Sindre Bangstad: The IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism and Academic Freedom

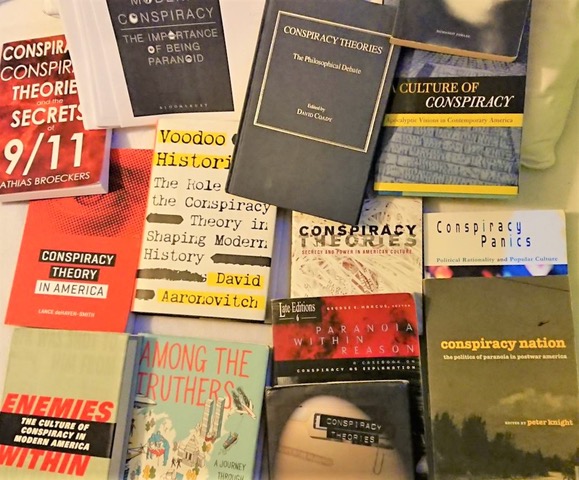

Image 1: The reinstated Gaza Solidarity Encampment at Columbia University, 23 April 2024. Photo by Abbad Diraneyya. Cancelling Mbembe On June 6 2024 I was present in the grand hall that is the University Aula of the University of Bergen in Norway when my friend Achille Mbembe received the prestigious Holberg Prize from the University… more...