At the heart of Buenos Aires lies the lovely Calle Florida. The experience of walking through this street that is exclusively dedicated to pedestrians was anything but lovely though since in the one kilometer from one end to the other I was besieged—albeit politely–by some 200 men and women barking, “cambio, cambio,” competing to give me the most pesos for my dollars.

It’s a seller’s market, with the “Benjamins,” to use the term popularized by US Congressman Ilhan Omar’s term for 100 dollar notes, especially valued. When I began my walk at one end of the street, I was offered 1100 pesos to the dollar; by the time I reached the other end, the offer had climbed up to 1400. The online price that morning was 963 pesos. I thought I had a good deal, but an Argentine friend later told me I could have done better.

The Argentine Disease

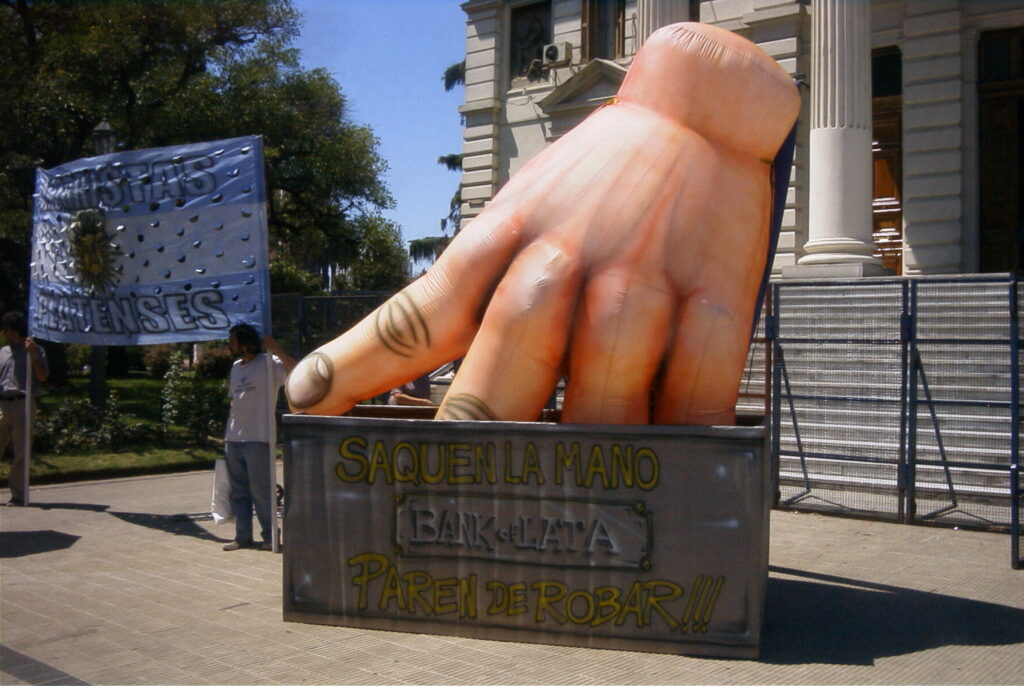

The daily depreciation of the peso relative to the dollar is a key indicator of inflation, which everyone says is the country’s prime economic problem. The conventional analysis is that the uncontrolled rise of prices stems from the government’s equally uncontrolled printing of pesos to cover its budget deficit. Thus the peso has lost its function as a store of value, forcing people to resort to the black market for dollars. With the private sector hoarding dollars and international creditors hesitant to lend owing to Argentina’s having defaulted on its $323 billion sovereign foreign debt in 2020, tourists have become a prime source of dollars for ordinary Argentines and small and medium enterprises.

The inflation rate for 2023 was over 211 per cent. This was not in the order of the 3,000 per cent annual inflation rate in 1989 and 1990, but as in that earlier period, inflation has resulted in the coming to power of regimes touting radical stabilization policies. In the 1990’s, Carlos Menem, the populist Peronist turned neoliberal, famously imposed, among other stringent measures, the 1:1 peso to the dollar exchange rate. The experiment led to chaos, with the country declaring itself unable to service its sovereign debt in 2001. Last November came the turn of the self-described “anarcho-capitalist” Javier Milei, who has promised not only to make the dollar the medium of exchange in place of the debauched peso but to also lop off off whole ministries of government and thousands of government jobs. His controversial but winning image during the November 2023 elections was his going around with a chainsaw to symbolize his determination to radically slim down government, which he regards as a “criminal operation.”

