During the lockdowns of spring 2020, short videos became a popular means of reflecting on new experiences of quarantine and social distancing. Passed around on social media platforms, downloaded in microseconds, and stored on smartphones where they became nested amidst other videos and photos, Corona videos brought about smiles amidst anxious circumstances and reflected meaningful forms of expert and folk knowledges about the pandemic. In this blogpost, the genre of the Corona video is approached from the perspective of anthropological filmmaking. Can anthropologists create their own cinematographic interventions into the pandemic, by joining these visual conversations while commenting on them at the same time?

Continue readingCategory Archives: Blog

Ida Susser: Covid, police brutality and race: are ongoing French mobilizations breaking through the class boundaries?

On May 31, 2020, the US exploded in protest to address the super-exploitation of racism, which has uniquely scarred its history. This was followed by international demonstrations, including massive demonstrations in Paris against police brutality, a common theme of the Gilets Jaunes, a protest starting in November 2018 that I was studying. However, this time the Paris protests included the Gilets Jaunes but focused specifically on the brutality against youth and people of color. In these important new developments, we have seen an international mobilization which may now be breaking down, or breaking through, some of the fragmentations of the working class between so-called but no longer stable working classes, the imagined middle classes also at risk of instability, and the super-exploited subjects divided by racism, sexism, colonialism, citizenship and other forms of historical subordinations.

Here I consider long-term research among street protests in France in relation to the post-Covid outrage against police brutality. Austerity policies should be seen not simply as a consequence of the Great Recession in the wake of the financial crisis but rather as the latest most destructive stage of a neoliberal assault that began worldwide in the 1970s. My ongoing research in France suggests that the mass demonstrations which began with the French Occupy movement Nuit Debout (see Susser 2016, 2017) in 2016 and continued through a variety of strikes among students, transportation workers and others until the Gilets Jaunes demonstrations of fall 2018, and finally the massive pension demonstrations of 2019/2020, represent an effort to rebalance the pendulum in the struggles against the ever more virulent neoliberal assault. These are, in the end, international processes. I suggest that the kinds of demonstrations which were emerging powerfully in France before Covid-19, are now beginning to take place in the US and elsewhere. The disastrous inequalities that were massively exposed in the unequal fatalities and economic distress caused by the pandemic (see Focaalblog: Kalb 2020, Nonini 2020) have precipitated protests that can be seen as part of an ongoing formative process.

Long-term neoliberal assault, international dimensions

Long-term neoliberal assault has precipitated the widespread destruction of a particular kind of state (Smith 2011) as well as the restructuring of global power and networks (Nonini and Susser 2020). The industrial state underwrote the corporate world by subsidizing the education, health and stability of a large proportion of workers. Twentieth century workers’ struggles established the particular forms of social reproduction originally reified in the welfare state. The idea, for example, of ‘a fair day’s wage’ encompassed the costs of the patriarchal, heterosexual family for the reproduction of men with their wives and children. However, the stable working class emerged alongside and in interaction with lower and precarious standards of reproduction for minorities, migrants and other historically subordinate groups and women, as well as the uneven development of (post) colonialism. In other words, industrial capitalism included a super-exploited working class, marked by race and gender, citizenship rights and in many cases, indigeneity (Carrier and Kalb 2015; Kasmir and Carbonella 2014; Fraser and Jaeggi 2019, Steur 2015). These groups were the subjects of distinctive historically-defined processes of inequality and they were generally excluded, especially in the United States, from the benefits of the welfare state and the class compromise.

The massive assaults of neoliberalism of the past 50 years destroyed the lives of displaced industrial workers and further devastated minority, immigrant and native communities. Under Covid-19, both in France and more drastically the US, these losses, long manifested in differential mortality rates, among others, have become immediate life and death issues.

A new working poor of displaced industrial workers compounding the super-exploitation of historically subordinated groups has been recognized in the United States and Europe since the 1990s (Susser 1996). In the shifting global power configurations, contemporary nation-states no longer protect the stability of the traditional working class. The emergence of different forms of social movements can be seen as an attempt to redress the assault on customary living conditions, life cycle security and aspirations. I would suggest that this is also an attempt to redefine workers to include the previously neglected minorities as well as new family and identity configurations. New forms of worker protection will have to consider new forms of relationships within families and new kinds of work/leisure routines to address issues that some categorize as identity politics (such as feminism and LBGT rights).

From Nuit Debout to Gilets Jaunes

After Nuit Debout, 2016-17 in France, which was largely a big city, youth led, leftist Occupy movement, the next major mobilization was that of the Gilets Jaunes (2018-2019). The Gilets Jaunes were recognized as a new phenomenon as they came from the urban peripheries of Paris and throughout the provinces. Not regarded as cosmopolitan they included many teachers, nurses, social workers as well as truck drivers, chefs, construction workers and service workers in general. Many Gilets Jaunes were middle aged and some were thought to be right wing.

Although perhaps not representative, it should be noted that the woman who sent out the first call to protest the new fuel tax implemented by President Emmanuel Macron was an educator of color from the urban periphery of Paris. In addition, contrary to stereotype and the government portrayal of the demonstrations, Gilets Jaunes insisted that they did not object to environmental concerns. They objected to a measure that targeted for extra tax the fuel that poor people in the urban peripheries were dependent on for their daily commutes. Protests were organized in collaboration with climate activists to demonstrate their common concerns and the support of the Gilets Jaunes for the environment. A frequent chant and sign stated; we care about “the end of the month and the end of the world”.

The first email call to protest the fuel tax was put out in September 2018 but by November, when the Gilets Jaunes began to block the highways and roundabouts and gather in thousands in the streets of Paris, they were objecting to much more than the fuel tax. They were concerned with the degradations of public services, the privatization of health care and their own daily challenges as well as what they saw as the decay of democracy. These protestersfrom the urban periphery frequently described the lack of investment in public transportation outside Paris and the declining support for provincial services as illustrating the “stealing of the state.” (Susser 2020). People regarded public services as a right and saw the services as belonging to the state as paid for by their tax money and therefore belonging to them. When the state privatized a service, it was seen as ‘stealing the public money.’ The destruction of the state is manifest not only in the privatization and dismantlement of public services, but also in the crisis of daily life, the family, education, health care, the aged, the handicapped (highly visible at protests on crutches and in wheelchairs) and the students, who feel they are “losing their futures,” as one protester said to me.

Continued Gilets Jaunes resistance

Until the pension strike, which began in September 2019, the Gilets Jaunes were the most powerful, and most supported of a variety of movements that had emerged in France since the austerity policies imposed in the wake of the financial crisis. They linked many of the uprisings and strikes from different sectors (such as railroads, teachers and health workers) and the smaller uprisings among hospital aides or the sans-papiers as well as the climate change activists and left-wing organizations. Not concentrated in the workplace although participating in many disparate strikes, the Gilets Jaunes invented new methods, such as the occupation of the ronds-points, the building of cabanas and the freeing of toll booths. In these ways, the Gilets Jaunes were attempting to forge a new set of resistances and generating the support of the public from the banlieues to the provinces. The movement was both enraged and resilient: Enraged at the loss of community and public and social services over time, and resilient in the commoning efforts to create a new community (Susser 2020). The Gilets Jaunes, made up of working-class people on the urban periphery, including many pensioners and families who could not make ends meet, were crafting an emerging oppositional bloc.

The pension protests began in September 2019, when strikers closed down the metro and the buses for a day. A few months later, different sectors from health care workers, legal professions, social services, educators and others, organized massive strikes and demonstrations in the streets that continued until they were shut down by the Covid 19 epidemic in March 2020.

Gilets Jaunes among the grassroots union members, in many ways, had forced the unions to take up more militant positions against the pension changes. As health workers, lawyers and transportation workers marched in massive protests through Paris, Gilets Jaunes could be seen populating the street protests of every profession in their distinctive yellow jackets, personal statements written in black marker on their backs. The signature song of all the pension protests was that of the Gilets Jaunes, as were many of the chants and banners. Until Paris was closed down for Covid-19 in March 2020, the Gilets Jaunes and the massive pension marches combined in different, often conflicted, ways across France, in some cities with more cooperation in time and place than others.

