“On the form, I ticked that I had got enough pads. I ticked that I had been instructed. I ticked that I had applied for microloans, more than once. I ticked that I had been encouraged. I ticked that I had nowhere to live. I ticked that I had nowhere to study. I ticked that I had nowhere to go. I ticked that I had nothing to lose. I ticked that I didn’t mind the NGO using my personal data for their future projects.”

This quote is an excerpt from a Sashko Protyah short story, where a citizen of Mozambique makes a deal with a people smuggler. The business offers an innovative method of (post)human trafficking, promising to turn their clients from the Global South into a bird, and flying them to European shores, where they can regain human form and continue their way to the European Union. To her ill fortune, the protagonist reaches European land in Mariupol, Ukraine, in the spring of 2022, when the Russian invasion of the city was in full force. Eventually, she manages to escape with a group of volunteers who evacuate pets from the occupied territory, but her transformation fails, and she is caught in a netherworld between being animal and human, with no acceptable form, identity or document to prove her belonging to any official entity. Falling through the cracks of state assistance, she is approached by humanitarian NGOs that work in the conflict zone and recruit vulnerable people for well-worded but questionable development projects. In the end, the protagonist is hired in an “apocalypse theme park” that recreates the siege of Mariupol as an infotainment experience, engaging the visitors with authentic scenarios of explosions, looting, and no running water.

The author of the short story, Sashko Protyah from the Freefilmerz art collective was one of the speakers at the workshop “REMEMBERING / RECLAIMING / RECONSTRUCTING SPACE: Working with local heritage in times of war and displacement” I organized at the University of St Andrews as a knowledge exchange event during my ESRC Postdoctoral Fellowship., The workshop invited Ukrainian cultural practitioners working with precarious heritage during the Russian invasion to share their experiences with a group of international researchers studying similar topics. Besides broadening our knowledge about pragmatic aspects of heritage work in the context of war, the short lectures delivered by Ukrainian participants highlighted a set of ethical issues equally relevant in the work of ethnographers and other researchers working with vulnerable communities.

