A few months before the Covid-19 lockdowns were implemented globally I travelled to the border between Venezuela and Brazil for a stint of ethnographic fieldwork about the complex humanitarian crisis. By that time more than five million Venezuelans had left the country, and hyperinflation was mindboggling. Inflation had reached more than 9500%, making living and working with the national currency impossible. The steep currency breakdown not only intensified the exodus of millions of Venezuelans, but also a gold rush in the Venezuelan South. At the border with Brazil, many Venezuelans were going back and forth with fuel, food, gold, and foreignbanknotes.

When Covid-19 lockdowns were temporarily lifted in October 2021, I arrived in Caracas for another short field trip. The new bolívar digital had started circulating only five days previously—the digital was the third new analogue currency since 2008 to get rid ofyet anothersix digits. I have only ever once seen a bolívar digital, including during an additional six months stay in 2023. Venezuelans I spoke with over the years did not really care about their national currency anymore. The bolívar digital appeared to concentrate only in subsidized exchanges, tax payments, and public transport. Instead, US dollars, Brazilian reais, Colombian pesos, crypto currencies, and gold are now largely being used for ordinary trade and subsistence. These de facto currency substitutions during the period of Covid-19 lockdowns gave a significant boost to the crashed economy, at least temporarily. With so many different currencies in circulation, I became interested in the way the disappearance of the bolívar as accepted currency also seemed to involve a form of moral loss.