In France, Nuit Debout, the Gilets Jaunes, the pension strikers and many other movements represent transformative spaces where people in the current era of financialization and globalization are struggling to work out new strategies. Activists envision horizontalist movements as an effort to develop innovative forms of protest to counteract the increasing inequality, authoritarian tendencies and hardened boundaries of the new global regime. Such progressive representation strives for inclusivity and the breakdown and recognition of established hierarchies of gender, race, immigration and class, among others. Each of these groups has to be understood in the context of their own history and social movements. The participants in Nuit Debout were not the same as the Gilets Jaunes. However, in France and elsewhere, multiple subaltern groups may be beginning to recognize themselves as part of a larger political bloc in opposition to the destruction of the welfare state and degradation of democratic representation (Kalb and Mollona 2018). Such movements are contingent and contested, reflective of the same rage against the destruction of living standards and aspirations for a generation but offering hope for more inclusive solutions.

Before the Gilets Jaunes, in 2016/7 activists from Nuit Debout had protested the police violence often focused on young men of color in the streets. The Gilets Jaunes protested the violence of the police against their own street demonstrations for over a year. It is a crucial development that in June 2020 the Gilets Jaunes joined ranks with the protests against police brutality and racism that were rocking the world. At this conjuncture, after the shocking Covid-19 shutdown and the disproportionate deaths of people of color in France as elsewhere, the displaced workers of the urban periphery joined directly with the superexploited immigrants, refugees and previously colonized people of color from the banlieues in several unprecedented massive demonstrations.

As Polanyi knew, rage against the disastrous failures of (neo)liberalism could be expressed in brutal and fascist ways (see also Maskovsky and Bjork-James 2020, Kalb and Halmai 2011). However, the protests that we see today are a hopeful sign in their inclusive progressive moments bringing together many groups who are all at risk in different ways and at different levels or aspects of exploitation. They are demanding a rebalancing of the destructive neoliberal assault of the past 50 years. They are constructing an inclusive but uneven critical community which may serve as an antidote against the growing fury which is fueling nationalism and exclusivism (see also Kalb and Mollona 2018).

Ida Susser is Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Her most recent book is The Tumultuous Politics of Scale, co-edited with Don Nonini.

References

Fraser, Nancy and Rahel Jaeggi. 2018. Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory. Medford, MA: Polity

Carrier, James and Don Kalb (eds.) 2015. Anthropologies of Class: Power, Practice and Inequality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kalb, Don and G Halmai (eds.) 2011. Headlines of Nation, Subtexts of Class: Working Class Populism and the Return of the Repressed in Neoliberal Europe. Vol. 15. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Kalb, Don and Massimilliano Mollona (eds.) 2018. Worldwide Mobilizations. New York: Berghahn Books.

Kasmir, Sharryn and August Carbonella (eds.) 2014. Blood and Fire. New York: Berghahn Books

Kalb, Don 2020. Covid, Crisis and the Coming Contestations. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/06/01/don-kalb-covid-crisis-and-the-coming-contestations/

Maskovsky, Jeff and S. Bjork-James (eds.) 2020. Beyond Populism: Angry Politics and the Twilight of Neoliberalism. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press

Nonini, Don 2020 Black Enslavement and the Coming Agro-Industrial Capital. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/07/03/don-nonini-black-enslavement-and-agro-industrial-capital/

Nonini, D. and I. Susser (2020). The Tumultuous Politics of Scale. New York: Routledge.

Smith, Gavin (2011). Selective Hegemonies, Identities, 18(1): 2-38.

Steur, Luisa (2015). Class trajectories and indigenism among agricultural workers in Kerala. In: Carrier J and Kalb D (eds) Anthropologies of Class: Power, Practice and Inequality. Cambridge: CUP, pp.118-130.

Poperl, Kevin and Ida Susser (1996). “The Construction of Poverty and Homelessness in US Cities.”Annual Review of Anthropology 25 (1): 411–35.

Susser, Ida (2018) Inventing a Technological Commons: Confronting the Engine of Macron, http://www.focaalblog.com/2018/04/19/kevin-poperl-and-ida-susser-inventing-a-technological-commons-confronting-the-engine-of-macron/

Susser, Ida (2017). Introduction: For or Against the Commons?, Focaal 79:1-5.

Susser, Ida (2017). Commoning in New York City, Barcelona and Paris: Notes and observations from the field. Focaal 79: 6-22.

Susser, Ida (2020, forthcoming). “They are stealing the state”: Commoning and the Gilets Jaunes in France. In: Urban Ethics Moritz Ege and Johannes Moser (eds.). New York: Routledge.

Cite as: Susser, Ida. 2020. “Covid, police brutality and race: are ongoing French mobilizations breaking through the class boundaries?” FocaalBlog, 3 December. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/12/03/ida-susser:-covid,-police-brutality-and-race:-are-ongoing-french-mobilizations-breaking-through-the-class-boundaries?/

Samuel W. Rose: Disconnected Development Studies: Indigenous North America and the Anthropology of Development

The purpose of this work is to examine and elaborate on the relationship between the people of Native North America and the material and ideological content of developmentalism as examined within the fields of anthropology and Native American or Indigenous studies. I observe that Indigenous North American peoples are frequently excluded from discussions of economic development within anthropology. I try to reconcile this situation and reinsert native peoples into the anthropology of development by demonstrating the historical and political continuities between United States Indian Policy with the exported ‘development apparatus’. In doing so, I follow Neveling (2017) and others in pushing back against postdevelopment’s dematerialization of development and its emphasis on development as discourse. Instead, I argue that a historical materialist or political economic approach (Rose 2015, 2017, 2018) that conceptualizes development in the terms of Neveling’s (2017) “political economy machinery” better explains the situation of Indigenous North American peoples and the processes that make and unmake their lives.

The overall point here is that in order to properly understand the political economic basis and ideological dimensions to the Post-War developmentalism project it is necessary to understand and examine the history of those political economic models and the history of those ideological dimensions. While there likely were developmentalist antecedents in the policies of the European empires, a major distinctive feature of post-war developmentalism is that it was rooted in the political economy and hegemonic position of the United States. As such, it is crucial to understand the local antecedents for American developmentalist policies, which necessarily brings us to Indigenous peoples as they were the early laboratories of these policies and political economic models.

Contextual Disconnect

On the global level, the sub-discipline of the anthropology of development has flourished in the last half century, along with the interdisciplinary field of development studies. In that time, prominent anthropological works have been produced within the sub-discipline that have had a broad impact within anthropology and influence beyond their own regional and disciplinary scope. Some of these classics include the works of Arturo Escobar (1995), James Ferguson (1990), Akhil Gupta (1998), David Mosse (2005), and Tania Murray Li (2007). These works describe the transformative effects of ‘development’, especially on the role of state policies, on the regions formerly grouped together as the “Third World” (i.e. Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Latin America), which are now more conventionally referred to as the global South. The field of the anthropology of development, along with the interdisciplinary field of development studies, has remained almost exclusively “Third World” focused. Chibber (2013) observes that this isolation in the form of the lack of thorough comparative engagement between capitalist development in Western Europe and capitalist development in the Third World has led to an inaccurate and romanticized portrayal of each in postcolonial studies of Third World development. While I generally agree with Chibber’s critique, I wish to move into a different context. The anthropological literature on development in the global South is also disconnected from the anthropological literature on what would otherwise be called ‘development’ in what was at one time called the “Fourth World” (i.e. stateless nations), especially in regard to Indigenous peoples in North America. This disconnect actually goes both ways. Jessica Cattelino’s (2008) book is likely the most popular anthropological work on Indigenous economic development in Native North America in the last several decades. Even though her ethnography on (capitalist) economic development within the Seminole Nation of Florida was published after the texts of those aforementioned prominent anthropology of development authors, and deals with many similar issues around development such as the intricacies and problematics of sovereignty, governmentality, and possible alternative modernities, she does not utilize them or the other work from this subfield. Furthermore, Tania Murray Li’s (2010) comparative discussion of the relationship between capitalism and dispossession in different regions does not include Native North America despite the lengthy and ongoing history of dispossession of Indigenous peoples in North America in relation to both colonial policies of the past as well as contemporary processes of neoliberal capitalism and state (re)formation in the United States and Canada. Instead of including Native North America as another case study alongside Africa, India, and Southeast Asia, she mentions Indigenous people in the Anglo settler states (i.e. Canada, Australia, New Zealand, United States) or CANZUS countries (Cornell 2015) only once and in passing, and does so with the effect of driving a further wedge between them by saying that the processes of class differentiation were different among Indigenous peoples in those locations. Similarly, David Mosse’s (2013) summary article on the state of the subfield is telling of its geographic orientation as there is no mention of Indigenous North America at all and only a passing mention of development in Europe. The point is that these works are not drawing from and are not in dialogue with each other. There is a disconnect between anthropological studies of development in the global South with those on the economics and development of Indigenous people in the Anglo settler states even though (as I will argue) they share certain commonalities and histories.

