Cuba is currently facing one of its most severe economic crises in decades. The island nation is contending with the compounded effects of a global pandemic, tightening U.S. sanctions, and its own mismanaged monetary reforms, all of which have created a perfect storm of high inflation, scarcity, and social unrest. As the Cuban peso (CUP) loses value at a rapid pace, Cubans are increasingly turning to alternative currencies and unconventional economic activities to survive. Among these, play-to-earn crypto games like Axie Infinity have emerged as an unexpected source of income, offering a connection to the global digital economy for those who do not have access to remittances from abroad. However, the game’s economic model, which requires significant initial investment and relies heavily on exploitative “scholarship” arrangements, ended up reinforcing pre-existing social inequalities rather than addressing them. Moreover, Axie Infinity faced severe inflation issues itself, with the in-game currency devaluing rapidly due to an oversupply. Over time, its structure began to resemble the characteristics of a Ponzi scheme, where new investments were needed to sustain returns for existing players. This forced players to navigate an increasingly unstable digital economy, where opportunities for profit were outweighed by rising risks.

To understand the emergence of play-to-earn games as a significant economic practice in Cuba, we must first grasp the current economic landscape. Cuba’s economy has been hit hard by several overlapping crises. The Covid-19 pandemic brought tourism—the country’s economic backbone—to a near standstill. Concurrently, U.S. sanctions, particularly those tightened under the Trump administration, restricted remittances, cut off access to international financial systems, and further isolated Cuba from global financial flows.

Internally, the Cuban government’s decision to implement the Ordenamiento Monetario in January 2021—intended as a comprehensive monetary reform—eliminated the longstanding dual currency system that had kept the economy afloat. Before this reform, the Cuban peso (CUP) was used for domestic transactions and salaries, while the dollar-pegged convertible peso (CUC) was used for tourism, luxury goods, and international trade, which allowed the government to control access to foreign currency and manage economic disparities. By making the CUP the sole legal tender and devaluing it against the U.S. dollar, the reform triggered runaway inflation. The artificially low exchange rate of the CUP against the dollar could not be sustained, leading to a spiraling devaluation of the national currency.

Amid the financial turmoil, many Cubans are turning to alternative currencies to protect their savings in more stable forms and to manage everyday transactions. Cryptocurrencies, particularly USDT, a stablecoin pegged to the U.S. dollar and (theoretically) backed by dollar reserves, have gained significant popularity as a tool for receiving remittances and facilitating cross-border payments. Meanwhile, digital credits—ranging from balances on apps like Zelle and Tropipay to phone credits—emerged as vital tools within Cuba’s expanding informal economy. During the pandemic, the Cuban government introduced its own digital currency, the moneda libremente convertible (MLC), pegged to the dollar and meant to serve as a substitute for foreign currency in state-run stores selling essential goods. The MLC was specifically designed to capture hard currency for the state, as it could only be acquired through foreign currency deposits or remittances. However, as its acceptance became limited to a shrinking number of outlets and a thriving black market developed for exchanging MLC into other currencies, its value eroded, declining sharply against both the U.S. dollar and digital credits denominated in dollars on payment apps.

The Currency Black Market: A Disorderly Landscape

This monetary disorder has led to a burgeoning informal market for currency exchange, which operates largely through digital platforms like Telegram and WhatsApp. Here, Cubans negotiate the value of dollars, euros, MLC credits, and various cryptocurrencies, often using intermediaries to facilitate exchanges. elTOQUE, an independent news outlet based in Miami, has become a key player by publishing the informal exchange rates of these currencies daily. These rates are determined by bots scraping buy and sell offers from major Telegram groups, yet they remain contentious, with frequent accusations of manipulation, particularly from the Cuban government.

In this chaotic environment, cryptocurrencies offer another refuge from the collapsing Cuban peso, but they also introduce new complexities, particularly in converting digital assets into usable cash. Many Cubans now use stablecoins like USDT to preserve value and facilitate international payments, while digital platforms have become essential tools for managing remittances and cross-border transactions. However, the real challenge lies in bridging the gap between these digital currencies and local cash. On platforms like Telegram and Revolico, brokers facilitate exchanges from digital tokens to cash, often charging high fees and adding another layer of volatility and risk to an already unstable financial landscape.

Gaming the System: How Axie Infinity Became an Economic Lifeline

Amid Cuba’s ongoing inflationary crisis, an unexpected means of accessing digital tokens emerged: play-to-earn crypto video games like Axie Infinity. Developed by the Vietnamese company Sky Mavis, Axie Infinity allows players to breed, battle, and trade digital pets known as Axies, which are unique digital assets or non-fungible tokens (NFTs) stored on the blockchain, enabling players to own, trade, and speculate with their in-game holdings. The game broke into the mainstream in many low- and lower-middle-income countries in the summer of 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. It became a widespread phenomenon across much of the Global South, permitting players to earn substantial income in the game’s cryptocurrency, Smooth Love Potion (SLP). As global lockdowns cut off traditional jobs and informal income opportunities, the game (at least for a while) enabled players in countries like the Philippines, Venezuela, and Indonesia to earn hundreds of dollars per month—often well above their local median wage—and offering economic opportunities that their physical economies could not.

