coping mechanisms to face pressure.

Inflation a lo Cubano

Based on their own data, the Cuban government reported an inflation of 77 per cent in 2021 and 39 per cent in 2022 (Estudios Economico de América Latina y el Caribe 2023). Other sources show more drastic figures. Cuban economists Pavel Vidal and Luis R. Luis (2024) report a “big-bang devaluation of the peso in 2021” with inflation rates ranging from 174 per cent to 700 per cent that same year. Such extreme figures reflect more accurately the increase of prices that were reported to us by Cubans. Inflation in Cuba is not characterized by a steady increase observed over a certain period. It corresponds to sudden inflation, and monetary instability, caused by a long stagnant economy, Donald Trump’s strict sanctions towards Cuba, the Covid-19 pandemic, and a failed economic reform (referred to as ordenamiento económico: money ordering). As a result, Cuba is undergoing its worst economic crisis in contemporary history; more than one million Cubans have left the island since 2021 in what is known as an unprecedented exodus.

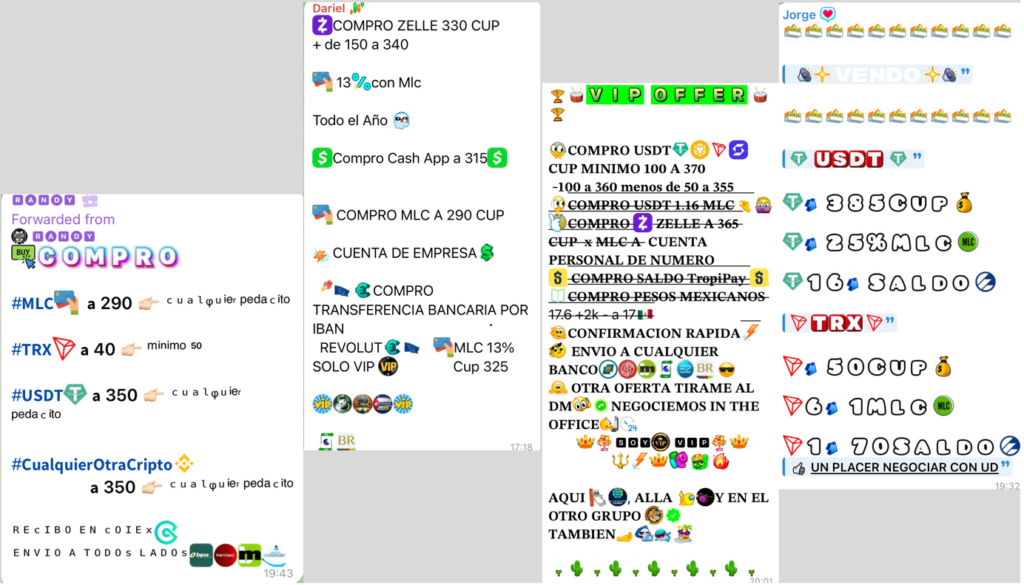

In Cuba, the exchange rates between the Cuban pesos and the US dollar follow the rules of the informal sector. Rates are shared through internet communication technologies, mainly WhatsApp. Since 2022, the Cuban government exchanges Cuban pesos for US dollar at the fixed rate of 120 pesos to 1 US dollar. On the informal market, rates oscillate responding to supply and demand. As we write these lines, the exchange rate is approximately 310 pesos to 1 US dollar in Santiago de Cuba, and 320 pesos to 1 US dollar in Havana, according to local sources. In short, and as suggested by our opening vignette, nobody exchanges US dollars at the bank except tourists. To know the current informal exchange rate, Cubans join WhatsApp groups in which sellers and venders share their rate and how much money they wish to exchange.

In addition to accessing information about exchange rate tendencies on WhatsApp, Cubans also consult elTOQUE, an online platform which provides information about a broad range of topics, from music and literature to the oropouche epidemic ravaging Cuba. elTOQUE is associated with the Observatorio de Monedas y Finanzas de Cuba (OMFi: The Cuban Currency and Finance Observatory) led by Pavel Vidal, an economist who worked for the Cuban Central Bank but who now resides in Colombia, and Abraham Calás, the director of development of elTOQUE website. The site provides the daily exchange rate in the informal sector as well as analysis about the evolution of economic and financial indicators. As explained on the site, the OMFi monitors prices and other data related to remittances, using algorithms that they collect through online sales of currency. elTOQUE has become the reference for Cubans on the island and in the diaspora who wish to get the pulse of the daily exchange rate in Cuba (note that elTOQUE figures do not account for local variations). The site is not based in Cuba and is not approved by official Cuban authorities.

