kolaya (a Ravi Varma painting could be observed on the adjacent right wall), photo by T.P. Bineesh

Communism continues to thrive both as a ubiquitous presence and a powerful electoral force in the south Indian state of Kerala. Established in 1940, the Communist Party of Kerala formed the first democratically elected government of the state in 1957. By organizing popular movements which demanded the abolition of feudalism, landlordism, and the transfer of land to its tillers, the Communist Party gained a strong foothold amongst the masses and built a solid base in rural areas from where it could not be dislodged (Fic, 1970). Today, the communist movement in Kerala, especially as represented by its dominant party, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)], can be said to display tendencies of populist movements, including a cult of a leader-hero and the rhetoric of a ‘pure people’ versus the ‘corrupt elite’ (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2017).

This blog looks at the perpetuation of the leader cult in Kerala through the use of commemorative portraits. Disseminated through domestic and digital spaces, these images reinforce a sense of collective identity among party workers while also invoking filial sentiments. I will be reading such negotiations utilising the idea of corpothetics or corporeal aesthetics which concerns the mobilisation of all senses for the appreciation of a text (Pinney, 2004). The concept is utilized appositely to understand the filial mode of reverence, effected by everyday embodied practices which enhance the affective potential and emotional capital of the Party. Such engagements, which are sensory/sentimental in character, play a key role in embedding the Party as an affective presence (rather than an abstract political programme) within the state of Kerala.

Portraits and Corpothetic Engagement

A discussion of the portraits of communist leaders hung in Kerala houses is necessary to properly situate the cultural context in which digital iconography is circulated and made meaningful. The part of the house which opens to the front yard is usually an open space (called kolaya or sit-out), which in many Kerala houses serves as a display area for objects such as family photographs, trophies, photos of Gods and ancestors, and other decor items, expecting public appreciation (see image 1).

The portraits of former Communist leaders are hung in the houses of party supporters in the kolaya. The kolaya thus functions as a private sphere communicating the family’s socio-cultural inclinations, ideologies, and aspirations. With their fixed frontal stance, these images can initiate an embodied interaction with the beholder, whose eye here functions not only as an organ of vision but also of touch. This notion could be explicated further by discussing how the mutuality of vision and its ensuing tactility was deployed in early mythological films. The devotee in such films would beseech the deity to interfere in moments of pain and distress. The dialogue that transpires between the two of them is cinematically represented through intermittent shots that show the eyes of the devotee and the deity. Sometimes even a ray would pass from the deity’s eye to that of the devotee, thereby liberating her/him from their suffering. Thus, within the Indian context, the eye is more than an organ of vision but also of touch (Pinney, 2004). The emotional resonance evoked by these portraits is to be contextualized in this corporeal visual culture.

In his study of family photographs in Kerala, Sujith Kumar Parayil (2014) demonstrates that apart from documenting the family, these photographs function as performances of the interpersonal and intimate relations between family members while also displaying their cultural capital (Parayil, 2014). He also notes how these families have a penchant for displaying the portraits of ancestors or deceased family members along with deities, thus enabling a corpothetic performance of commemoration (see image 2). Such a display is rendered corpothetic when the beholder engages with the photographs through everyday practices such as dusting, garlanding or lighting a lamp in front of the portrait.

In the Malabar region of north Kerala, where Communism emerged and continues to flourish as a formidable force, portraits, found in both Dalit and upper caste households, are often placed along with photos of Gods or ancestors, functioning as surrogates for what they represent. The portraits displayed include regional and international male leaders of the Communist movement such as E.M.S. Namboodiripad (the first chief minister of Kerala), P. Krishna Pillai, Joseph Stalin etc. along with other local leaders and ‘martyrs’ (images 1 and 2).

The reverence and admiration directed towards these portraits by the family members are performative in character, demonstrating their loyalty and affiliation towards the Party. . For instance, in image 1 the family members of the Communist family home are observed sitting in the kolaya to commemorate the ‘martyr’ Azhikodan Raghavan. A portrait of former chief minister E. M. S Namboodiripad could be seen in the background, as displayed in the kolaya. The choice of the family members to pose in the kolaya was not accidental but can be seen as a conscious decision to affirm the family’s affiliation as supporters of the Communist Party. Such transactions empower the images to exert a corrective moral eye while the visible presence of the ancestors coerces the family members to adhere to the norms and morals encoded within the family. Actions like placing the Communist portrait at a crucial spot (veranda, living room, and dining room) along with portraits of family elders (image 2) while ensuring adequate visibility, also guarantee the quotidian yet affective commemoration of the Communist movement.