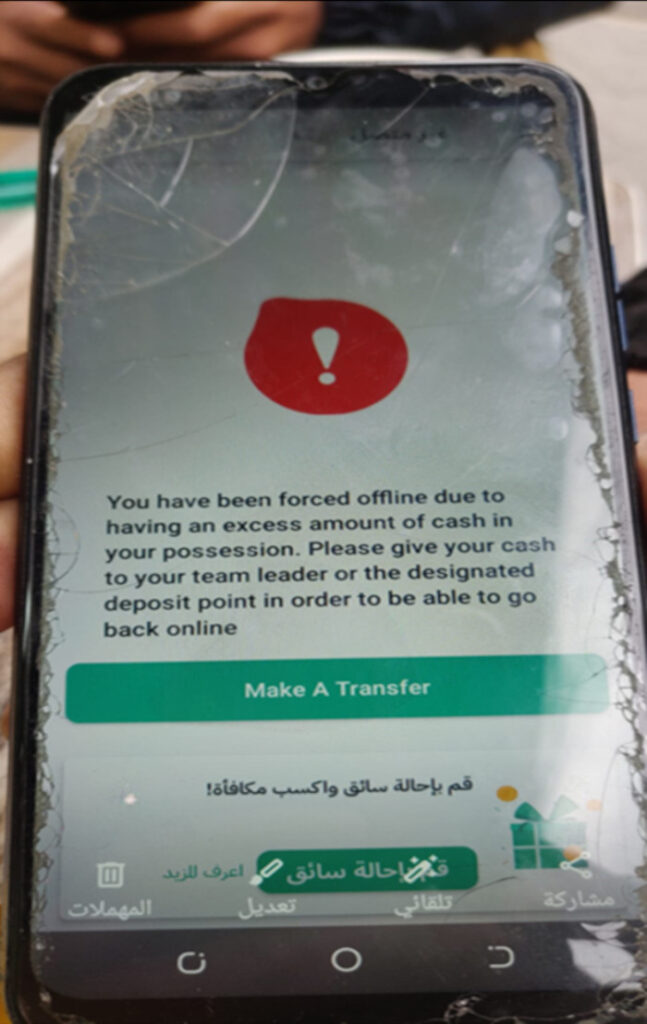

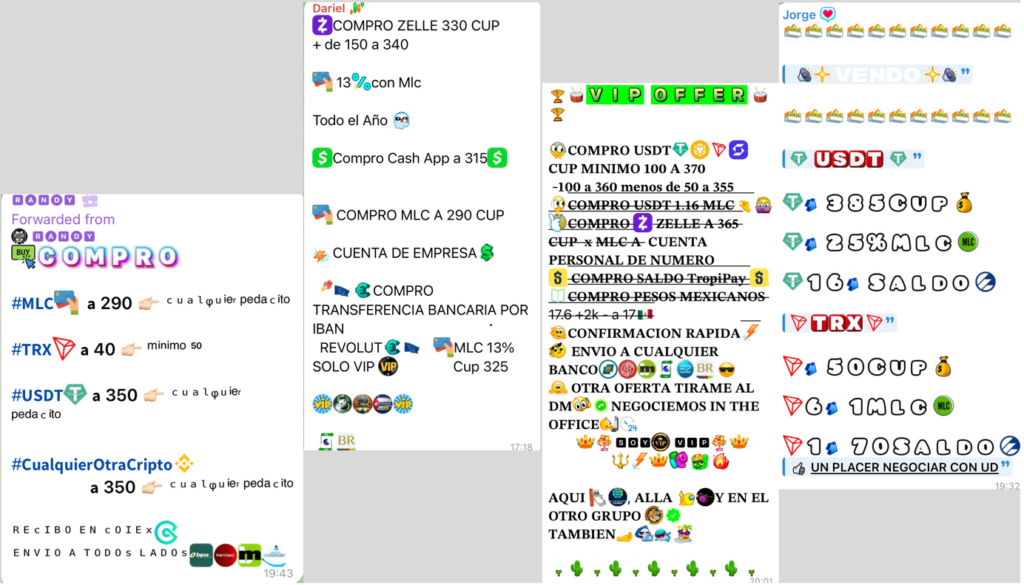

Since 2020 Venezuelans have found multiple ways to get hold of digital dollars through the steep increase of using new electronic payment systems, like Zelle which is – now I paraphrase their website: ‘an easy and quick way to send small amounts of money directly to almost any U.S. bank accounts with just an email or US mobile phone number.’ Without such linkages to the US finance system, Venezuelans were largely excluded from receiving cambio (spare change) at any shop in Venezuela. I have witnessed innumerable conflicts at shops and gas stations around lack of cambio, becauseone is simply forced to top up purchases or receive a bunch of unwanted candy.

Using multiple currencies is not only helpful for payments. Being new to the field of finance and economics, I quickly learnt that inflation is big business. Some of my friends had a remarkable knowledge of which banknotes and cryptocurrencies to trade and when to trade them. I must admit that I found these new businesses a bit of a sour promise from which very few really benefited, and far outweighed the daily frustrations of chronic lack of cambio and the utter confusion of constantly using different banknotes.

These everyday experiences of hyperinflation seem to be embedded in entrenched cultural and historical meanings attached to money and natural resources. What promises and everyday frustrations do people encounter in abandoning their national currency? What can the rapid shift to a multi-currency economy tell us about local ideas of autonomy and self-government? How does present monetary loss relate to previous economic bonanzas in people’s experiences of money? Ultimately, I am interested in what the moral, political, and economic critiques and assessments of “ordinary” Venezuelans around the complex humanitarian crisis can tell us about the moral loss and extinction of certain life forms.

A brief history of hyperinflation and de facto currency substitution in Venezuela

Between 2013 and 2019, Venezuela lost more than 60 per cent of its GDP (Bull and Rosales 2020, 2). The minimum wage plummeted far below the United Nations standard of extreme poverty ($1.25 a day) and, in 2019, nearly 90% of the population was poor or extremely poor. Although any statistic about Venezuela is unreliable, hyperinflation in 2018 was estimated to reach the incredible figure of ten million percent. That is 8-digit inflation.

Venezuela’s economic climate and its national currency is intimately tied to critical natural resources, and oil in particular. As a petro-state since the early twentieth century, Venezuelans are used to steep boom and bust cycles, but the recent runaway inflation has been on a scale unseen even by Venezuelans. It is even said to be the most significant economic collapse-outside of war-in over four decades (Corrales 2019). Yet, the current crisis shows clear parallels with economic crises in the 1990s, when Venezuela also faced the highest inflation rate of the continent (“only” 70 percent) (Coronil 1997).

Since 1983, soaring inflation has heavily affected Venezuela’s economy and its national currency the bolívar. In the early twenty-first century, thanks to another oil boom, inflation became temporarily manageable but was still in the double digits. Governments from this period implemented various new currencies. In 2008, the bolívar fuerte (the strong bolívar) saw the light of day, getting rid of three zeros. The government pegged its value to the US dollars creating immediately a parallel exchange rate market. In 2012 another abnormal inflation started which lasted for more than a decade. This prompted the introduction of another currency in 2018, the bolívar soberano (the sovereign bolívar), getting rid of another five zeros. And in 2021, the government introduced the already mentioned bolívar digital getting rid of six zeros. Formally, both the soberano and the digital were circulating until August 2024 when the government issued a decree removing from circulation bolívar soberano banknotes with denominations of 10,000, 20,000, 50,000, and 200,000. But in practice most analogue transaction happen in foreign currencies or gold.

