I would never have expected Ruth to join the revolution. But then so much of what’s happened in Myanmar this past year has been somehow unexpected, from the coup itself, in the early hours of 1 February, to the scale of the popular reaction. Friends who expressed little interest in politics or protest during my fieldwork, only a few years ago, have been in the streets. Striking has been the role of young women—women like Ruth, a Christian born in the Chin Hills, who works at a church in Yangon where I did much of my research.

As the uprising grew through February, Ruth’s posts filled my Facebook feed: selfies in Covid-19 masks amid swelling crowds around the Sule Pagoda; memes mocking the generals behind the coup; photographs of victims shot by security forces. One thing not surprising has been the brutality of the crackdown. As it intensified in late February and early March, Ruth’s posts showed her wearing not just a face mask, but also a helmet and goggles.

As Pentecostals, believers like Ruth have also been praying. One video streamed via Facebook Live had about twenty members of her church engaged in a session of collective prayer, entreating God to protect Myanmar. Such prayers were commonplace during my fieldwork. But this one resonated with the revolution then building momentum in the streets: put to the rhythm of a familiar call-and-response chant made famous in the 1988 uprising, the prayer replaced the usual rejoinder “do ayei! do ayei!” (“Our cause! Our cause!”) with “Amen! Amen!”

What draws these Christians so fully into the revolution through protest and prayer? There’s been much said about how a decade’s experience of a more open public sphere makes return to military rule impossible to countenance. Many have also remarked on how this moment has transcended lines of difference that have long animated Myanmar’s politics, with Chin Christians and even Rohingya Muslims manning barricades alongside majority Burman Buddhists.

But maybe part of an answer also lies in the imagination.

I say this, in part, because of another question I’ve had, watching Myanmar’s Spring Revolution unfolding from afar over social media: What would David Graeber make of this?

Graeber never wrote about Myanmar, but he was, of course, deeply interested, intellectually and practically, in revolution. And for him, the question of revolution was tied to the question of imagination. In one essay (2007), he distinguished a “transcendent” form of imagination, the terrain of fiction and make-believe, of “imaginary creatures, imaginary places … imaginary friends”, from an “immanent” form, one not “static and free-floating, but entirely caught up in projects of action that aim to have real effects on the material world … ”. It was the latter, for Graeber, that had revolutionary potential.

While Graeber never wrote about Myanmar, had he not died in September 2020, that might not have remained true for long.

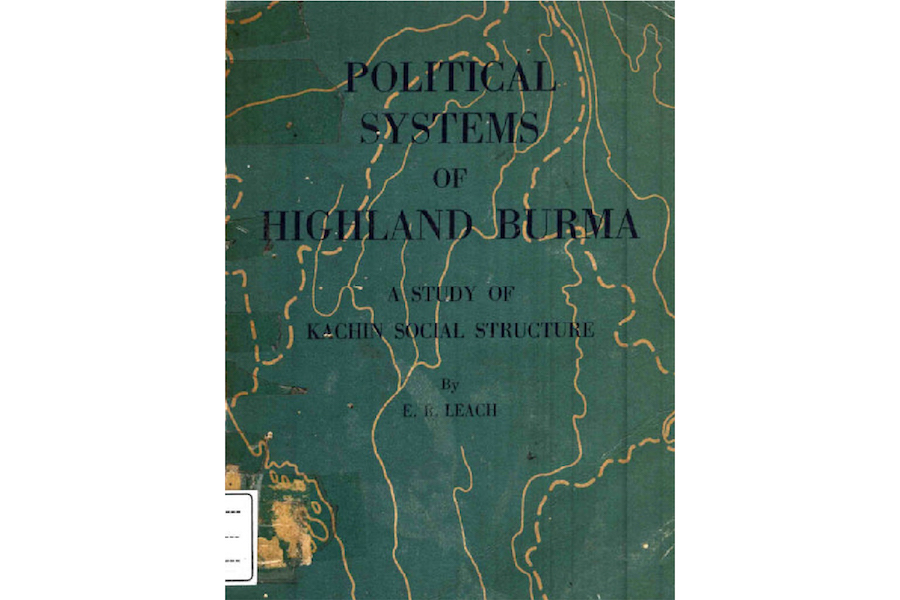

Some years ago, he agreed to write the foreword to a new edition of Edmund Leach’s Political Systems of Highland Burma. The foreword was never finished, so we can’t know what Graeber would have written. We can’t know how he would have engaged with Raymond Firth’s original, laudatory foreword. We can’t know how he would have dealt with Leach’s later reappraisal, when he acknowledged that he had somewhat essentialised gumsa and gumlao, the Kachin categories famously at the heart of his analysis. We can’t know how he would have situated the book in relation to debates in anthropology in the decades since, or how he would have dealt with critiques that have been directed towards it, including from Kachin scholars (e.g., Maran 2007), and especially amid growing calls to meaningfully decolonise the study of Myanmar.