Communist Iconography in Social Media

Social media plays a crucial role in determining the arc of Indian politics. It played a pivotal role in facilitating the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) victory in the 2014 elections (Kanungo, 2015). A recent example would be Rahul Gandhi’s strategic choice to engage with social media vloggers and YouTubers instead of relying solely on mainstream media during his “Bharat Jodo Yatra” (Unite India March 2023).

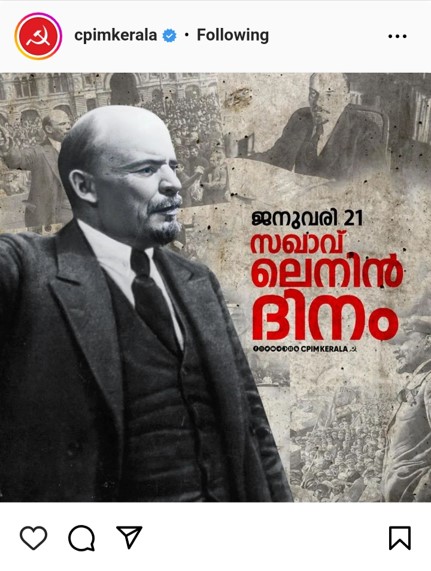

The situation is no different with Communist parties in Kerala, with the Communist Party of India (CPI) and especially the Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)] that has been active on social media since 2016, following the example set by other political parties. The integration of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp into the official communication stream of government administrative institutions would be an example. However, Party officials also utilize social media to disseminate iconography in an attempt to cultivate a digital populist style. These iconographic artifacts include posters and reels which glorify the leader while foregrounding the participatory politics of the Party. An example is image 3, posted on Instagram, commemorating Vladimir Lenin by superimposing his image over a couple of other photographs where he is seen as addressing the masses or leading them on a strike. Circulated in the form of posts, tweets and stories, such expressions intensify the affective potential of left populism in Kerala while also validating its democratic appeal among the people.

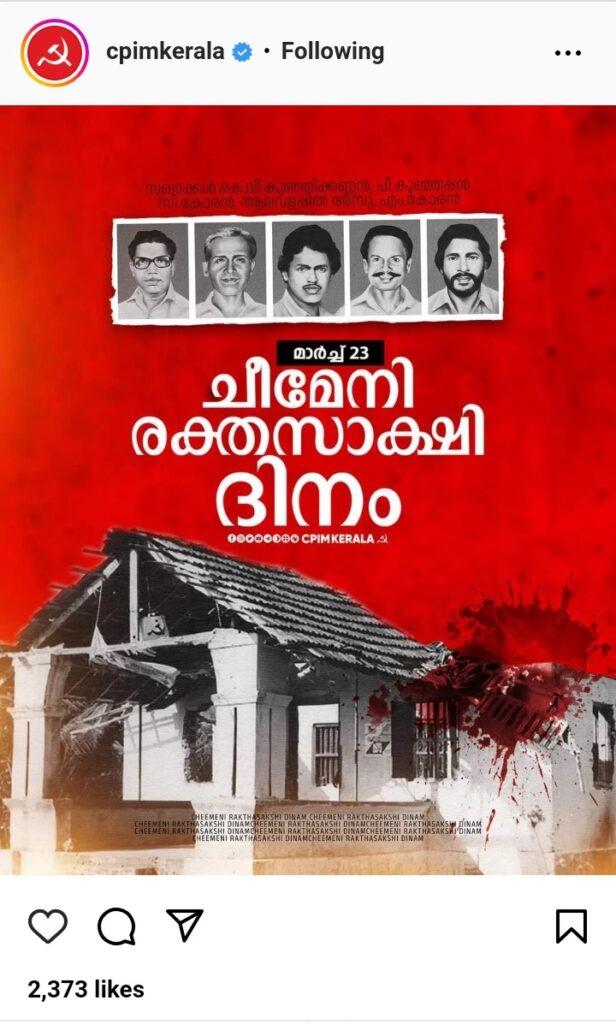

These digital images also function as counterparts to the portraits discussed in the previous section. Digital posters of the Party are suffused with captions, images of a red sickle and hammer, red festoons, Party flags, etc. Image 4 is a poster commemorating the Cheemeni massacre, where five CPM members were killed by Congress workers on March 23rd1987, at the Cheemeni Party Office of Kasaragod district in Kerala. A notable aspect of this poster is how the Cheemeni Party Office, the site of the massacre, is foregrounded. With portraits of ‘martyrs’ placed on top, the image of the dilapidated Party office superimposed with a blood splash triggers associated memories of the massacre. Such a representation effectively tweaks the images’ affective value and ensuing ‘stickiness’ – that is the way in which emotions and feelings get attached to particular objects, situations, or people, influencing one’s perception and interactions over time (Ahmed 2004).