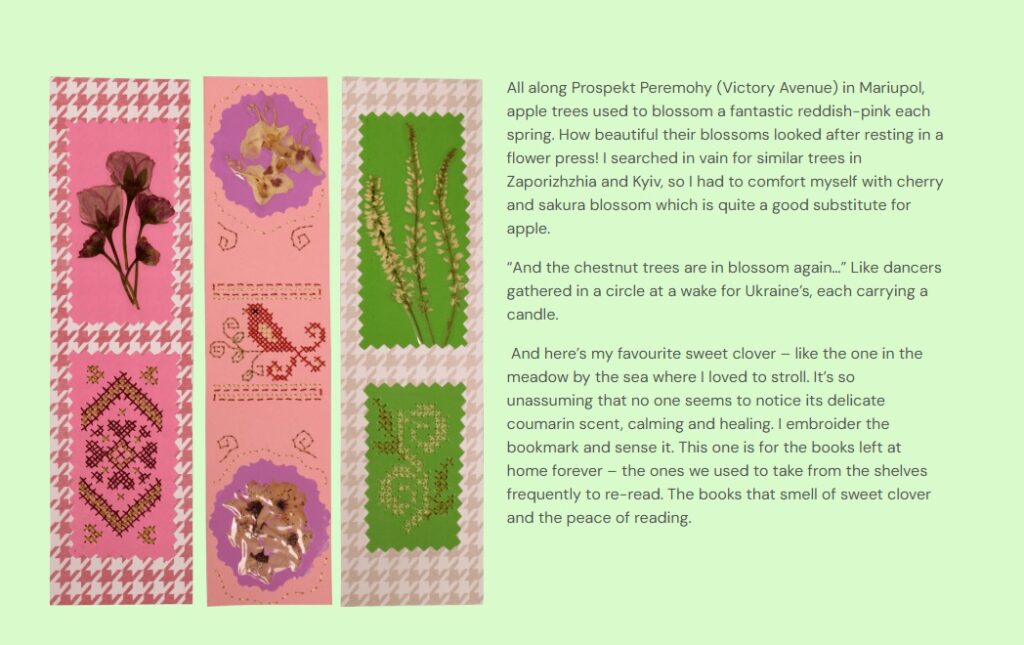

Protyah talked about his experience of creating Mariupol Memory Park, an online archive that commemorates and celebrate life in Mariupol. The website collects testaments about the city from a variety of authors in different genres, all of them affectionate while reflecting the multivocality of urban life and the complicated emotions elicited by the place. As Sashko pointed out, and his short story addresses in a critical self-reflexive manner, one of the major risks of creating this kind of archives is the exploitation of traumatic memories. Since the start of the full-scale invasion, refugees from Mariupol and other places have been asked on countless occasions by journalists, researchers, NGO workers and others to share their experiences of war and displacement for various projects. While these conversations require significant temporal and emotional investment from the participants and can have a re-traumatizing effect, interlocutors are rarely compensated or offered psychological support. The dynamics of this exchange reflect a deeper running process that Asia Bazdyrieva (2022) termed the “resourcification of Ukraine”, referring to the continuing tendency of Western and Soviet geopolitical thinking to reduce Ukrainian land and people to a “resource that qualifies for a long list of services.”

The idea of resourcification, when applied to people, recalls long-standing conversations in anthropology regarding the inequality of researcher and interlocutor. Even in times more peaceful than the current moment, academics need to confront the dilemma of waving goodbye to our interlocutors and returning to Western institutions to advance our careers using the knowledge they have shared with us, leaving them with… what exactly? In a context of war or other forms of violence, this situation gets complicated by concerns about personal safety, stigmatization and psychological trauma, reiterating the question: on what ground do we expect people to share their most difficult life experiences with us? How do we make participation beneficial for them in the short as well as the long term? What is our role as researchers in a time when the communities we work with are fighting for survival?

While in certain cases, interlocutors think about sharing traumatic experiences as a politically or psychologically important act of giving a testament or gaining recognition of the injustices they have suffered (see Veena Das’ essay “Our work to cry: Your work to listen” (Das 1990)), the expectations of the research relationship can also become a source of frustration to the members of “over-researched and underserved” (Yotebieng 2020) communities.

Mariupol Memory Park addresses the problem of exploitation by commissioning new works to construct an archive, shifting the emphasis from the extraction of painful memories to the process of creation and reflection. Contributors retain the agency to tell their story in a way they feel appropriate instead of being used as information sources or credibility props in someone else’s project. Importantly, they are all paid for their work from the funding received by Western European NGOs and government research agencies.

In anthropological practice, financial compensation for research participation is rarely used due to issues around voluntary consent and authenticity of information. However, this should not discourage academics from contemplating the place of money in supporting interlocutors, especially in a time when communities face the ongoing existential threat of war and genocide. One way to do this is acknowledging the role of participants as co-creators and channelling institutional funding to financially honour their contribution. Another avenue might involve collaborative projects with local organizations using research funding from Western institutions. Area studies professor Victoria Donovan (2023) evokes the figure of the “trickster” to propose a strategy for academics to facilitate this process within the often rigid institutional hierarchies, suggesting “using the power (and, crucially, the funding) that we are assigned to manifest the changes that we want to see.”