Developmentalism and Native North America

The general scholarly consensus is that the modern ‘development apparatus’ and the pseudo-utopian vision that is the modernist-developmentalist paradigm began with the Truman administration after the Second World War, the emergence of the United States as a superpower, and actions taken within the context of the Cold War in needing to make capitalism more appealing for the (newly) former colonies in comparison to the political economic model of the Soviet Union and then later China (Ferguson 1990; Escobar 1995; Cowen and Shenton 1996; Rist 2008; Kiely 2007). As Escobar (1995: 3-4) states:

The Truman doctrine initiated a new era in the understanding and management of world affairs, particularly those concerning the less economically accomplished countries of the world. The intent was quite ambitious: to bring about the conditions necessary to replicating the world over the features that characterized the “advanced” societies of the time—high levels of industrialization and urbanization, technicalization of agriculture, rapid growth of material production and living standards, and the widespread adoption of modern education and cultural values.

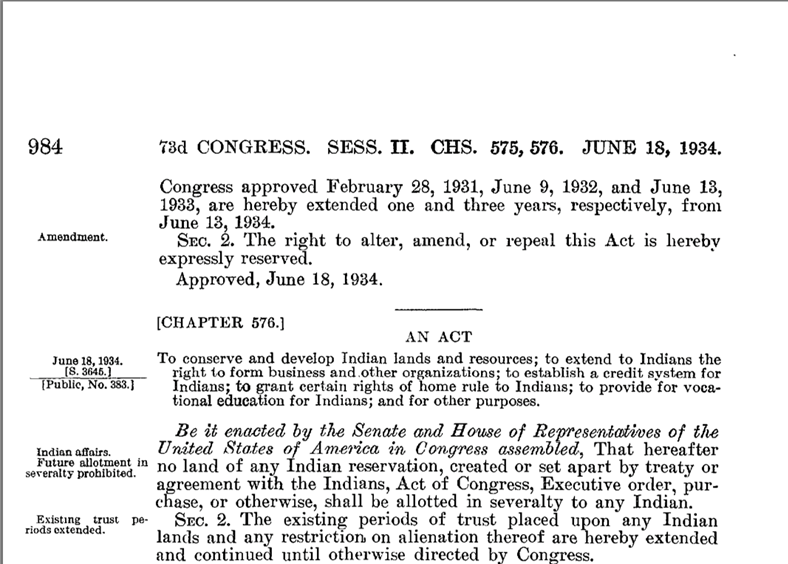

The disconnect between the subfields is especially problematic here because while the Truman administration does mark a shift in global development policy, scholars of Native North America would observe that the Truman administration also constituted a dramatic (and infamous) shift in United States Indian Policy. These two phenomena are not disconnected. When the Truman administration began exporting this pseudo-utopian vision of the glories of capitalism, technology, and Western modernity to the world, United States Indian Policy shifted away from similar policies of bureaucratization, technicalization, and industrialization for tribal governments. These policies were based around the creation and support of local/Indigenous bureaucratic institutions that would in essence aid internally in the development of Native American societies toward a form of collectively managed capitalism, which was intended to bring them as societies into the modern world. Although it had antecedents in United States Indian Policy in the nineteenth century (Miner 1989) stretching back even to the Jefferson administration’s ‘civilization’ program, this type of internal developmentalism began in a comprehensive manner with the administration of Franklin Roosevelt in the early 1930s and crystallized around the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (Jorgensen 1978). The Act, as the product of the political economy of the United States of the period, was therefore in accordance with the interests of the American bourgeoisie (Littlefield 1991), and brought about the transformation of Native American societies by formally institutionalizing capitalism within bureaucratic tribal governments. In many locations, it had the effect of solidifying political power over Indigenous communities by the emergent Indigenous bourgeoisie (Schröder 2003; Nagata 1987; Ruffing 1979; Rose 2014).

The Truman administration marked the shift in Indian Policy away from Reorganization and towards Termination (Duthu 2008; Fixico 1986). The Termination period involved a series of policies that sought to formally complete the integration or incorporation of Indigenous peoples into the American mainstream political economy by means of subjecting them to the authority of the States, physically relocating them off reservations and to urban areas, and ending—or terminating—the political and legal standing of Indigenous governments in the eyes of the United States (Duthu 2008). In short, the Termination era represents a shift in the orientation of developmentalism for native peoples: from one where their own local bureaucratic institutions were fostered as the means to bring native people into capitalist modernity, to one where these same institutions were viewed as the impediments to their achievement of modernity. It represents a shift from the policies of internal developmentalism to an external developmentalism.

Image 1: Screenshot of 48 Stat. 984 (Pub. Law 73-383), part of the Indian Reorganisation Act of 1934 (https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/48/STATUTE-48-Pg984.pdf, taken 10 Nov 2020)

The internal developmentalist policies of Indian Reorganization bear a resemblance to the modernist-developmentalism that the United States exported to the world during the Truman administration. It is my contention that the development apparatus and the modernist-developmentalist paradigm are direct successors to the long history of United States Indian Policy and these efforts. The Truman administration’s shift to a policy of global scope meant that they were to export what is in essence the same civilizing project except they did so in the language of development and modernity. However, by the 1970s, Indian Policy would shift back toward internal developmentalism in the periphery except this time under the label of self-determination (Duthu 2008). This represents an oscillation of developmentalism in the center and in the periphery corresponding to periods of expansion and contraction of American political economy (Friedman 1994). For native peoples, internal developmentalism marks a period of peripheralization as the center contracts, while termination and assimilation mark a period of external developmentalism and reincorporation into the center as it expands.

Similarly, the geographic contexts must be comparatively examined to draw out these historical parallels to better understand the historical and contemporary dimensions of capitalist development. For example, at around the same time that James Ferguson (1990) was famously discussing the “anti-politics machine” and how development (even ‘failed’ development) is linked not simply to an expansion of capitalism but to the expansion of state power, Marxist anthropologist Alice Littlefield (1991: 219) was writing that

Studies and critiques of these major policy shifts [in US Indian Policy] have frequently noted that the assimilation policies often failed to assimilate, and that self-determination policies often failed to provide for meaningful self-determination. Looking beyond the discourse of the reformers who claimed credit for these policy shifts, it can be observed that material interests of various sectors of American capital were often well-served by the workings of particular policies.

While I recognize and agree with Neveling’s (2017) critiques of the theoretical and empirical dimensions of Ferguson’s work in his overemphasis on discourse to the exclusion of political economic context, the crucial point here for me is to understand that the underlying processes being described are not dissimilar. These two works are describing a singular process or a singular political economic machinery, except that it is occurring at different times and in different places. Ferguson is describing “development” in Lesotho in the middle to late twentieth century, while Littlefield is describing “civilization”, “assimilation”, and “self-determination” in the United States as applied to Native Americans in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Further Research

We do not have the space here to delve into a detailed examination of each of the finer points. Rather, my purpose with this piece was to try to begin to connect these disparate areas and fields of study and put them into dialogue with each other. Further comparative study would better elucidate the parallels and lines of divergence in the operation of capitalist development and the experiences of peoples within this machinery. This would lead to a greater understanding and greater insights into the history and operation of capitalist development as a global project and singular machinery.