Portraits of leaders are also circulated in similar fashion after including certain extensions. An example would be an Instagram post (image 5) featuring the image of E. Balanandan, former MP, Politburo member, and secretary of the CITU (Centre of India Trade Unions). Commemorating the death anniversary of the veteran Communist leader, the poster bears a portrait of Balanandan with other iconographic artifacts in the background, such as the Communist flag and red festoons. Further, it is accompanied by a caption elaborating on the leader and his contributions to the Party. When added to the portrait, such stylizations become corpothetic as they are implemented through actual tactile engagement with the image which entails a mere swish of the finger.

Such modifications could be read as digital articulations of corpothetic practices which until then were directed towards actual photographs. Such gestures are further amplified through actions such as commenting, sharing, and liking which has an ability to “strengthen the shared affective and political meaning-making in the community” (Hokka & Nellimarkka, 2020, 3).

The Party in everyday life

These novel forms of Communist iconography with their interactive features, invoke a new form of digital populism that requires to be performed online. Youngmi Kim (2008, 122) defines digital populism as a new type of political behaviour marked by the political use of the internet as a form of political participation as well as an instrument of mobilisation. Actuated through individualized engagements, this virtual replication of proximal empowerment (Pinney, 1997) comes across as a performance of self within the digital world. It is this performance that Schechner calls a form of public dreaming (qtd. In Papachirissi 2003, 98).

The participatory aspect of digital populism facilitates engagement of the people with the communist movement without being restricted by the constraints of formal Party lingo ridden by rigid theoretical diction. Udupa et al. (2019) highlight the significance of colloquialism in such digital interactions. Communist Parties in Kerala employ region specific and colloquial cultural references in social media. Such expressions of digital populism, which incorporate the rhetoric of the popular, facilitate the transcendence of the Party from the realm of the political to that of the affective. Nested in one’s day-to-day life, these artefacts found both in domestic spaces and social media, are crucial towards rendering the Party quotidian.

Anagha Anil is currently a PhD scholar in Cultural Studies at Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Karnataka, India. Her research focuses on the corpothetics of communist iconography in contemporary Kerala. Her research interests include visual studies, popular culture and film studies.

References

Ahmed, S. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22, no. 2: 117-139.

Fic, V. M. 1970. Kerala Yenan of India – Rise of Communist Power 1939-1969. Bombay: Nachiketa Publications.

Hokka, J. and Nelimarkka, M.. 2019 “Affective Economy of National-Populist Images: Investigating National and Transnational Online Networks through Visual Big Data.” New Media & Society, 1-23.

Kanungo, N. T. 2015 “India’s Digital Poll Battle: Political Parties and Social Media in the 16th Lok Sabha Elections.” Studies in Indian Politics 3, no. 2: 212–28,

Kim, Y. 2015 “Digital Populism in South Korea? Internet Culture and the Trouble with Direct Participation” in Digital Activism in Asia Reader, eds. N. Shah, P. Purayil Sneha and S. Chattapadhyay. Milton Keynes: Meson Press. Pp:13-126.

Mudde, C. and Kaltwasser, C. R. 2017 Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford; New York, Ny: Oxford University Press.

Parayil, S. 2014. “Family Photographs: Visual Mediation of the Social.” Critical Quarterly 56, no. 3 :1-20.

Pinney, C. 2004. Photos of the Gods: Printed Image and Political Struggle in India. London: Reaktion Books.

Pinney, C. 1997. Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Udupa, S., Venkatraman. S., and Khan, A. 2020. “‘Millennial India’: Global Digital Politics in Context.” Television & New Media 21, no. 4: 343-359

Cite as: Anil, Anagha 2024. “Portrait Populism: On the Communist Iconography of Kerala” Focaalblog 26 June. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/06/26/anagha-anil-portrait-populism-on-the-communist-iconography-of-kerala/