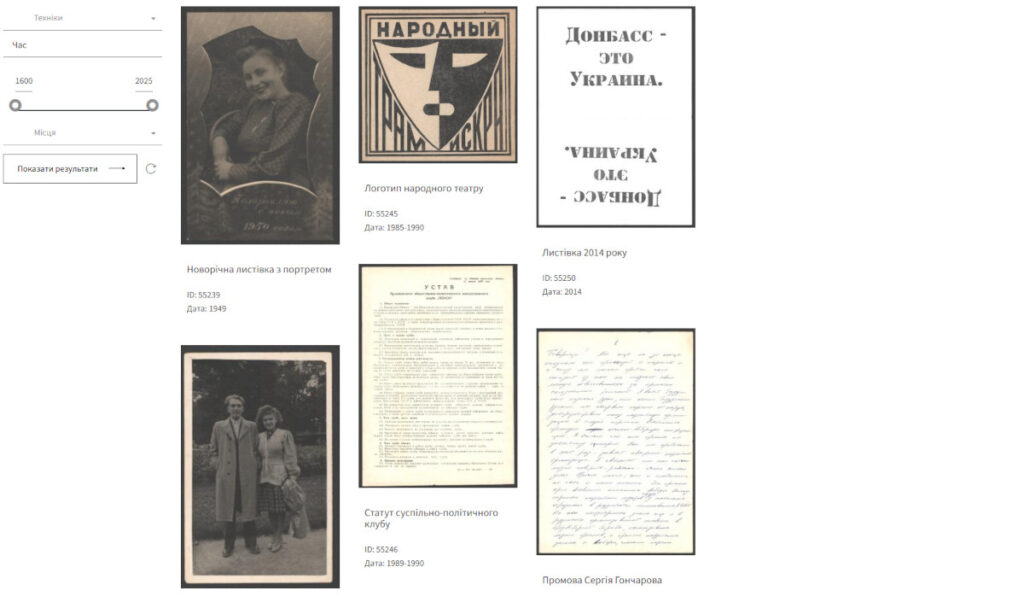

Approaching the theme of collaboration from another angle, Kateryna Filonova from Mariupol Local History Museum and Iryna Sklokina from Lviv Center for Urban History presented during the workshop their initiative City in the Suitcase: Saved (Family) Archives. The project addresses the problem of museum heritage lost in the war due to physical destruction, looting, and the logistical problems created by relocating whole museums from the occupied territories. Attempting an alternative route to reconstruct lost local heritage, the curators published a call inviting residents from occupied cities of Eastern Ukraine to share their family photography collections. The call, while it received valuable material, had a relatively low response rate. Having worked with IDPs from the Donbas since 2014, Kateryna from Mariupol Local History Museum remarked that this was more or less expected: the experience of the previous ten years suggests that people who need to flee in a hurry do not prioritize taking family albums. As a result, the call received less material from Mariupol, and more from other places where residents had more time to prepare evacuation. The other limitation of the entries is related to the specific status of digital media in contemporary conflicts. While digital data becomes more important in conditions of material destruction and displacement, as people are often left with their phone memory as their only source of personal photos, phones and social media accounts were thoroughly examined by Russians at the military checkpoints. As a result, several people had to delete their photos and apps on the road, and many of them got locked out of their accounts, losing access even to the digital memories they had left.

In the end, the project received eighteen collections of family photography from different cities of Eastern Ukraine. The material collected this way offers “an alternative history of the Donbas”, featuring elements of Ukrainian culture, the democratic movement of the 1990s, as well as the pro-Ukrainian and Anti-Maidan demonstrations of 2014. Discussing the potential of representing “history from below”, Iryna emphasized the importance of reflexivity in their curatorial practice. Archives are instruments of power, and the decisions made by the archivist determine what story will be told for future generations of historians and the public. In the case of personal collections, the curators paid extra attention to avoid imposing their own interpretations while processing the data according to archival standards. To achieve this, they employed what they call a “non-institutional approach to documenting”, archiving what respondents chose to include and annotating the material in a continuous conversation with the owners of the photos. At the same time, they emphasized that the owners’ interpretation was also situated, reflecting their current position in relation to the post-independence political history of Ukraine.

