Coronavirus has provoked some of us to think about our worlds in new ways and to consider different horizons of change. Yet in many pandemic-related discourses and policies, I have been frustrated to see hegemonic ideals about care, kinship, and residence distract attention from empirical realities and adequate solutions. Examples range from the ubiquitous representation of care as embodied by women health workers and mothers to the shocking silence about disproportionate burdens of coronavirus illness and death born by men, and the wildly incorrect assumption that most humans live in and are cared for by nuclear family households.

Covid masculinities

Much attention has been drawn to vulnerabilities of women nurses, health aids, and caretakers. More gender awareness is needed for millions of men performing essential jobs as sanitation workers, truck and bus drivers, agricultural workers, miners, fishers, and loggers. These occupations are absolutely vital for public health, yet were already among the most dangerous and deadly before adding exposure to coronavirus. Around the world, they are performed overwhelmingly by men, in patterns of workplace violence so highly gendered that, in countries like USA, men suffer 92% of occupational deaths. The workplace, then, is a realm that calls urgently for improved care.

Data from countries around the world show that coronavirus infections tend to be much more severe among men than women, with death tolls as high as two times greater for men (Bhopal and Bhopal 2020). In the US, the death rate from coronavirus for men is 1.6 times that of women. This intersects with disproportionate burden of coronavirus infections and underlying conditions among racial and ethnic minorities, and among those who are less wealthy and less educated. In many contexts, then, it is poorer less-white men who are most vulnerable to suffer critical illness and death from coronavirus (Rushovich et. al 2021). Care for these groups needs to be much more visible in news and policy responses.

While analyses of structural inequalities in occupation, residence, and healthcare rarely address masculinities, some airtime has been dedicated to men’s behavior. Studies in various contexts found men to be much more likely than women to go without masks and to break quarantine. How can criticism of the behavior of individual men shift to societal commitments to supporting self-care among all humans, including variously positioned men?

Is it useful to blame men for getting sick? Feminists have struggled to motivate compassion for women whose conditions constrain the development of skills and confidence needed to establish dignified lives for themselves. Transitions to care-full worlds will also require compassion for boys and men whose gender expectations push them to demonstrate their manliness by performing dangerous labor in hazardous conditions, by exercising and enduring violence, and by taking risks with their health and their lives. Perhaps the devastating gendered impacts of the virus can spark mobilization against gender-linked violence that harms men and women in different ways.

While some people find safety and comfort at home, others face conflict and crowding, or lack homes altogether. Reports from diverse countries indicate that domestic violence has intensified during lock-downs, impacting women disproportionately. People who don’t even live in homes face different kinds of vulnerabilities. In most countries, women outnumber men among residents in long-term care centers, while men make up majorities as high as 90% in prisons, jails, migrant labor camps, homeless shelters, immigrant detention centers, and military barracks, all of which became hotspots for the virus. In these residential patterns too, the forms of violence and discrimination borne by men intersect with ethno-racial and class inequalities. Demands of care for those not living in households call for moral and institutional shifts away from private family responsibility toward community and commons.