The question on everyone’s mind is, will Milei succeed where previous regimes failed?

Milei Wields His Chainsaw

Milei has been less than a year in office, but he has taken his chainsaw to the government, as he promised. He chopped off half of the government ministries, devalued the peso by 50 per cent, and slashed fuel subsidies. That was just the beginning. In the teeth of bitter opposition in Congress and in the streets, he got his “Bases Law” passed, which would allow him to roll back workers’ rights, provide tax incentives to foreign investors in extractive industries such as mining, forestry, and energy, reduce the tax burden on the rich, and provide him with the power to declare a one-year state of economic emergency that would give him special powers to disband federal agencies and sell off about a dozen public companies. In order to get the Bases Law through Congress, Milei has postponed his plans to adopt the dollar as the national medium of exchange and “blow up” the Central Bank, as he puts it, deliberately invoking an image associated with Khmer Rouges’ destruction of the Central Bank of Cambodia when they came to power in the late 1970’s.

As anticipated, the austerity measures are leading to the contraction of the economy, with the International Monetary Fund, which has signalled its approval of Milei’s policies, expecting a 2.8 per cent decline in GDP 2024. Still, according to some polls, his approval ratings are above 50 per cent. “This shows that despite suffering in the short term, the people are willing to give the president the benefit of the doubt,” said the Argentine ambassador who gave me an unexpected 45-minute briefing when I claimed my courtesy visa to visit the country. Others, like radio personality Fernando Borroni, assert the president’s popularity ratings reflect not no much approval of him as rejection of the failed policies and personalities of the past.

Javier and Karina

Milei is perhaps the most colorful and controversial personality to come of power in Latin America in the last few years. Though he is nominally a member of a right-wing party, he has no organized political base but acquired national influence through wide exposure on television, where he poured his vitriol on ideological opponents, indeed, on anyone proposing any kind of government intervention in the economy. He is an unabashed animal lover, making sure to pay homage in his speeches to what he calls “mi hijitos de cuatro patas,” or my four-legged children. There is nothing wrong with that, but people look askance when he claims that he talks to his dead dog, Conan—named after the comics character “Conan, the Barbarian”—through a medium.

He has professional advisers, but the person who controls access to him and is said to be the power behind the throne is his younger sister, Karina Elizabeth Milei, who has been criticized for lacking any previous experience in government and having a background in business that consists mainly of selling cakes on Instagram. Still, she has elicited admiration for her micromanagement of her brother’s successful electoral campaign, prompting some to compare her to Evita Peron and Cristina Kirchner, the wife and successor of the late President Nestor Kirchner.

Mileinomics

Milei is personally quirky, and so, some say, is his economics. His intellectual hero is the radical libertarian economist Murray Rothbard. Reading an essay by Rothbard titled “Monopolies and Competition” was for Milei an experience akin to Paul’s conversion on the road of Damascus. “The article was 140 pages long,” Milei writes. “I went home to eat and began to read it. I could not stop reading, and after reading it for three hours, I said to myself, everything I had been teaching over the last 23, 24 years was wrong.” In addition to Rothbard, those in Milei’s pantheon of intellectual heroes are the paragons of neoliberal thinking, among them Friedrich Hayek, Leopold Van Mises, Milton Friedman, and Robert Lucas of the University of Chicago. (Milei has honored Lucas, Rothbard, and Friedman by naming his dogs, cloned with cells from the dead Conan, after them.)

It is not surprising that Milei condemns socialists, communists, Keynesians, and “neo-Keynesianos” like Paul Krugman. It is also not surprising that, like Friedrich Hayek, he considers the pursuit of social justice as a big mistake that is unjust and disruptive of the efficient working of the market and eventually leads to the “road to serfdom” by an all-powerful regulatory state.

What is unusual is that he includes a number of economists working in the neoclassical tradition in his sweeping condemnation of “bad influences.” Formerly an economics professor, he faults economic modelling promoted by the mathematization of economics for having led some analysts to the illusion that the market can lead to imperfect outcomes.

One fundamental tenet of neoclassical economics that elicits his ire is “Pareto Optimality,” which says that economic outcomes can be achieved that can make people better off without making anyone worse off. According to Milei, pursuit of Pareto Optimality by neoclassical economists has led them to the illusion that government action can improve market competition or make up for “market failure.”