Samuel W. Rose is an independent scholar based in Schenectady, NY. He received his PhD in Cultural Anthropology from the State University of New York at Buffalo in 2017. His dissertation was entitled Mohawk Histories and Futures: Traditionalism, Community Development, and Heritage in the Mohawk Valley. His research has focused on the indigenous populations of eastern North America, community and economic development, political economy, and issues of race, identity, and the politics of history. His work has appeared in journals such as Anthropological Theory, Dialectical Anthropology, Critique of Anthropology, and the Journal of Historical Sociology.

References

Cattelino, Jessica. (2008). High Stakes: Florida Seminole Gaming and Sovereignty. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Chibber, Vivek. (2013). Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital. New York: Verso.

Cornell, Stephen. (2015). Processes of Native Nationhood: The Indigenous Politics of Self-Government. The International Indigenous Policy Journal 6(4), Article 4.

Cowen, M.P. and R.W. Shenton. (1996). Doctrines of Development. New York: Routledge.

Duthu, N. Bruce. (2008). American Indians and the Law. New York: Penguin.

Escobar, Arturo. (1995). Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ferguson, James. (1990). The Anti-Politics Machine: “Development”, Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fixico, Donald. (1986). Termination and Relocation: Federal Indian Policy, 1945-1960. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Friedman, Jonathan. (1994). Cultural Identity and Global Process. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Gupta, Akhil. (1998). Postcolonial Developments: Agriculture in the Making of Modern India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Jorgensen, Joseph G. (1978). A Century of Political Economic Effects on American Indian Society, 1880-1980. Journal of Ethnic Studies 6(3): 1-82.

Kiely, Ray. (2007). The New Political Economy of Development: Globalization, Imperialism, Hegemony. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Li, Tania Murray. (2007). The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Li, Tania Murray. (2010). Indigeneity, Capitalism, and the Management of Dispossession. Current Anthropology 51(3): 385-414.

Littlefield, Alice. (1991). Native American Labor and Public Policy in the United States. In Alice Littlefield and Hill Gates (eds.), Marxist Approaches in Economic Anthropology (p. 219-232). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Miner, H. Craig. (1989). The Corporation and the Indian: Tribal Sovereignty in Indian Territory, 1865-1907. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Mosse, David. (2005). Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. New York: Pluto Press.

Mosse, David. (2013). The Anthropology of International Development. Annual Review of Anthropology 42: 227-246.

Nagata, Shuichi. (1987). From Ethnic Bourgeoisie to Organic Intellectuals: Speculations on North American Native Leadership. Anthropologica 29(1): 61-75.

Neveling, Patrick. (2017). The Political Economy Machinery: Toward a Critical Anthropology of Development as a Contested Capitalist Practice. Dialectical Anthropology 41(2): 163:183.

Rist, Gilbert. (2008). The History of Development: From Western Origins to Global Faith, 3rd Edition. New York: Zed Books.

Rose, Samuel W. (2014). Comparative Models of American Indian Economic Development: Capitalist versus Cooperative in the United States and Canada. Critique of Anthropology 34(4): 377-396.

Rose, Samuel W. (2015). Two Thematic Manifestations of Neotribal Capitalism in the United States. Anthropological Theory 15(2): 218-238.

Rose, Samuel W. (2017). Marxism, Indigenism, and the Anthropology of Native North America: Divergence and a Possible Future. Dialectical Anthropology 41(1): 13-31.

Rose, Samuel W. (2018). The Historical Political Ecological and Political Economic Context of Mohawk Efforts at Land Reclamation in the Mohawk Valley. Journal of Historical Sociology 31(3): 253-264.

Ruffing, Lorraine Turner. (1979). The Navajo Nation: A History of Dependence and Underdevelopment. Review of Radical Political Economics 11(2): 25-43.

Schröder, Ingo W. (2003). The Political Economy of Tribalism in North America: Neotribal Capitalism?. Anthropological Theory 3(4): 435-456.

Cite as: Rose, Samuel W. 2020. “Disconnected Development Studies: Indigenous North America and the Anthropology of Development.” FocaalBlog, 17 November. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/11/17/samuel-w-rose-disconnected-development-studies-indigenous-north-america-and-the-anthropology-of-development/

Fiona Murphy: Irish State to seal records of Mother and Baby Homes for 30 years: Urgent call for action

Tiny bodies, the remains of little children entombed without name or mercy, are uncovered in Tuam, a small Irish town in Co. Galway in the west of Ireland, at the site of a former Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in 2017. The excavation, part of a Mother’s and Baby’s Home commission of inquiry (set up in 2015), precipitated by the tireless research of a local historian Catherine Corless, uncovered an eerie underground structure demarcated into 20 chambers (possibly a sewage tank) containing the children’s remains. The commission stated that ‘multiple remains’ were found, but some estimates run as high as in the region of 800. The home was run by the Catholic Bon Secours order of nuns from 1925 to 1961, one of many on the island of Ireland at that time. Now in Oct 2020, even before the Commission of inquiry publishes their long-delayed report (original deadline Feb 2018 due now Oct 30th, 2020), the Irish State has stated it intends on sealing the Mother and Baby records for 30 years.

Continue readingNicole Weydmann, Kristina Großmann, Maribeth Erb, Novia Tirta Rahayu Tijaja: Healing in context: Traditional medicine has an important role to play in Indonesia’s fight against the coronavirus

The first two cases of COVID-19 in Indonesia were announced on 2 March 2020, quite late compared to other countries. The first patient was a 31-year-old woman who came into contact with a Japanese citizen – who later tested positive – at a dance event in South Jakarta. She then passed it on to her mother. Both women were hospitalized in North Jakarta, which later became one of the referral hospitals for COVID-19 cases in the city. By early May, the number of confirmed cases nationwide had reached 9800, including 800 deaths. While elsewhere around the world governments are easing lockdown restrictions, in Indonesia there is still minimal testing being undertaken and the COVID-19 pandemic is showing little sign of decline.

As in many other nations, Indonesian politicians have been accused of not recognizing the seriousness of the situation early enough, and some eventually admitted to misinforming the public. Sophia Hornbacher (2020) only recently highlighted the populist rhetoric and neo-liberal policy of the Indonesian government, which once more illustrates the country’s problems of social injustice and welfare. In a statement made in early March, the health minister Terawan Agus Putranto said he was surprised by the commotion arising from the spread of COVID-19, as in his perspective “flu is more dangerous than the corona virus”.

In mid-April, 46 health workers at a hospital in Semarang were infected after patients had not revealed their travel history from areas with a high number of infections, or coronavirus red zones. Six weeks after the first case of COVID-19 was announced and in the face of what looked like becoming an uncontrollable pandemic in Indonesia, Lindsey and Mann summed up what many Indonesia watchers around the world and indeed Indonesians were feeling – that the government had been in denial of the health threat for too long and a clearly structured approach on how to handle infections and sources of these infections was still missing.

Crisis in healthcare

For some time there has been rising criticism of Indonesia’s public healthcare, including the closeness of pharmaceutical industries to medical practitioners and related “unhealthy practices” of corporate theft with government backing. Now, the existing structural and personnel shortage in the public health system has become glaringly stark due to the pandemic. The latest World Health Organisation (WHO) data shows that Indonesia’s ratio of doctors per 10,000 people is 3.8, and it has 24 nurses and midwives per 10,000 people. This is well below Malaysia’s 15 doctors per 10,000 people and Thailand and Vietnam’s eight. Besides this, questions about pharmaceutical monopolies and cartel practices in the medical sector, and cases of malpractice and fraud at the expense of patients, are mounting. Underlying this mood is a latent mistrust not only of the pharmaceutical industries, the medical profession, and the medical structures of hospitals, but of the national elites in general and the civil servants of health-related authorities in particular (Weydmann 2019: 60).