What we do know is that Graeber was a fan. “Edmund Leach,” he once wrote, “may have been the man who most inspired me to take up an anthropological career.” Leach was, for Graeber, “a model of intellectual freedom”. References to Leach appear across Graeber’s body of work, including citations of the younger Leach and the older Leach following his so-called “conversion” to structuralism—a break which, as Chris Fuller and Jonathan Parry note, has probably been overdrawn. “Not only are there striking continuities in the sort of questions Leach asked of data,” they write, “and the sort of answers he offered, but more importantly he kept faith throughout his career with one broad vision of the anthropological enterprise” (1989: 11).

If the same might be said of Graeber, it’s not the only way in which the two men were similar. Both thought across relatively long stretches of time: 140 years in the case of Leach’s study of the oscillations in Kachin political systems; millennia in the case of Graeber’s work on debt and his recent collaboration with David Wengrow. Both were also prolific and lucid writers, eager to engage audiences beyond anthropology—including, incidentally, via the BBC, which broadcast Leach’s Reith Lectures in 1967 and Graeber’s 12-part series on debt in 2016.

What James Laidlaw and Stephen Hugh-Jones (2000:3) write about Leach could just as easily be said of Graeber, that “the lessons of anthropological inquiry were relevant to the everyday moral and political questions that were being debated all around him …”. Both were interested in the micro and macro forces that impacted the production of knowledge in anthropology, and both reflected on how their own biographies and albeit very different insider/outsider positions in the discipline shaped the work they produced (Leach 1984; Graeber 2014).

There are, however, few references to Political Systems in Graeber’s corpus, which raises another question: What would he have written in this foreword?

It’s impossible to attempt a definite answer. Graeber was far too creative for that. But it’s probably not going too far out on a limb to suggest that imagination might have been a central theme. For what are the political categories of gumsa and gumlao analysed by Leach if not products of the “immanent” mode of imagination that interested Graeber? One reference that does appear at several points in Graeber’s writing is to a point Leach made in his short 1982 treatise simply titled Social Anthropology. There, Leach suggests that the distinction between humans and non-humans is not that the former have a soul, but that they are able to conceive—or imagine—that they have one, and thus, that it is imagination, not reason, that sets humans apart. On this point, Graeber also (e.g., 2001: 58) cites Marx’s observation that, unlike a spider weaving its web or a bee building its nest, “the [human] architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality.”

If imagination is, for Leach and Graeber, a general feature of the human condition, it’s also one thrown into relief at certain moments, like moments of revolution. “When one tries to bring an imagined society into being,” Graeber wrote, “one is engaging in revolution” (2001: 88). It’s maybe not too much of a stretch, then, to also imagine that, if he had been writing the foreword to Political Systems this past year, Graeber would be attending to the revolution underway in the valleys and the highlands that feature in Leach’s book: a revolution whose participants, like Ruth, imagine not just a political system in Myanmar with the military no longer in charge, but a society transformed in myriad other ways.

Around 2011, as Myanmar started to emerge from five decades of military rule, Ruth’s church and other Pentecostals intensified their evangelism efforts, seeking to win converts in a country where about 90 percent of the population are Buddhist. Taking advantage of the political opening, and with an eye to the spiritual rupture it was thought to herald, these Christians began to preach more energetically than they had in years.

But even before the coup, there was evidence that the rupture might not be forthcoming: a sense that liberalisation was benefitting only well-connected cronies; new forms of censorship impinging on what was supposed to be a newly open public sphere; an ascendent Buddhist nationalism rendering increasingly precarious the position of minorities, and playing out horrifically in the treatment of the Rohingya. There were also few signs that Buddhists were suddenly interested in Jesus. This did little to dent my friends’ commitment to evangelism, however. “God works in his own time,” was the frequent refrain.