Pareto Optimality, in his view, is the opening wedge that has led to the formulation and legitimation of other concepts such as imperfect competition, asymmetric information, public goods, and externalities—the solution or provision of which would require government intervention. The fundamental error of the economists who have generated these ideas is that they are so enamored with their models that “when their model does not reflect reality, they attribute the problem to the market instead of changing the premises of their model.”

Interfering with the operation of the market always has dangerous consequences, says Milei adamantly. Indeed, breaking up monopolies to bring about a state of perfect competition is erroneous, since monopolies, instead of being aberrations, are, in reality, positive “In fact, within a framework of free exchange, if a producer is able to capture the whole market, they have done so by satisfying the needs of consumers by providing them with a better quality product…The existence of monopolies in a context if free entry and exit is a source of progress, and the constant obsession of politicians to control them will only end up damaging the individuals they are trying to help.” In short, the market can’t make a mistake, and trying to rectify its supposed errors will only lead to a worse outcome for everyone.

Another classical economist that Milei has placed in the company of Marx, Pareto, and Keynes as an ideological baddie is Malthus, who held that the law of diminishing returns would create a situation where rapid population growth would not be supported by economic growth, leading eventually to general impoverishment. Milei claims that Malthus’s law has been disproven by the tremendous economic growth since the 19th century owing to technological advances made possible by the market, and Malthus’ only use these days is to provide intellectual support for the pro-choice movement, whose advocacy of abortion and family planning he despises.

The Opposition

Not suprisingly, Milei’s hostility has been reciprocated by the women’s movement, which fears that their successful effort to legalize abortion in 2020 will be reversed by the president.

Another sector of society that feels threatened by the new government is the human rights movement. Milei is not so much the object of hostility of human rights advocates as his vice president, Victoria Villaruel, who has defended the so-called dirty war waged by the military dictatorship of General Jorge Videla in the late seventies and early eighties that took over 30,000 lives. Villaruel, whose father and uncle were members of the military during the dictatorship, has opposed the trials of those being prosecuted for crimes against humanity and has threatened to begin investigation and prosecution of members of the Montoneros and ERP (Armed Forces of the People) accused of “terrorist crimes.” At the rallies of the two groups representing the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo that take place every Thursday afternoon at the Plaza de Mayo, participants are warned that Milei might allow Villaruel to pursue her vendetta against the memory of the disappeared.

No Counternarrative

The strongest opposition to Milei is the Peronist movement, which was the base of the governments of Nestor Kirchner, Cristina Kirchner, and Alberto Fernandez that have ruled Argentina for most of the last 24 years. It continues to have the support of some 30 per cent of the electorate. The problem is that neither Peronism nor the rest of the opposition has a counternarrative to Milei’s, admits Martin Guzman, former minister of the economy in the Peronist government of Alberto Fernandez and currently professor of economics at the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) at Columbia University.

Two obstacles lie in the way of the formulation of such a counternarrative. One is that while Peronism is a mass populist movement, its leaders have pursued conservative policies when in power, leading to the demoralization of the base. The second, and more significant obstacle, is that “the language and policies that animated Peronism’s working class base in the mid-20th century no longer connect with today’s young workers that are engaged in the gig economy perpetuated by savage capitalism,” according to Borroni, the radio journalist.