Recent history offers some good reasons for why medical professionals, patients and those watching Indonesia’s health sector are wary. In 2006, during the H5N1 pandemic crisis, or bird flu as it was commonly known, Indonesia claimed “viral sovereignty” and refused to cooperate with the WHO, going against a 2005 international health regulation on responsibilities and rights of national governments when dealing with a public health emergency. The contentious issue was around samples of H5N1, which were collected within Indonesia’s borders. In their analysis of this debate, Relman, Choffnes and Mack observed that the government declared “it would not share them until the WHO and high-income countries established an equitable means of sharing the benefits (particularly, the vaccine) of the sample collection” (Mack, Choffnes & Relman 2010: 27). Against this background many have reservations about the level of cooperation that can be reached between the WHO and Indonesia’s government in handling the current pandemic.

Many parties in the weeks and months to come have already criticized the emergency strategy of the government and the national health care system. We want to shed light on another issue raised by the COVID-19 pandemic, that of medical pluralism in Indonesia and different approaches to illness and health, as the medical context is critical for understanding the government’s response..

Jamu will do?

During the initial phase of the pandemic, some Indonesian policy makers claimed publicly that COVID-19 infections could heal without intervention, as long as a person’s body had a strong resistance to disease. For this reason, they reminded the public to maintain or boost levels of body immunity. President Joko Widodo supported this assessment and recommended that citizens drink traditional herbal jamu remedies to prevent infections.

In order to understand the political play on the role of jamu during the pandemic, it is important to know that the consumption of herbal plants as medicine has been part of Indonesian culture for thousands of years (Beers 2001), mainly based on oral traditions and without systematic canonization. Jamu isoften produced by households of jamu gendong sellers, who carry bottled remedies in baskets or via bicycles or motorbikes to customers.

Today, however, jamu is no longer the medicine of the poor but an economic sector with large international companies such as Air Mancur, Djamu Djago or Nyonya Meneer producing a variety of jamu remedies sold as instant powders, tablets or capsules. Street vendors compete with big drugstores over jamu sales and the Indonesian government campaign for jamu as a remedy against Covid-19 supported an important “economic pillar for the nation” (Prabawani 2017: 81) that generated IDR 21.5 trillion (US$1.38 billion) in 2019; up 13.1 percent from Rp 19 trillion in 2018.

Image 1: Jamu Gendong with trademark label on her Caping Gunung (traditional hat) (Erny Mardhani, 2020)

As early as mid-March, the Singapore-based newspaper The Straits Times reported that the President posted a statement on a government website saying that he started drinking a mixture of red ginger, lemongrass and turmeric three times a day since the spread of the virus and was sharing it with his family and colleagues. He claimed he was convinced “that a herb concoction can ward against being infected with the coronavirus”. His statements on the use of jamu medicine contributed to a rapid price increase so that prices of red ginger, turmeric and curcuma multiplied.

Like Jokowi, other politicians have pointed to the benefits of traditional medicine in the current crisis. The district health office of Situbondo in East Java invited members of his community to a public event to drink jamu medicine. He also involved hundreds of school students to further promote the benefits of the traditional medicine for strengthening the immune system. The minister for health also handed over jamu remedies to the first three recovered COVID-19 patients.

The WHO has issued a list of recommendations for handling the current pandemic, including handwashing, following general hygiene and maintaining social distancing. The early suggestions of Indonesian politicians to use herbal Jamu remedies as well as their general assessment of COVID-19 as a harmless virus, has been in clear contrast to the WHO assessment.

This approach has led to public criticism and questioning of whether politicians are intentionally withholding important information in order to avoid panic. In late March, mixed messaging from the government triggered the formation of a coalition of civil society organisations, including Amnesty International Indonesia, Transparency International Indonesia and the Jakarta Legal Aid Institute. The group urged the House of Representatives “to perform its checks and balances function during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure the government’s policies are on the right track”.

However, “healthcare” is not a singular process but consists of a complexity of different medical traditions, external influences and dynamics. As such, the ongoing COVID-19 challenge may call on different medical approaches, which are not exclusive from one another. So, whilst the WHO uses a biomedical understanding as the basis for assessing the current pandemic, Indonesia’s politicians and many citizens are turning to traditional Javanese medical paradigms. Rather than dismissing outright the calls from Jokowi and others to use traditional medicine during the pandemic, it is necessary to contextualize their calls within Indonesia’s corporate health care market as much as within the nation’s medical pluralism and the concept of traditional Javanese jamu medicine in particular.

Traditional Javanese medicine and the pandemic

The public provision of healthcare in Indonesia is almost exclusively based on biomedical treatment approaches and corresponding ways of defining health and disease. Each sub-district in Indonesia is expected to facilitate one community health center (“Pusat Kesehatan Masyarakat”, acronym: puskesmas) in order to focus on preventing diseases and promoting health. In the present COVID-19 outbreak, this has meant that puskesmas are key institutions for public health treatment and also surveillance. It is expected that each center will trace and monitor infections locally. However, puskesmas are mostly small medical units with perhaps only one medical doctor on staff. In the current crisis, these small local centers are now required to split their limited teams in order to provide public education about the pandemic, contact tracing of infected persons, and treatment of COVID-19 patients in isolation from patients with other diseases.

Indonesia, like any other nation in the world, consists of an ethnically diverse society and this social diversity is reflected in a pluralistic medical system. Large parts of Indonesian society rely on traditional medical approaches. The use of “traditional” medicine or a combination of biomedical treatment and “traditional” medicine, is a common phenomenon all over Indonesia (Ferzacca 2001; Woodward 2011, among others). Relatively recently, more educated urban households have also been found likely to use “traditional” rather than biomedical healthcare. This vivid diversity of medical traditions is represented not only in the supermarket shelves stacked with the jamu-style soft drinks promoted by the government, but also in a large informal medical market, though not in the national primary health care system.

Despite the dominance of biomedical approaches in primary health care and the accompanying skepticism towards other health etiologies, over the past 30 years the market for traditional and complementary medicine in Indonesia has experienced a veritable boom. The use of a whole range of over-the-counter (that is, non-prescription) medications, pharmaceuticals, tonics and new forms of herbal or other mixtures has sprung up, with a wide spectrum of herbal products and stamina remedies (Lyon 2005: 14).

As the COVID-19 crisis deepened, a new market emerged offering “Corona Jamu” that contains turmeric, ginger and other ingredients, in order to strengthen the body’s immune system against viruses. An existing traditional remedy, Wedang Uwuh – a herbal specialty in the region of Yogyakarta – is also being promoted, as it is used to prevent colds, warm the body and boost immunity. The remedy is composed of secang wood, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, nutmeg leaves, lemon grass roots and cardamom. The Jakarta Post summarized several reports from marketing and consumer research agencies, e.g. McKinsey, and emphasized that a number of jamu producers have seen an increase in revenue of up to 50 per cent and predicted that the habit of drinking jamu will be “a new normal”, claiming jamu as “the new espresso”. (However, no data on current market shares of small-traders and corporations in the sector is available.)

Yet, from a medical anthropology perspective, jamu consumption and prescriptions are based on the principles of humoral medicine, which has a long and sophisticated tradition. It identifies bodies as having four important fluids which are characterized as hot/cold and wet/dry, and is based on the belief that a balance of these bodily fluids is fundamental to good health. According to this understanding, a balanced unity of body, mind and spirit are essential to withstand outside influences such as viruses, evil spirits or social discrepancies (Weydmann 2019: 213ff.).

It is a long way to go for anyone to provide academic evidence that jamu medicine helps against Covid-19. And yet, some scientists now claim that the more-established traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), both traditional and modern remedies, strengthens the body’s immune system in ways that reduce viral pathogenic factors (Zhou et al., 2020). As has been demonstrated by Hartanti et al. (2020), jamu remedies promoted as Covid-19 prevention in Indonesia are adaptations of the TCM formula which has been officiated in the Chinese National Clinical Guideline as a means to prevent Covid-19 or treatment during severe and recovery stages.