How, in this understanding, to make sense of the coup?

The immediate days after the military seized control, detaining elected leaders including Aung San Suu Kyi, were strangely quiet. Healthcare workers and teachers were among the first to go on strike. Garment workers followed soon after. As the civil disobedience movement took shape, more people took to the streets. By the middle of February, tens of thousands of protesters were assembling each day in Hledan, a busy commercial neighbourhood near Yangon University.

Ruth was among them. We’d been in touch since the hours following the coup. She sent photos and videos of the swelling crowds. In one image her white sneakered foot stamps on a poster of the face of Min Aung Hlaing, the general behind the coup, taped to the pavement for protesters to walk over. In another she holds up a placard with the words #justiceformyanmar alongside an image of Aung San Suu Kyi, the imprisoned NLD leader. “Young people will not be turning back,” she wrote in one message.

The spokesperson for the parallel government established by the parliamentarians deposed by the coup has been a prominent Chin Christian doctor, Dr Sasa. At certain points protest signs featuring his face seemed to eclipse those featuring Aung San Suu Kyi’s. In late February Ruth posted an old photo of her with Dr Sasa, with the caption, “May the Lord bless you and use you for our nation and His kingdom.” Dr Sasa’s role has been particularly important to my Chin friends, accustomed, like other ethnic minorities, to being treated like second class citizens, if citizens at all, by a state whose leadership has been dominated by Burman Buddhists.

The literature on ethnicity in Burma has often been in dialogue with Leach, for better and for worse. His arguments in Political Systems are so well known to anthropologists that they barely need repeating. His analysis of oscillations between political categories—the hierarchical gumsa and the egalitarian gumlao—is deployed to attack the equilibrium assumptions of his structural-functionalist colleagues, and their allied tendency to treat ethnic groups as bounded units. Social systems, Leach argues, do not correspond to reality. They are models used, by the anthropologist and those they study, to “impose upon the facts a figment of thought”.

Such models find their clearest expression, for Leach, in myth and ritual, which present the social order in its ideal form, conjuring it by acting “as if” it already existed. Such a model, importantly, does not float freely from the messy world of social facts; it “can never have an autonomy of its own” (1964: 14).

Critics of Leach have homed in on his nonchalant confession, toward the end of the book, that he is “frequently bored by the facts” (1964: 227). This attitude, they charge, means that his analysis floats more than a little too freely. “[O]ne might with justification,” write Mandy Sadan and Francois Robbine, “accuse Leach of reducing the Kachin sphere to a kind of intellectual laboratory without any expression in reality because of the way in which he moulded his case study to a theory, rather than the other way round” (2007: 10-11).

I’m sure Graeber would have dealt with these criticisms in his foreword, but less certain what he would have said about them, or how his own view of the relationship between facts and theory would have shaped his assessment. My main hunch, though, is that Graeber would have devoted much of his foreword to what Leach tells us about the “as if”—the otherwise glimpsed in ritual and myth but still tethered to social action. Such an otherwise, the space of the immanent imagination, drew Graeber’s attention throughout his anthropology, even when he wasn’t using the term.

Consider his foreword to another book, The Chimera Principle by Carlo Severi, which deals with the relationship between ritual objects, memory, and the imagination. Graeber praises the book for showing that “imagination is a social phenomenon, dialogic even, but crucially one that typically works itself out through the mediation of objects that are … to some degree unfinished, teasingly schematic in such a way as to, almost perforce, mobilize the imaginative powers of the recipient to fill in the blanks” (p. xv). When communicated in the subjunctive mood of myth or ritual, such an imagination can, to use a term of which Graeber was fond, prefigure realities to come.

The crackdown in Myanmar grew more brutal through March. Protesters like Ruth continued to be in the streets. By late February, we’d shifted our conversation from Facebook Messenger to Signal because of the safer encryption that app offered. Still, Ruth continued to post on Facebook, using a private VPN to access the site in the face of the junta’s effort to block it, and, periodically, the internet altogether. Her content grew more graphic. In early March she posted a widely circulated video of three paramedics being beaten by security forces. Videos of shootings followed daily. Posts were often accompanied by the slogan, “The revolution must succeed”.

It’s now been one year since the coup, and Myanmar’s revolution has continued to evolve. Just as the country ought to be considered world historical, so those involved in the uprising continue to make history, through their ongoing resistance amid a military assault that has been especially vicious in Chin State and other ethnic areas.