Milei and the Youth Vote

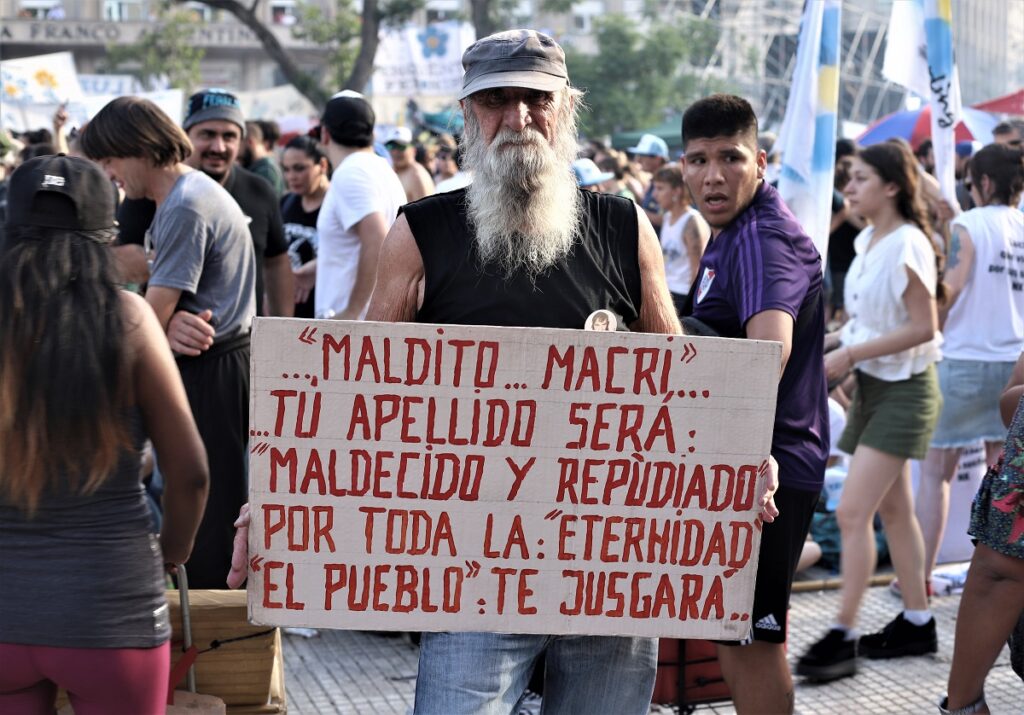

It bears noting that the strongest supporters of Milei are male voters in the 16 to 30 age group, 68 per cent of whom said they would vote for Milei in a poll taken before the November 2023 elections. Argentines who have grown up in the last thirty years have done so in a country that has been constantly in crisis, besieged by inflation, recession, and poverty, which now engulfs an astounding 55 per cent of the population, or 25 million people. To them both the center-left governments of Kirchner and Fernandez and the center-right regime of Mauricio Macri were abject failures in turning the economy around, making them vulnerable to the inflammatory rhetoric of Milei during the 2023 elections.

Argentina is a proud country, but for many young Argentines, there is little these days to be proud of except perhaps Lionel Messi and the national soccer team (and even they have been tainted by a recent incident where some players were captured on video singing a racially offensive song regarding the African origins of many of those in the French national team that fought Argentina in the World Cup finals in 2022).

Destined to Fail?

Milei has promised to restore Argentina to its 19th century status as one of the richest countries in the world. But it is difficult to see how Milei will get Argentines out of their economic conundrum and restore their morale as a country. His vision is that of an Argentina of the future purged by the fire and sword of radical austerity and shorn of the “political caste and army of parasites whose only objective is to perpetuate itself in power by sucking the blood of the private sector.” The measures he is taking , however, are likely to follow the well-trodden path of similar programs in the Global South and in Greece and Eastern Europe after the 2008 financial crisis, that is, continuing economic contraction or prolonged stagnation. What is remarkable is that despite the record of unremitting failures of neoliberal programs to deliver sustained growth over the last quarter of a century, there are still intellectual and political leaders like Milei who continue to embrace them. Milei is, in fact, vulnerable to the same error he accuses neoclassical antagonists of committing: that when theory and reality diverge, it is reality that is the problem.

At some point a program of vigorous government action to trigger growth, redistribute income, and reduce poverty may perhaps become attractive again and voters may turn on Milei’s counterrevolutionary economic project. “I have no doubt that Peronism will again come to power,” asserts Borroni. “Whether it will come to power as a a genuine popular movement or in the guise of a popular movement led by the right is the question.” But will such a new and improved version of Peronism be able to finally lick Argentina’s poisonous galloping inflation while promoting growth and reducing inequality–that is the bigger question.

“Other countries have been able to control inflation. Why can’t we?,” one Argentine I interviewed asked in frustration. That same question is on everyone’s lips, but for the moment, people seem to have suspended their skepticism and given the mercurial Milei some slack.

This article is based on a recent trip the author made to Argentina that was supported by a travel grant from International Development Associates (IDEAs). It first appeared on Meer and it is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

Walden Bello is Co-chair of the Bangkok-based Focus on the Global South affiliated with the Chulalongkorn University Social Research Institute and honorary research fellow with the Sociology Department of the State University of New York at Binghamton.

Cite as: Bello, Walden 2024. “The Mess in Argentina” Focaalblog 2 October. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/10/02/walden-bello-the-mess-in-argentina/