Normative households

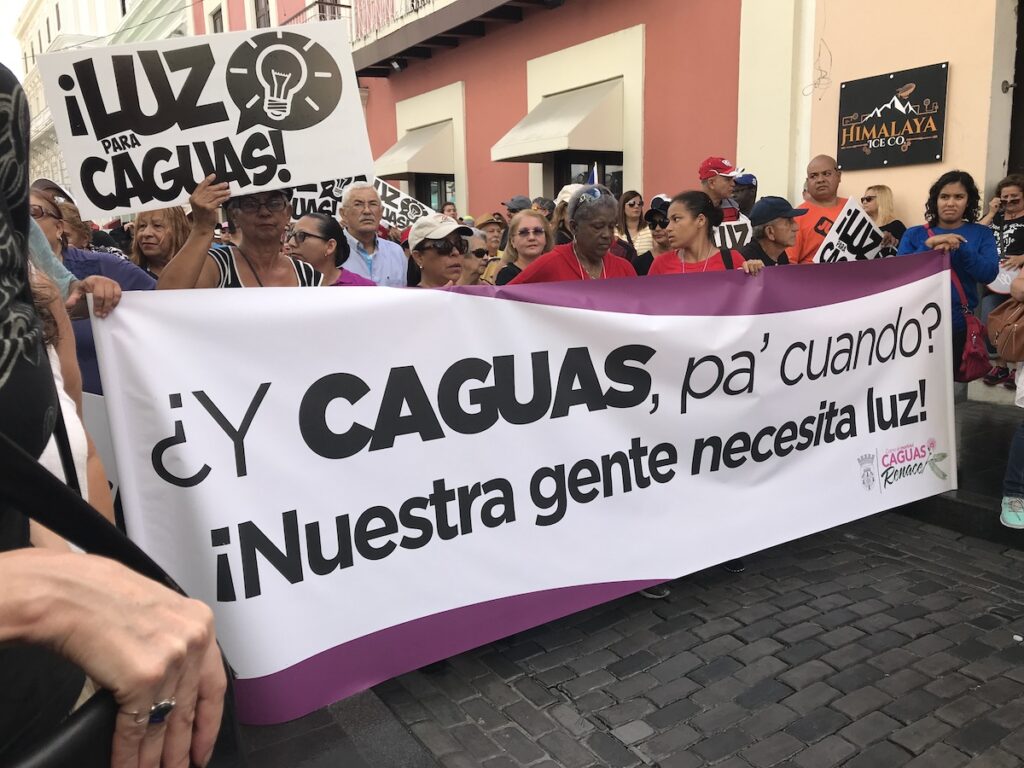

Kinship and sexuality are also fundamental in the organization of care. Many public health messages, exemplified by those pictured below, reinforce the widespread—and incorrect—assumption that contemporary populations live mostly in heteronormative nuclear households. In the US, however, only 20% of households consists of nuclear families, as measured by the US Census Bureau. Can we do better at supporting the other 80% to respond to this pandemic and conditions of life beyond?

The false portrayal of residential life as reflecting a normative kinship model limits support for the actual residential and kin arrangements through which care and provisioning are organized in today’s societies. Inaccurate assumptions that all people live like the Flintstones, the Simpsons, or the Jetsons seriously limit public health efforts by obscuring empirical realities, which are plural. Those public messages also operate to demean and delegitimize other ways of living, and to stifle creative responses to coronavirus and other challenges.

Across wealthy countries, the most common household category is a single person living alone (27% US and Canadian households, 40% of Swedish households). This New Yorkers Stay Home poster taps into possibilities of nourishing companionship in uni-person households through literature and interspecies relations (human & plant). Another creative response to needs for care and conviviality is found in queer dance parties organized online with scopes ranging from local communities to celebrity-filled global gatherings. This is not a trivial example; opportunities to dance, laugh, move together not only provide care and acknowledgement needed in quarantine (and other isolating conditions), they can also build values and pleasures outside the realm of economic competition, consumption, and profit. Alliances with LGBTQ and related social movements help to honor the diverse household and kin arrangements that people are already living, and to support innovations provoked by the pandemic, as well as those motivated by desires for positive transformation.

Where did this ill-fitting model come from?

Generations of anthropologists and archaeologists have documented a rich variety of arrangements for care, protection, provisioning, and regeneration of human communities. These are often lumped together under the term “extended family,” reinforcing the false assumption that all kinship is based on the nuclear family, from which other relations may “extend.”

Today, much public discourse, together with a surprising amount of academic work, ignores the diverse realities of kinship across cultures and through history, and instead features an ideological model of (re)production that was established and disseminated with the rise of colonial capitalism, through the following historical processes:

- conceptual and institutional divorce of market-oriented activities identified as “productive labor” from other activities identified as “reproductive care“

- designation of the first as “masculine” and the second as “feminine” allocation of disproportionate monetary value, resources, and power to masculine-associated production

- 20th century push toward nuclear family households as economic and residential unit

- media, political, and educational messages convey expectations that human organization be based in heteronormative nuclear family households where men are excluded from care work

What drives ongoing pushes to keep imposing this model on populations that it so poorly represents? Why continue allocating responsibility of care to putative nuclear families in strategies that overburden some and fall short of needed care for many?

One key motive is the role this model has played as an instrument of industrial capitalist growth, adapted to engineer and to justify forms of appropriation that support profit and accumulation. The model has also been instrumental to the militarization of domestic and international conflicts related to this push. For me, then, challenging normative assumptions about this gender-kinship model is a vital move to curb and to heal eco-social damages provoked by the drive for growth.