Eggs as indicator of inflation

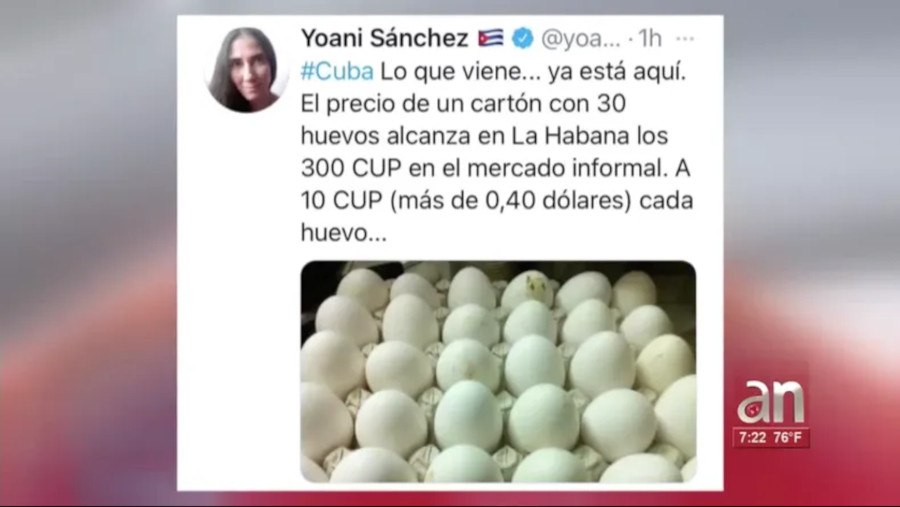

In Cuba, the popular saying “Aqui todo cuesta un huevo” (Here everything costs an egg) is a way of criticizing the exorbitant prices of consumption products. Eggs are scarce, and when Cubans can find some, they are inaccessible because of their prices. In Fall 2024, the price of a carton of 30 eggs is oscillating between 3,000-4,000 Cuban pesos, close to the 5,000 pesos basic monthly salary of a family medical doctor. In recent years, complaining about the escalating price of eggs has become a reference point to discuss inflation and the harshness of life. For instance, the famous blogger Yoani Sánchez complained on Twitter that the price of a box of a carton of 30 eggs was 300 Cuban pesos. That was in 2021 (see image 1).

In April 2024, the price of the same carton reached 3,500 Cuban pesos, a monthly salary for a state worker (see image 2). These figures are hard to imagine for people living outside Cuba. How can a monthly salary cover only the price of a 30 eggs carton! When the monetary re-structuring was implemented in January 2021, the government adjusted positively the salaries in the state sector (covering a large portion of the population), pensions and social assistance. However, wage increases without adequate supply of goods provoked inflationary pressures (Truebas Acosta 2023).

In addition to the eggs, other proteins are often used as reference to inflation. The price of chicken often comes up in casual conversation. Queli, a cultural worker with a BA degree, is paid 4,5000 Cuban pesos per month. She told us that the day she received her monthly salary, she went to a local mipyme (a small grocery store privately owned) to buy 4 pounds of chicken which cost her exact salary. “We are going to eat chicken for a few days,” she shared with us, “but what about the rest!” she laughed sarcastically. Eggs and other protein products often serve to express the sense of despair associated with the current economic crisis. To collect the most up to date figure of the price of eggs in Cuba to write this blog entry, we sent a message on WhatsApp to a friend in Santiago de Cuba. He quickly responded: “Prices are crazy, easily 3,000 pesos for an egg carton, if you are lucky enough to find one. […] It’s so bad right now, I didn’t eat today, and I had to send my two daughters to the neighbour’s house [who could give them something to eat], it’s so painful.”

Until recently, the Cuban food rationing system sold 5 eggs per month to each Cuban. The price of eggs in the official ratio system remains stable and affordable. According to our data, the price of eggs increased by less than 0.01 US dollars between 2019 and 2024, a huge contrast with the informal economy sector, on which Cubans must rely in order to survive. The problem on the official and subsidized market is not cost, but scarcity. At the time of writing this blog entry, Cubans in Santiago de Cuba had not received any eggs through the official rationing system for the last 8 months. And the scarcity of eggs, and other products distributed through the official system is rampant all over Cuba; it is not a local problem.

Inflation as pressure

In 2005, Fidel Castro distributed 100,000 pressure cookers to Cubans as a response to the growing energy crisis, and to “reassert control over the nation’s economy.” The image of Cubans receiving pressure cookers offers a telling metaphor. Valves of pressure allow tensions to escape, at least momentarily, as frustrations towards periods of shortages grow. Cubans have lived under pressure almost permanently, or as Kapcia (2008) would argue, in a “permanent cycle of crises.” They have learned to luchar (struggle), to resolver (resolve), and to inventar (invent) ways to cope with the shortage of products and information, among other things. Inflation talk Amri argues “bring(s) together atmosphere and affect” or a “sense that something is in the air” (2023:39). In Cuba, economic tensions weight heavy in the air.