What would Graeber have made of this unfolding revolution?

Unfolding is the operative term. “Every real society is a process in time,” Leach famously writes in the introduction to Political Systems. And, as Tambiah (2002: 443) suggests, there is much in Leach that resonates with—prefigures, perhaps—Fabian’s (1983) critique of anthropology’s routine “denial of coevalness.” There’s an irony, then, that many of the strongest critiques of the book focus on Leach’s elision of the historical circumstances in which his study occurred, something about which Graeber would have no doubt remarked, especially if his treatment of another major figure in British anthropology, Evans-Pritchard, is anything to go by.

There are certainly important differences between Graeber and Leach, political and otherwise, but one other thing they had in common is that they were not just prolific writers, but prolific readers too. There’s been much said about the place of the imagination in the writing of anthropology, but less, perhaps, about imagination’s role in its reading. If all ethnography is “fiction”, as Leach claimed in one of his final lectures, and even if it isn’t, what imaginative faculties are engaged in reading it?

What modes of speculative reading do we pursue, though gaps, from afar, of Facebook posts, of texts that don’t, really, exist? In his foreword to Severi’s book, Graeber pushes against the “utopian ideal” of a text produced by a “single, unique” genius. Instead, he argues, “everything turns on a tacit complicity, whereby the author leaves the work, in effect, half-finished so as to ‘capture the imagination’ of the interpreter” (2015: xx-xxi).

How do we read with an imagination that is a “social phenomenon, dialogic even,” one that works through the mediation of things unfinished and incomplete?

Unfinished, unfolding, incomplete—like Myanmar’s revolution. Ruth is also working in the presence of something that doesn’t, really, exist, and didn’t even in the years of so-called transition: a democratic Myanmar that is both politically—and, for her, spiritually—saved. But in continuing to defy the military, just as she continued to evangelise in the face of indifference, she and others act “as if” they live in a world not just where “the revolution must succeed,” but in which it already has, and in imagining that world, they work to bring it into being.

Michael Edwards is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Centre of South Asian Studies at the University of Cambridge. He’s writing a book about the encounter between Pentecostalism and Buddhism in the context of Myanmar’s so-called transition.

This text was presented at David Graeber LSE Tribute Seminar on ‘Myth and Imagination’. A longer version of this essay will appear in a volume organised around David Graeber’s anthropology, edited by Holly High and Joshua Reno.

References

Fuller, Chris and Jonathan Parry. 1989. “Petulant Inconsistency? The Intellectual Achievement of Edmund Leach”. Anthropology Today 5/3: 11-14.

Graeber, David. 2001. Toward and Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York: Palgrave.

Graeber, David. 2007. Revolutions in Reverse: Essays on Politics, Violence, Art, and Imagination. London: Minor Compositions.

Graeber, David. 2014. “Anthropology and the rise of the professional-managerial class”. Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4/3: 73–88.

Graeber, David. 2015. “Concerning Mental Pivots and Civilizations of Memory.” Preface to The Chimera Principle: An Anthropology of Memory and Imagination. Chicago: HAU Books.

Laidlaw, James and Stephen Hugh-Jones. 2000. The Essential Edmund Leach, Volume 1. Anthropology and Society. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Maran, La Raw. 2007. “On the continuing relevance of E. R. Leach’s political systems of Highland Burma to Kachin studies”. In M. Sadan and F. Robbine (eds.) Social Dynamics in the Highlands of South East Asia: Reconsidering ‘Political Systems of Highland Burma’ by E. R. Leach. Leiden: Brill

Leach, Edmund. 1964 [1954]. Political Systems of Highland Burma. Boston: Beacon Press.

Leach, Edmund.1984. “Glimpses of the unmentionable in the history of British social anthropology”. Annual Review of Anthropology 13: 1-23.

Sadan, Mandy and Francois Robbine (eds.) 2007. Social Dynamics in the Highlands of Southeast Asia: Reconsidering ‘Political Systems of Highland Burma’ by E. R. Leach. Leiden: Brill.

Tambiah, Stanley J. 2002. Edmund Leach: An Anthropological Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cite as: Edwards, Michael. 2022. “Graeber, Leach, and the Revolution in Myanmar.” FocaalBlog, 27 January. https://www.focaalblog.com/2022/01/27/michael-edwards-graeber-leach-and-the-revolution-in-myanmar/