Lessons from the project City in a Suitcase reiterate the idea that there is no “view from nowhere” during the creation of an archive (Zeitlyn 2012), making it inevitable to reflect on the position of each stakeholder. For an anthropologist, such an approach evokes familiar debates on reflexivity in social research. Both in archival and anthropological practice, discussions on reflexivity question the neutrality of knowledge produced within a hegemonic system of institutions by members of privileged social groups (Al-Masri et al. 2021). Restructuring the research process into an act of co-production, as it happened with the contributors of the photo archive, offers a way to decolonize the hierarchical relationship between the knower/known (Casagrande 2022).

The last major theme emerging during the workshop was the relationship of traumatic memories and global heritage regimes. The “apocalypse theme park” described in Sashko’s short story is an exaggerated version of memory parks that turn places of collective trauma into profitable tourist attractions, disregarding the needs of the affected communities (Meskell 2002). As Sashko said, similar projects are already taking place in relation to Mariupol, and it is important to speak up against the commodification of people’s loss and sorrow. However, as it was abundantly demonstrated in recent years in Ukraine, Gaza and elsewhere, the destruction of cultural heritage is not simply a by-product of contemporary warfare, but an integral part of genocide and cultural erasure (Tsymbalyuk 2022). The “dark heritage” of such cynical and calculated destruction demands a tactful approach of representation that allows the world to learn about what happened while prioritizing the needs of community members. Discussing the case of the 9/11 memorial in Manhattan, Lynn Meskell observes a growing “desire for grounded materiality” (Meskell 2002) in a moment when the broader public collectively encountered the experience of a virtually broadcasted, real time terror attack for the first time. The present context of urbicide and displacement can evoke a similar longing for tangible markers of commemoration, presenting the challenge to find new ways of representation that avoid commodification and the creation of genocide-disneylands.