As mentioned, Cubans respond to inflation in various ways, sometimes in telling stories and jokes. But tensions are also embodied. Elsewhere, we argue that different forms of pressure (air, atmosphere, and economic) allow for grassroots (i.e. ethnographic), spontaneous and nuanced understanding of how an accumulation of tensions shapes bodies in moments of crisis (Boudreault-Fournier 2023). Inflation generates anxieties as people face serious material constraints and pressure provides an opportunity for exploring the ways in which people cope, deflect and deal with signs of pressure. Stress and anxiety caused by high pressure (systemic, economic and political) bend bodies in painful ways until they escape, they morph into another shape, or until they explode. To decompress, some Cubans take medical drugs, while others adopt meditative practices, cultivate medicinal plants or join religious groups. Hypertension caused by stress and lifestyle (i.e too much pressure), remains undertreated in Cuba, because of medication shortages (Rojas et al. 2019). This unbearable pressure pushed more than one million Cubans to leave the island in less than three years.

The current economic crisis leads to an increase of pressure. The current situation is worse than the Special Period in the 1990s, an economic crisis caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union, that left older generations traumatized. Cubans face unprecedented shortages of fuel and daily long blackouts, in addition to lack of food. The recent economic reforms implemented at the beginning of 2021 combined with other measures adopted by the government to attempt to stabilize the economy, to face serious problems of shortages and to respond to an infrastructural and energy crisis contribute to deteriorating health and life conditions for the Cuban population.

Conclusion

We have conducted fieldwork in Cuba since the year 2000. During our recent trips in 2023 and 2024, we observed a striking loss of confidence towards the government and an unprecedented level of dissatisfaction in comparison to pre-Covid time. The participation of Cubans in the illicit market which dictates the exchange rate suggests a clear transfer of confidence to the informal economy. Conversations about inflation in the street, on social media and through communications technologies show how Cubans have found a space in which they can more actively participate in the Cuban economy, reminding us of the agency of the public in monetary affairs (Holmes 2023). Even if the situation is extremely harsh, and even if many have lost hopes for a better future in Cuba, the informal economy offers Cubans a pressure valve to cope with difficult life conditions and to take action. That is, until the pressure goes up again.

This text is part of the feature The Social Life of Inflation edited by Sian Lazar, Evan van Roeckel, and Ståle Wig.

Alexandrine Boudreault-Fournier is an Associate Professor at the University of Victoria. Her research interests include media infrastructure, sound, electronic music, digital data consumption and circulation in Cuba. She wrote the book Aerial Imagination in Cuba: Stories from Above the Rooftops (2020), and co-edited the volume Audible Infrastructures: Music, Sound, Media (2021).

Mélissa Gauthier is based at the University of Victoria. She specializes in economic anthropology and border studies with particular attention to the interplay between state and society occurring via informal markets. Her work is based primarily along the Mexico-United States border and in Yucatán, Mexico.

References

Amri, M. 2023. Inflation as Talk, Economy as Feel: Notes Towards an Anthropology of Inflation. Anthropology of the Middle East, 18(2), 27–45.

Boudreault-Fournier, Alexandrine. 2023. “Under Pressure: Catching the Pulse of a Cuban Crisis.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 41(3): 392-412.

Estudios Economico de América Latina y el Caribe. 2023. Cuba. Cepal org. https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/3392278d-b1b7-46de-b047-b0c0d6aa11a9/content

Holmes, D.R. 2023. “Quelling inflation: The role of the public.” Anthropology Today 39: 6-11.

Kapcia, A (2008) Cuba in Revolution: A History Since the Fifties. London: Reaktion Books.

Rojas, N A et al. 2019. “Burden of Hypertension and Associated Risks for Cardiovascular Mortality in Cuba: A Prospective Cohort Study.” Lancet Public Health 4(2): E107-E115.

Truebas Acosta, Sergio. “Inflation in Cuba: An Analysis from the Perspective of the Main Nominal Anchors of Monetary Policy.” International Journal of Cuban Studies. 2023. Vol. 15(2):175-202.

Vidal P, Luis LR. 2024. “Cuba’s Monetary Reform and Triple-Digit Inflation.” Latin American Research Review. 59(2):274-291. doi:10.1017/lar.2023.59

Wiegratz J, Dessie E, Dolan C, Kimari W. M. Schmidt. 2020. “Pressure in the City.” Development Economics Blog. Available at: https://developingeconomics.org/2020/08/17/blog-series-pressure-in-the-global-south-stress-worry-and-anxiety-in-times-of-economic-crisis/

Cite as: Boudreault-Fournier, Alexandrine and Gauthier, Mélissa 2024. “Inflation as pressure: coping mechanisms from Eastern Cuba” Focaalblog 10 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/12/10/alexandrine-boudreault-fournier-and-melissa-gauthier-inflation-as-pressure-coping-mechanisms-from-eastern-cuba/