Conjuring the morality of money

After more than forty years of experiencing inflation, it is fair to say that Venezuelans are used to navigating monetary volatility. The bolívar went from the strongest currency in the region in the 1970s to the world’s least-valued circulating currency in 2018. I do think there appears to lie a difference in degree when it comes to how people experience and assess inflation on their own terms. Double digit inflation is clearly something other than eight-digit inflation for Venezuelans. Ongoing loss of value for the bolívar had caused a form of ‘socially constructed perplexity’ as Matt Wilde (2023, 162) poignantly argues in his recent ethnography on oil politics and the Bolivarian Revolution. Given the chronic history of inflation, worthless money was perhaps still imaginable for some of my Venezuelan friends, but that their oil nation was facing such extreme levels of poverty and hunger baffled almost everyone.

How people position themselves to their currency and relate to money in general is culturally situated as Martin Holbraad (2017, 92) argues for the Cuban case: monetary relationality is also subject to moral change. Like the oil boom of 1973, when norms about money changed due to the immense flow of petrodollars into Venezuela (Coronil 1997, 11), the recent experience of hyperinflation is resignifying how Venezuelans value and use their currency, as part of a larger process of changing social and affective relations with the state and society. It is here where I want to conjure the moral value of oil money. The recent turn in moral anthropology is particularly supportive for exploring questions of moral loss and ethical being in times of runaway hyperinflation because it provides analytical space to explore, as James Laidlaw argued a decade ago (2014, 15), “the role of ethical thought and practice in understanding phenomena that span the range of anthropological topics and ethnographic contexts.”

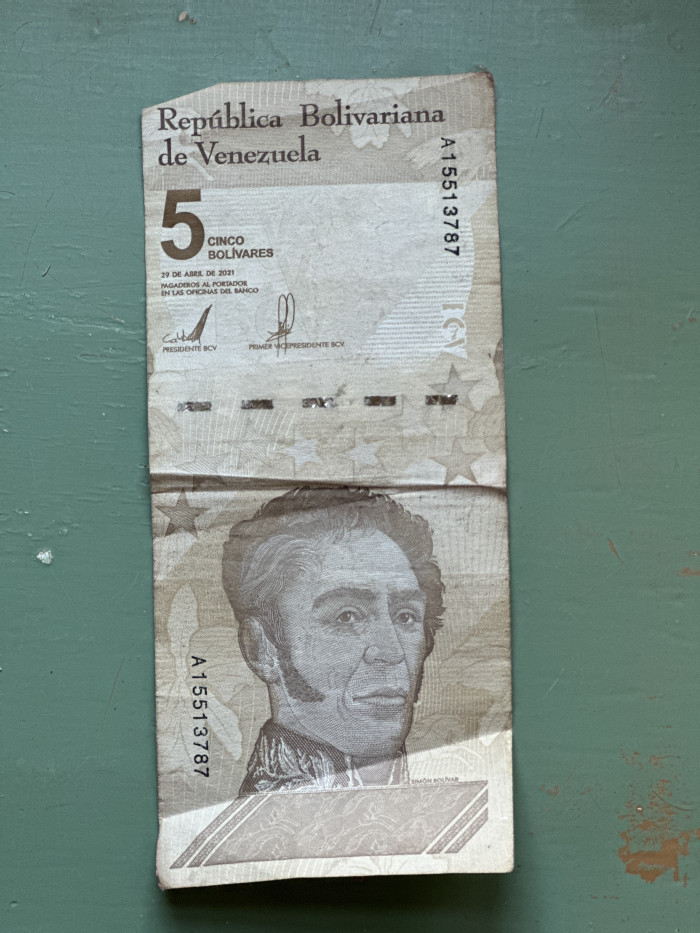

To explore the ‘local ethos’ around the bolívar and experiences of its loss of value, I am for instance considering what is called a ‘moral exemplar’ in moral anthropology. A moral exemplar is, roughly speaking, not a set of ethical rules but an admired figure through which people cultivate themselves as ethical subjects (Humphrey 1997, 25). Simón Bolívar, the Venezuelan independence warrior, can be seen as such a moral exemplar for many Venezuelans. His exemplarity stands for autonomy and self-rule, and the Venezuelan national currency bolívar is named after him (see image 1). However, exemplars do not escape moral change. In the last two decades, Simón Bolívar’s figure has been coopted by Chávez’ twenty-first century socialism. Naming his movement the Bolivarian Revolution, twenty years of chavismo came to symbolize both the region’s rejection of postcolonial forms of oppression and neoliberal dependence (Wilde 2023, 6).