While such trials and debates continue, one thing is certain. The current crisis of Covid-19 seems to be a big chance for the jamu industries. Recently, the head of the Indonesian National Agency of Drug and Food Control BPOM (Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan) declared that from January to July 2020 new permits have been distributed for 178 traditional medical remedies, 3 phytopharmaca, and 149 local health supplements with properties to help strengthen the immune system. BPOM also supports research on eight herbal products to combat symptoms of Covid-19. And, as the Jakarta Post recently wrote that there will be “a bright, post-pandemic future for Indonesian ‘jamu’” (Susanty 2020), it comes as no surprise that the Indonesian herbal products manufacturer Sido Muncul is expanding into the Saudi Arabian market as “an opportunity amid the COVID-19 pandemic”.

However, besides the economic opportunities, we also need to consider that the pandemic negatively impacts the poorest sectors of the population. Even though the Indonesian Supreme Court on the one hand annulled the increase of premiums for the National Health Insurance System (BPJS Kesehatan), Indonesian politicians are now asking the poor to spend money for jamu medications or ingredients in order to cope with Covid-19.

Against this background, the current pandemic and emerging practices of healthcare are an economic question. In short, the Covid-19 crisis “turned out to be a capitalist thing” in Indonesia as much as elsewhere (see earlier blog contribution by Don Kalb). Herbal medicine offers economic opportunities in times of crisis and even though we may dream of a system that enables health seekers to freely decide on their healthcare – independent of their economical background – we realize the many obstacles that need to be overcome before such a system can become reality for everyone.

Nicole Weydmann is postdoctoral researcher at the chair of Comparative Development and Cultural Studies with a focus on Southeast Asia at the University of Passau, Germany and works on the use of traditional and alternative medicine in Southeast Asia and Europe.

Kristina Großmann is professor at the anthropology of southeast Asia at the University of Bonn, Germany.

Maribeth Erb is an associate professor at the Department of Sociology at the National University of Singapore (NUS). Originally from the US, she has worked and lived in Singapore since 1989.

Novia Tirta Rahayu Tijaja completed her MA degree in Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Passau and currently lives in her hometown, Jakarta.

Bibliography

Beatty, A. 2002. Changing Places: Relatives and Relativism in Java. In: Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 8(3), 469-491.

Ferzacca, S. 2001. Healing the Modern in a Central Javanese City. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Hartanti, D., Dhiani, B. A., Charisma, S. L., & Wahyuningrum, R. (2020). The Potential Roles of Jamu for COVID-19: A Learn from the Traditional Chinese Medicine. Pharmaceutical Sciences & Research, 7(4), 2.

Hornbacher-Schönleber, Sophia 2020. “A Matter of Priority”: The Covid-19 Crisis in Indonesia. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/05/11/sophia-hornbacher-schonleber-a-matter-of-priority-the-covid-19-crisis-in-indonesia/. Last Access:12/08/2020.

Lyon, M.L. 2005. Technologies of feeling and being: medicines in contemporary Indonesia. In: International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter 37, 14.

Mack, A., Choffnes, E. R., & Relman, D. A. (Eds.). 2010. Infectious disease movement in a borderless world: workshop summary. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

Prescott, S. 2018. InVivo, Planetary Health: https://www.invivoplanet.com/

Susanty, F. 2020. Market reports paint a bright, post-pandemic future for Indonesian ‘jamu’. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/04/29/market-reports-paint-a-bright-post-pandemic-future-for-indonesian-jamu.html. Last Access:12/08/2020.

Weydmann, Nicole 2019. ‘Healing is not just dealing with your body‘: A Reflexive Grounded Theory Study Exploring Women’s Concepts and Approaches Underlying the Use of Traditional and Complementary Medicine in Indonesia. Berlin: Regiospectra.

Woodward, M. 2011. Java, Indonesia and Islam. Dordrecht: Springer.

Zhou, Z., Zhu, C. S., & Zhang, B. 2020. Study on medication regularity of traditional Chinese medicine in treatment of COVID-19 based on data mining. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica, 45(6), 1248–1252.

Cite as: Weydmann, Nicole, Kristina Großmann, Maribeth Erb, Novia Tirta Rahayu Tijaja. 2020. “Healing in context: Traditional medicine has an important role to play in Indonesia’s fight against the coronavirus.” FocaalBlog, 8 September. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/09/08/nicole-weydmann-kristina-grosmann-maribeth-erb-novia-tirta-rahayu-tijaja-healing-in-context-traditional-medicine-has-an-important-role-to-play-in-indonesias-fight-against-the-coronaviru/

In Memoriam: David Graeber

David Graeber: Anthropologist and Revolutionary

Continue readingVita Peacock: The slave trader, the artist, and an empty plinth

On 7th June 2020, the bronze statue of Edward Colston in the English city of Bristol was pulled down by Black Lives Matter protesters with a rope, rolled a short distance down the road, and dropped into the harbor with a gurgle. Colston was a merchant who became rich in the late seventeenth-century selling sugar, wine, oil, fruits, and most significantly, slaves from the West African coast (Morgan 1999). Although, rather dubiously, Colston left no written records, he became a member of the Royal African Company in 1680, rising to deputy governor in 1689, at a time when the chartered corporation held a monopoly over the West African slave trade, shipping captives to plantations in North America, the Caribbean, and Brazil (Pettigrew 2013). Colston’s memory has however endured in Bristol because of his local philanthropic works. Colston funded schools, hospitals, almshouses, workhouses, and other charitable causes, and even today his name is attached to a number of other toponyms across the city. The statue itself was erected in 1895 at the height of the British Empire as a tribute to these works—completely neglecting their own inhumane underpinnings.

Since the 1990s, Colston’s pivotal role in the slave trade has become more widely known, and calls had been growing to remove the statue, but without tangible effect. So when a wave of protests swept the world, in anger at the killing of African-American George Floyd by a white police officer, Black Lives Matter activists in the U.S. began upending confederate statues, and Colston fell as part of this iconoclastic surge, subsequently catalyzing it when the event was beamed across social media and made international headlines. At the time of writing, over 360 public objects across the world symbolizing racial hierarchies have now been removed, defaced, painted over, beheaded, and drowned.

Michael Taussig has reflected extensively on what happens when symbols are destroyed (1999). Public statues like the eighteen-foot figure of Colston contain a secret, a public secret—in his case the secret of African slavery that lay behind his reformist programme—that is revealed at the moment of their desecration. The power of this revelation is by its own nature temporary, but nevertheless extremely potent, releasing a ‘strange surplus of negative energy’ into the world (1999, 1), a magical shockwave whose strength is commensurate with the depth of the secret it exposes. When activist Jen Reid stood on top of the empty plinth later that day, spontaneously raising her arm in the Black Power salute, ‘It was like an electrical charge of power running through me’, she remembers. As news of the toppling continued to spread, the plinth stood there, pulsing, while a feverish debate developed over what should replace it.

The empty plinth where Colston stood is embroidered with Black Lives Matter placards (Caitlin Hobbs / 7th June 2020, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_Colston_-_empty_pedestal.jpg)

I have been an admirer of the artist Marc Quinn since I was twelve years old. That year, 1997, I was tugged along to the epoch-defining Sensation exhibition at London’s Royal Academy. Quinn’s contribution was present alongside other so-called Young British Artists, or YBAs, a new generation of creators working under the influence of postmodernism who sought to redefine what we thought of as art. The sight of his head made entirely out of his own blood is still imprinted on my mind, an object which somehow managed to capture both the intense throb of life, at the same time as being a death-mask, a memento mori. Some years later, when I was twenty, I made sure to catch Alison Lapper Pregnant on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, the sumptuous marble form of a woman in the bloom of biological reproduction alongside a severe disability.

At 4.30am on the 15th July 2020, in the space of barely fifteen minutes, Quinn, together with Jen Reid, a Guardian journalist, and a team of crane operatives, again placed himself at the forefront of my consciousness when he installed a life-sized resin statue of Reid giving her salute on top of Colston’s empty plinth, alongside a statement on his website. But this artwork raised questions in a way that the others did not.