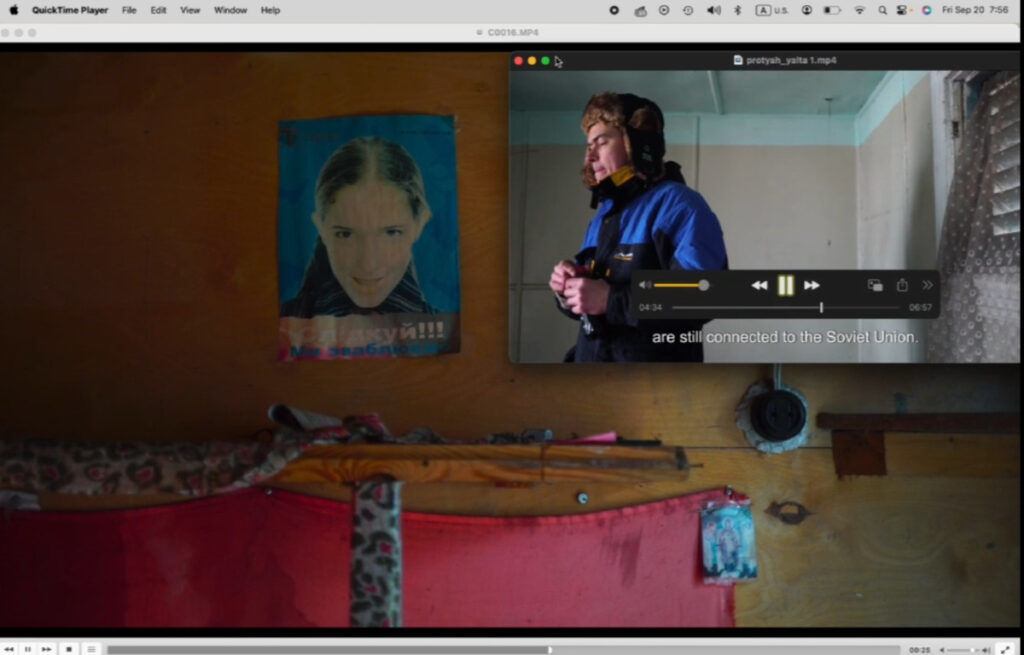

The work of Oksana Kazmina, another member of the Freefilmerz art collective, offers a possible answer to this dilemma. Contemporary History of Ukraine is a series of “performative walks” composed of digital media fragments: video footage, online maps, zoom recordings and photos are combined on the screen to (re)construct landscapes of memory. In the virtual walk created for the workshop, Oksana explores the transformative potential of the “yebenya”, a concept denoting a place of abandonment and decay in the East European urban typology. Walking through the ruins of a former Soviet pioneer camp in a coastal village near Mariupol in 2018, she contemplates the role of these material structures in making sense of the past and our own place in it. “Maybe we did need these places of abandonment, which are also traces of how things used to be. We needed them to be conserved like this for us to come here and look in the mirror.” Similarly, to the debris of Soviet urban infrastructure, material traces of violence have a potential beyond erasure or sensationalism: approached with care, they can serve as an object of reflection in the difficult process of making sense of experiences that should have never occurred.

The initial aim of the workshop was to explore the strategies Ukrainian cultural workers use to address unprecedented experiences of destruction, displacement and trauma. The resulting dialogue about extractive humanitarianism, the commodification of traumatic heritage, and the politics of representation has shown alarming resonance with the geopolitical developments of the recent weeks. As I am finalizing this text, the Trump government has stopped all military and most of the humanitarian aid to Ukraine, while working out the details of a blatantly late-colonialist and exploitative rare minerals deal that would push the country further into economic deprivation. The projects presented during the workshop are highly critical regarding the role of Western assistance in local cultural practice. In the current circumstances, their critique offers a constructive alternative to the deliberate dismantling of vital support networks in the region.

The workshop was supported by ESRC UK (grant ID: ES/X006182/1). Video lectures by Ukrainian participants were commissioned and each speaker was paid an honorarium for their work. Many thanks to Sarah and Sandra from the Research Administration team of School of Philosophical, Anthropological and Film Studies at University of St Andrews for their help.

Anna Balazs is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, Södertörn University, Stockholm. She received her PhD in social anthropology at the University of Manchester in 2020. Her work focuses on the infrastructural and cultural legacies of socialism in Eastern European cities, and the temporalities of geopolitical conflict in Ukraine. The present text was written during the ESRC Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of St Andrews, UK.

References

Al-Masri, Muzna, Samar Kanafani, Lamia Moghnieh, Helena Nassif, Elizabeth Saleh, and Zina Sawaf. 2021. ‘On Reflexivity in Ethnographic Practice and Knowledge Production: Thoughts from the Arab Region’. Commoning Ethnography 4 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.26686/ce.v4i1.6516.

Casagrande, Olivia. 2022. ‘Introduction: Ethnographic Scenario, Emplaced Imaginations and a Political Aesthetic’. In Performing the Jumbled City: Subversive Aesthetics and Anticolonial Indigeneity in Santiago de Chile. Manchester UK: Manchester University Press.

Das, Veena. 1990. ‘Our Work to Cry: Your Work to Listen’. In Mirrors of Violence: Communities, Riots and Survivors in South Asia, 345-399. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Meskell, Lynn. 2002. ‘Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology’. Anthropological Quarterly 75 (3): 557–74.

Tsymbalyuk, Darya. 2022. ‘Erasure: Russian Imperialism, My Research on Donbas, and I’. Kajet Digital (blog). 15 June 2022. https://kajetjournal.com/2022/06/15/darya-tsymbalyuk-erasure-russian-imperialism-my-research-on-donbas/.

Zeitlyn, David. 2012. ‘Anthropology in and of the Archives: Possible Futures and Contingent Pasts. Archives as Anthropological Surrogates’. Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (Volume 41, 2012): 461–80. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145721.

Cite as: Balazs, Anna 2025. “War, displacement, and cultural heritage: reflections on a workshop” Focaalblog 18 March. https://www.focaalblog.com/2025/03/18/anna-balazs-war-displacement-and-cultural-heritage-reflections-on-a-workshop/