What policies, practices, messages can support and motivate people of all identities to organize care with healthier arrangements of care?

A silver lining can be found in the potential of historical crises (like COVID-19 and climate break-down) to destabilize established orders, opening possibilities for new alliances toward healthier and more equitable worlds.

While respect for planetary boundaries demands degrowth of the total quantities of resources and energy transformed each day by the global economy, some features need to be nurtured and developed, namely infrastructures and institutions of care that enhance the well-being of more people in more places. Care-full paths forward are being explored by Degrowth and Feminism(s) Alliance (FaDA), in contexts including the coronavirus pandemic (Paulson 2020).

Amid the pandemic, we have been happily surprised to see governments experimenting with policies proposed in our book The Case for Degrowth (Kallis et al. 2020): companies and governments have reduced working hours, implemented work-sharing, and subsidized workers during quarantine and business closings. Enhanced public services have supported household and community economies, and mechanisms such as the US Defense Production Act have been mobilized to secure vital supplies and services.

Can we think about these moves as anticipatory strategies that may secure ongoing care for populations, and slow down the rush toward future disasters? For example, can provisional cash payments to sustain residents through the crisis lead the way to basic care incomes? Can defense budgets shift emphasis from updating military armaments toward protecting and regenerating human resources?

Policies like these may work in very different ways, depending on the degree to which they are institutionalized to stimulate economic growth or to promote equitable wellbeing; to prolong productivism or to support reproduction; to provide charity for vulnerable people or to replace hierarchical and exploitative social systems that produce those vulnerabilities.

Beware that these crises also nourish divisive and reactionary alliances. Amid the ongoing pandemic, powerful actors continue pushing to reconstitute the status quo, and to shift costs to others. There is danger that abilities to ally for change will be undermined by politics of fear, xenophobia, and blame; intensified surveillance and control; and isolation that constrains political organizing and all kinds of common efforts. Campaigns to discredit vaccinations and masks synergize with attacks against climate action, gender equity, and racial justice. All are rallied in the name of political economic stability and defense of geopolitical interests. On personal levels, this allied resistance to change is fueled by understandable fear of losing identities and relations that have been construed and experienced as natural, meaningful, and morally correct (even as I understand them as historically adapted to support growth). In the face of polarizing narratives and blame, what strategies can support shifts away from divisive competition toward mutual collaboration?

Conclusion

I would like to see economies slow down by design, not disaster, in ways that support societies to become more caring and equitable. However, it looks like transitions may be unplanned and messy, like those we are living through now. Finding ourselves amid global pandemic and climate change, we must seize opportunities to build healthier priorities, policies, and sociocultural systems. Such transitions depend on alliances among differently positioned actors. And they must involve attention to gender and kinship systems that honor diverse contributions, and that assure care and minimize vulnerabilities for all.

Susan Paulson is Professor at the University of Florida’s Center for Latin American Studies. She studied and taught about human-environment relations during 15 years in Latin America, and taught sustainability studies during 5 years in Europe. Paulson contributes to theory and practice in political ecology; degrowth; and gender, masculinities and environment.

References

Bhopa, Sunsil and Raj Bhopal. 2020. ‘Sex differential in COVID-19 mortality varies markedly by age.’ Lancet 396 (10250): 532-533.

Kallis, Giorgos, Susan Paulson, Giacomo D’Alisa, Federico Demaria 2020. The Case for Degrowth. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Paulson, Susan 202. ‘Degrowth and feminisms ally to forge care-full paths beyond pandemic.’ Interface: A journal for and about social movements. Volume 12 (1): 232 – 246. https://www.interfacejournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Interface-12-1-Paulson.pdf

Rushovich, Tamara, Marion Boulicault, Jarvis T. Chen, Ann Caroline Danielsen, Amelia Tarrant, Sarah S. Richardson, and Heather Shattuck-Heidorn 2021. ‘Sex Disparities in COVID-19 Mortality Vary Across US Racial Groups.’ Journal of General Internal Medicine 36: 1696-1701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06699-4.

Cite as: Paulson, Susan. 2022. “Gender-aware care in pandemic and postgrowth worlds.“ FocaalBlog, 26 April. https://www.focaalblog.com/2022/04/26/susan-paulson-gender-aware-care-in-pandemic-and-postgrowth-worlds/