The statement announces that it was a ‘joint’ undertaking by Quinn and his model Reid, an act of co-creation. Their aims are stated using the collective ‘we’ and Quinn stresses that he and Reid wanted to do the installation ‘together’. In a fuller interview with the Guardian, Quinn even attempts to efface his own role entirely, when he claims that ‘Jen created the sculpture when she stood on the plinth and raised her arm in the air’. But this vision of equality is a smokescreen, and a dangerous one at that. Reid did not create the sculpture when she raised her arm on the plinth, she was experiencing life as a subject, not an object, sensing the energic power of defacement. Quinn created the sculpture with a team of craftsmen. He is a white, 56-year old man, educated at a private boarding school and later at Cambridge University, with a distinguished legacy as an artist behind him. This kind of positionality does not prevent him from being the effective ‘white ally’ that the statement claims to strive for, but true allyship cannot arise when vast differences of institutional privilege are altogether erased. He announces modestly that the sculpture is ‘an embodiment and amplification of Jen’s ideas and experiences’, and yet, after trawling newspaper articles about the installation, I remain unable to answer the most basic question of Reid’s daily occupation.

Still, the most egregious part of the statement comes when Quinn asserts that the motive for the sculpture was ‘keeping the issue of Black people’s lives and experiences in the public eye’. This is at best a delusion and at worst a deception. This issue was at the very center of the public’s dilated pupils as it watched the satisfying swivel of Colston’s tumble on repeat, something which had little to do with Quinn, and everything to do with the physical, social, and legal risks taken by activists on the ground. The terrible genius of Quinn’s move was that he won either way. Either Bristol City Council opted to retain the sculpture, in which case his work would be permanently occupying what is at present the most famous plinth in Britain, or they opted to remove it, by which point the exposure achieved through the guerilla act will have inflated its capital value beyond anything that could have been achieved through more conventional means.

Of course, this was what the YBAs were known for. Tracy Emin’s soiled bed at the same Sensation exhibition in 1997 was as much a confidence trick about whether such an object could command a re-sale value as anything else. And its apotheosis came when Damien Hirst attempted to vend a diamond-encrusted skull for £50 million, a brazen (and by some accounts unsuccessful) experiment in wealth creation. Even if, as Quinn says, the money made when A Surge of Power (Jen Reid) is eventually sold will be given directly to the causes of people in Britain of African descent, the value is not his to give. Just that philanthropic gesture echoes the uncomfortable paradoxes of Colston himself, who made his wealth in an economy of exploitation only to munificently re-gift it.

‘No formal consent has been sought for the installation’, the statement says calmly. Herein lies the most problematic aspect of the work. At the risk of simplifying a complex and multivalent phenomenon (cf. Patterson 1980), we might think of non-consent as the very epicenter of the slave relation. To be compelled into a condition when the only alternative is violence or death is the antithesis of consent as we would understand it. Enlightenment thinkers invented various moral contortions to get around this brute truth, John Locke famously arguing that as captives in a just war, the slave gave his or her consent in exchange for their life, but these can now be comprehensively dismissed. To engage in such an openly nonconsensual way with a value created by Black people, both now and historically, at a time when a genuine public discussion around slavery in Britain had just opened up, was deplorable. It need not be said that if a Black artist, or someone with less gilded credentials, had engaged in this kind of illegal action, they may not have received the same general fanfare, and may even have been criminally prosecuted.

Within just twenty-four hours the artwork was removed. Bristol has been governed, since 2016, by the first ever person of African descent to be elected to the mayoralty of a major European city, Marvin Rees, whose father is Afro-Jamaican and mother is white British. Rees set the tone within hours of the installation with a public statement, ‘There is an African proverb that says if you want to go fast, go alone, if you want to go far, go together. Our challenge is to take this city far’. Quinn’s unsolicited gift, which may now be worth hundreds of thousands of pounds, was quietly, but firmly, rejected by Bristol City Council. This was no minor financial decision for an entity working under the pressure of a decade of austerity and the devastations of Covid-19. The profound dignity of this gesture was what Audra Simpson might call a ‘refusal’ (2014), a negation of one world for the purpose of affirming another. It was a refusal in this case to play the game of appropriation, the seizure of value. It gave hope for the future.

Vita Peacock is an anthropologist and Humboldt Fellow affiliated with LMU Munich and the Humboldt University. She is currently finalizing a manuscript based on her ethnography of the Anonymous movement, Digital Initiation Rites: The Arc of Anonymous in Britain.

References

Morgan, Kenneth. 1999. Edward Colston and Bristol. Bristol: Bristol Branch of the Historical Association.

Patterson, Orlando. 1982. Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge, [Mass.] ; London: Harvard University Press.

Pettigrew, William. A. 2013. Freedom’s Debt: The Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Simpson, Audra. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham: Duke University Press.

Taussig, Michael T. 1999. Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Cite as: Peacock, Vita. 2020. “The slave trader, the artist, and an empty plinth.” FocaalBlog, 29 July. www.focaalblog.com/2020/07/29/vita-peacock-the-slave-trader-the-artist-and-an-empty-plinth/

Richard H. Robbins: The Economy After Covid-19

Richard H. Robbins, SUNY Plattsburgh

One feature of both the economic recession of 2007/2008 and the present Covid-19-induced economic collapse is increased central bank bouts of quantitative easing. The U.S. Federal Reserve, after pumping about $500 billion in the economy in 2008 is adding $2.3 trillion as of April 2020, while the European Central Bank (ECB) launched a €750 billion asset purchase program in March. And the IMF estimates that global fiscal support to counter the economic effects of the pandemic is $9 trillion. The question is who gets it and what does it tell us about today’s political economy and what happens next (see also on this blog: Don Kalb 2020a)?

Continue readingDon Nonini: Black Enslavement and Agro-industrial Capital

Don Nonini, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Insa Koch’s recent (2020) FOCAAL blog, “The Making of Modern Slavery in Austerity Britain,” reminds us that enslavement and the bodies of black people are profoundly interconnected, and the link to challenges to “the punitive turn” and police abuse in the UK by the Black Lives Matter movement protests are all but explicit in her piece. At the same time, other recent FOCAAL blogs have dealt with the connections between the Covid-19 pandemic and contemporary global capitalism.

Black enslavement and Covid-19 are intimately intertwined. The insurgency of Black Lives Matter during the months of May-June 2020 has its own dynamics. That said, the wide turning out of protests supporting Black Lives Matter in the streets of European cities and towns (London, Paris, Berlin, Stockholm, Amsterdam, Antwerp, Brussels, Milan, Kraków, Dublin, Manchester, Munich…) demonstrates that the European left has strongly shown its ongoing antiracist solidarity with African-American struggles, seeking to come to terms with Europe’s own troubled imperial history of enslavements, and challenging its current neo-nationalist or fascist resurgence under declining neoliberal capitalism (Kalb 2020).

The links between black enslavement and Covid-19 start – and continue with – the formation of agro-industrial capitalism and its relations to transnational finance capital.

The Lash, Degraded Ecologies, Finance

There is a clear relationship between the emergence of modern enslavement and the history of a full-blown agro-industrial capitalism. The close connections between fully rationalized capitalist agrarian production, finance, and slavery are only recently becoming clear.

New research on the North American southern plantation economies shows just how advanced rationalized capitalist production was under the conditions of slavery (Baptist 2014). Beyond its monocropping ecology, “many of agribusinesses’ key innovations, in both technology and organization, originated in slavery” (Wallace 2016: 261). Slaveholders measured land only against the capacity of slave labor to transform it, setting the cotton production line in terms of “bales per hand,” with enslaved African men being “hands,” nursing mothers “half hands” and children “quarter hands.” The labor process of picking cotton was measured and held to a standard by another unit of measurement – the “lash.”