In 2024 Venezuela’s dependence on natural resources has not disappeared, it has instead diversified into other networks of power and oppression, while the process of coopting Simón Bolívar resignified popular cultural attachments to him as a moral exemplar and may have made it easier to abandon a once highly valued currency.

Money and nature

Ethnographically exploring the moral experiences of worthless oil money in Venezuela benefits from a local ethic in how Venezuelans experience and make sense of a powerful myth of a regional abundance of natural resources and tremendously rich subsoils (Peters 2019; Socorro 2021; Strønen 2017). The photo I took of an artwork of a high school student in Caracas in 2023 is insightful here (see image 2). It signifies the current expanding zones of gold mining that are disrupting vital parts of the Venezuela Amazon. The use of worthless bolivares is wrapped around jumper cables as, in the words of the artist, “an intentional critique of the mining activities and the plundering that this area suffers, in the knowledge that there is an eminently economic purpose.”

This direct connection between land and money is critical to many Venezuelans. Fernando Coronil (1997, 88) has shown, for instance, how during the consolidation of the petrostate in the twentieth century, Venezuela came to be constituted not only by its people but also its main source of wealth—oil was what constituted venezolanidad. Bolívar’s liberalism became likewise grounded in Venezuela’s natural abundance and revalorized the national economic structures and social relations: citizens were not only to participate directly in national politics, but also in its natural wealth. When economies go bust the reverse appears to happen. Not only economic value, but also the moral value and affective attachment to a currency change in times of ruin. After a decade of hyperinflation, Venezuelans are now rebuilding and reevaluating their economic structures and moral relations, an outcome that is still in the making.

This text is part of the feature The Social Life of Inflation edited by Sian Lazar, Evan van Roeckel, and Ståle Wig.

Eva van Roekel is assistant professor in cultural anthropology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. She is author of the monograph Phenomenal Justice. Violence and Morality in Argentina (Rutgers University Press) and the edited volume A Collection of Creative Anthropologies. Drowning in Blue Light and Other Stories (Palgrave MacMillan).

References

Bull, Benedict and Antulio Rosales. 2020. “The crisis in Venezuela: Drivers, transitions, and pathways.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 0 (109), 1-20.

Coronil, Fernando. (1997). The magical state: nature, money, and modernity in Venezuela. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Corrales, Javier et al. 2019. “Responses to the Venezuelan Migration Crisis: A Scorecard.” Americas Quarterly July 11, 2019.

Holbraad, Martin. 2017 “Money and the Morality of Commensuration: Currencies of Poverty in Post-Soviet Cuba.” Social Analysis 61 (4): 81-97.

Humphrey, Caroline. 1997. “Exemplars and Rules: Aspects of Discourse of Moralities in Mongolia.” In The Ethnography of Moralities, edited by Signe Howell. London: Routlegde.

Laidlaw, James. 2012. The Subject of Virtue. An Anthropoogy of Ethics and Freedom. Cambridge: Cambridge Univeristy Press.

Peters, Stefan. 2019. “Sociedades Rentistas: Claves para Entender la Crisis Venezolana.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 108, 1–19.

Socorro, Milagros. 2021. “El emblema de la abudancia.: Prodavinci (September 19). Available at: https://prodavinci.com/el-emblema-de-la-abundancia/ Accessed December 21, 2022.

Strønen, Iselin Åsedotter. 2017. Grassroots Politics and Oil Culture in Venezuela. The Revolutionary Petro-State. Cham: Palgrave McMillan.

Wilde, Matt. 2023. A Blessing and a Curse. Oil, Politics, and Morality in Bolivarian Venezuela. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Cite as: Van Roekel, Eva 2024. “Money and ruin: hyperinflation and moral loss in the complex humanitarian crisis in Venezuela” Focaalblog 10 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/12/10/eva-van-roekel-money-and-ruin-hyperinflation-and-moral-loss-in-the-complex-humanitarian-crisis-in-venezuela/