“Enslavers used measurement to calibrate torture in order to force cotton pickers to increase their own productivity and thus push through the picking bottleneck” (Baptist 2014: 130). As Baptist further points out, “on the nineteenth century cotton frontier… enslavers extracted more production from each enslaved person every year. . . the business end of the new cotton technology was a whip” (2014: 112). Planters managed a refined rationality based on the application of the whip measured out in lashes to the backs of a slave calculated relative to their infraction – how many pounds of cotton his basket fell short of making a bale, whether or not there were impurities in it, whether one slave helped another pick her quota – in which case the former received extra lashes. Under the circumstances, the rationality of increased “labor productivity” so vaunted by economists depended straightforwardly on graduated torture – with little contribution (the cotton gin aside) from “technological innovation.”

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 culminated the violent displacement of Indian nations from the Mississippi Gulf region and transformation of their territories into “new lands” of thousands of acres ready for slave-based production (Baptist 2014: 228-229). Cotton monoculture quickly exhausted the rich soils of the South, exposed the crops to rust, rot, and worms, while plowing rows of cotton aligned to the day’s sunlight to maximize yield eroded the land and exhausted aquifers within 10 to 15 years after clearing (Wallace 2016: 266).

Due to the lack of food self-sufficiency and the seasonality of cotton harvests, indebtedness by plantation owners to Northern financiers and cotton brokers became increasingly common. By the 1830s, the cotton plantations of Mississippi, Alabama and Eastern Louisiana had adopted new forms of finance and indebtedness, when the Consolidated Association of Planters of Louisiana was established to allow their member planters to mortgage their slaves as collateral for loans from international financiers, led by the Baring Brothers and the Bank of England, that pooled investments from Europe’s finest old and new upper classes to buy the lucrative bonds issued by the Association (Baptist 2014: 245-8).

Monocropping of plants and animals, the simplification and degradation of local and regional ecologies, rapid expansion of logistics over space, reliance on finance capital for loans to expand production, and the use of enslaved degraded labor – these design features of agro-industrial capitalism have remained in effect to the present.

Meat Markets, Neo-Slave Markets

The coerced use of black labor continued after the Civil War in the cotton sharecropping economy until its decline in the 1930s. At the same time, the new agro-industrial complex of livestock production in the U.S. South – again based on the hyper-exploitation of black labor – got underway. By the 1970s, the livestock industries of intensive hog, poultry, and beef production had become thoroughly institutionalized – through vertical integration (Heffernan and Constance 1994; Stiffler 2005), increases in slaughterhouse assembly-line tempos, and incorporation of meat eating as a universal practice within the diets of the U.S. population (Schlosser 2001, 2012; Stiffler 2005). Since the 1990s the meat industries have globalized to penetrate the BRICS economies, a process facilitated by the lubrication of capital provided by hedge funds and investment banks, such as Goldman Sachs’ deal-making in the sale of Smithfield Foods to Shuanghui in China (Wallace 2016: 269-271).

Subjugated and coerced black labor has anchored and offered up surplus value through U.S. agro-industrial cotton and meat production since the end of legal slavery. Since the 1960s, rural poor African-Americans, especially women, have worked in the meat processing plants of the Midwest, Mississippi delta and Carolinas regions experiencing intensified exploitation, sexual harassment and brutalized and unsafe working conditions. By the 1990s, they were joined by immigrant Mexican and Central American workers (Nonini 2003; Stiffler 2005; Stuesse 2016), with whom white plant managers sought to set them in competition.

The Great Migration of 6 million African-Americans from 1915-1970 from the South to cities in the northern and midwestern U.S. was a form of flight from re-legalized enslavement at the hands of Jim Crow whites. Migration to the Midwest and Northeast placed large numbers of blacks at the factory doors of the Fordist industries of the North. Relegated to secondary labor markets by discrimination from white industrial labor unions during the 1950s-1970s (Cowie 2010: 236-244), black industrial workers by the 1990s, like their white counterparts, were thrown out of work by the globalization of industrial production. The only exceptions were the neo-slavery of hyper-sweated meat processing and related industrial food labor.

“Broken Windows Policing” and the Expropriation of Black Lives

The grown children and grandchildren of these laid-off black industrial workers, with more recent Latinx immigrant workers, now form both the hyper-exploited workers in the food industries (meat processing, fast foods, farm work) and situated in the cities and small towns of the South, Midwest and the Northeast, and those who are chronically unemployed and underemployed, doubly discriminated against due to their poverty (forcing them to leave school before high school graduation), and their race. Those African-Americans who have more or less steady employment also show disproportionate levels of consumer debt – from credit cards, student loans, and medically -related debt. Whether steadily employed or not, a key insight is that by and large both groups draw on the same population of urban African-Americans.

The population of urban African-Americans has the profound misfortune of living in cities recurrently subject to gentrification at the new “urban scale” of globalized real estate and finance-rentier capital (Smith 2008: 239-266). Their residence in spaces made newly desirable by gentrification by the 2000s is the obverse of the fact that up to the 1990s whites fled inner cities in large numbers for segregated suburbs, while African-Americans found themselves only able to afford to live, and only allowed to live within, housing in these redlined inner-city districts.

By the 2000s, however, real estate in these districts had become “hot properties” for global finance capital seeking new sites for safe but extraordinarily profitable rent collection and property speculation in realizing value. This trend by the 1990s was both shaped by and reinforced through the “broken window policing” that targeted unemployed and underemployed African-Americans and Latinx populations (Camp et al. 2016).

What precisely is the role of broken windows policing in the gentrification process? Put non-too-subtly, even one broken window indicates the existence of a “criminal” – an undesirable element in a neighborhood. The role of such policing is the physical removal to jails or prison, or, if that is impossible, the destruction of African-Americans whose very presence threatens the “real estate values” that the finance industry and its local allies hold dear. This goes far to explain the more than 1000 people killed by local police every year in the US, of whom more than one fourth are African-American; the one third of African-American men between ages 19-35 who are “justice involved” – in jail awaiting trial, on bail, undergoing trial, in prison, on probation or parole; and their disproportionate representation in the US’s incarcerated population, the largest per capita in the world.

Nancy Fraser (2016) observes that there is an historical dialectic between the conditions that set out “normal” exploitation of the working force, and the conditions of expropriation of the lives, labor, and property of racialized and vulnerable (e.g. immigrant) populations — as two complementary means through which the accumulation of capital can and does take place under capitalism. Fraser argues that that the new being of neoliberal global capitalism is “the expropriable-and-exploitable citizen-worker,” and that “the racialized subjection of those whom capital expropriates is a condition of possibility for the freedom of those whom it exploits” (Fraser 2016:163).

We can see these two modes of appropriation of surplus value in the tense interconnections between whites and the African-American population in the United States through the latter’s vexed history with respect to agro-industrial and finance capitalism. These interconnections are potentially the point of class differentiation between the increasingly precarious white “middle class” and urban African-Americans, who straddle a black employed working-class subjected to intensified exploitation on one hand, and a lumpen-proletariat subjected to police-impelled expropriation and dispossession, on the other.

Ongoing criminalization and the indebtedness of black people (the latter a tool of finance capital’s domination) are the instruments driving large numbers of urban black workers disproportionately employed in the agro-industrial food sector toward the toxic mix of indebtedness, unemployment (where employers often refuse to hire blacks holding consumer debt), bankruptcy, evictions from shelter, police “stop and frisk” harassment, enforced fines and fees levied (via police and private firms working for straitened municipalities), assault, imprisonment, and death (Wang 2018:99-192).

Don Nonini is Professor of Anthropology at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His most recent books are “Getting by”: Class and State Formation among Chinese in Malaysia (Cornell, 2015), and The Tumultuous Politics of Scale: Unsettled States, Migrants, Movements in Flux, co-edited (Routledge, 2020). His most recent publication in FOCAAL is “Theorizing the Urban Housing Commons” (2017).

References

Baptist, E. E. (2014). The half has never been told : slavery and the making of American capitalism.

Camp, J. T. and C. Heatherton (2016). Policing the planet : why the policing crisis led to black lives matter.

Cowie, J. (2010). Stayin’ alive : the 1970s and the last days of the working class. New York, New Press : Distributed by Perseus Distribution.

Fraser, N. (2016). “Expropriation and exploitation in racialized capitalism: A reply to Michael Dawson.” Critical Historical Studies 3(1): 163-178.