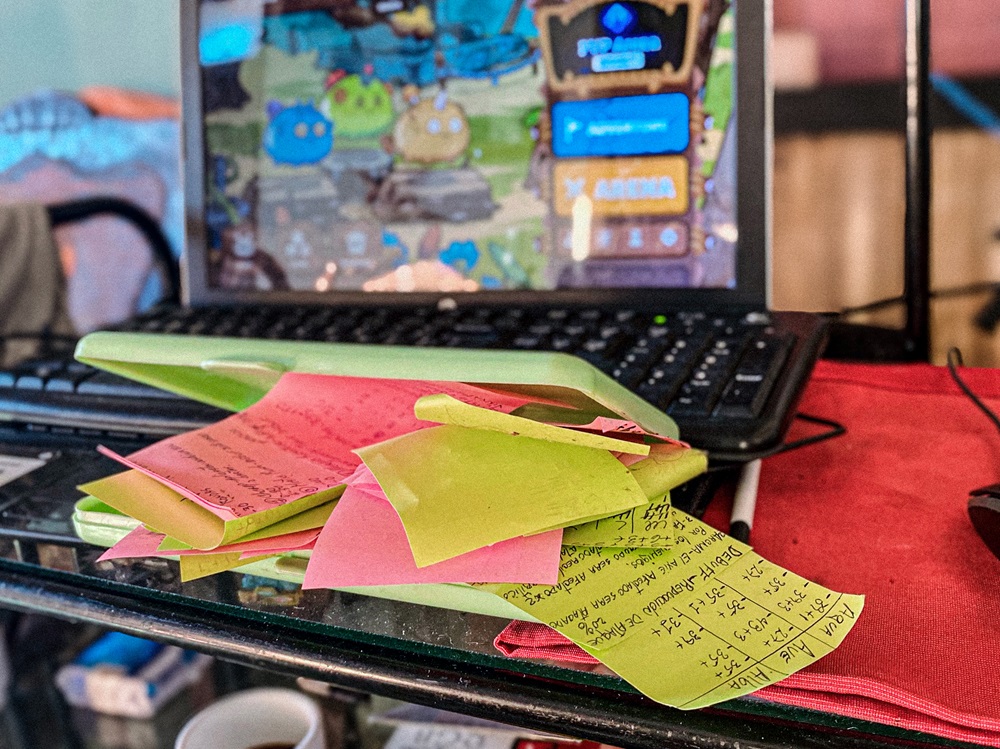

For thousands of Cubans, especially those without access to remittances, Axie Infinity quickly became a potential economic fallback. With traditional income sources disrupted by the pandemic and ongoing inflation, the game offers a rare opportunity to earn cryptocurrency, which can then be traded on the black market for pesos or other more stable currencies. However, participating in Axie Infinity is not without its challenges, and many Cuban players have had to navigate a complex landscape of intermediaries, scams, and volatile markets to turn their virtual earnings into real-world value.

The entry barrier to Axie Infinity is steep. At its peak, in July 2021, even the cheapest team of three Axies required to start playing cost around $1,000—an impossible sum for most Cubans. This led to the emergence of a parallel economy where affluent players and companies, often based in wealthier countries, granted “scholarships” to aspiring players. Gaming guilds emerged on Telegram, offering training sessions and conducting entrance exams for those seeking scholarships. These scholarships involved lending Axies to players who couldn’t afford them in exchange for a share of their earnings, often up to 70 per cent. This system allowed Cuban players to participate in the game, but it also mirrored exploitative labor practices, with the scholars—typically from the Global South—bearing the brunt of the risk while the asset owners in more developed nations took the lion’s share of the profits.

Scholars were required to play for several hours every day, with their performance closely monitored—either by coaches hired by NFT owners to provide training but also to surveil them, or through surveillance software that tracked their activity. In my friend Juan’s guild, there were even two competitive leagues, and members could be relegated like football teams. Those who failed to meet performance targets were quickly replaced by other aspiring players, reinforcing a precarious labor market marked by a harsh hire-and-fire culture. In this context, Axie Infinity’s promise of decentralized and equitable opportunities increasingly resembled a new form of digital serfdom, perpetuating existing inequalities rather than alleviating them.

Trust and Mistrust in the Cuban Crypto Economy

Beyond the game itself, Cuban players encountered significant challenges when trying to convert their in-game earnings into usable currency. Due to U.S. sanctions, centralized cryptocurrency exchanges like Binance and Coinbase block users from Cuba, forcing players to depend on informal and often opaque networks for transactions. In the Telegram currency exchange groups where Cubans from across the country participate, the primary challenge was establishing trust, as no one wanted to be the first to send cryptocurrency or fiat money and risk relying on the trading partner to follow through. This led to the development of new intermediaries and trust mechanisms. To mitigate the risk of fraud, some Telegram groups set up their own escrow systems, where admins held funds from both parties for a fee until the exchange was finalized. Other groups introduced a VIP system, granting trusted status to users with multiple successful transactions who provided personal information to the group’s administrator and paid a monthly fee. While these systems offered a semblance of security, they also underscored the inherent contradictions of a supposedly “trustless” blockchain-based economy that, in reality, relied heavily on middlemen and trust-based social networks to work.

Despite the often exploitative working conditions and the complicated process of cashing out game tokens, Cuban Axie Infinity players demonstrated considerable agency in navigating these challenges. They used platforms like Discord or Telegram to create grassroots solidarity networks, actively sharing information about scholarship opportunities and educating others on gaming strategies. This sense of community and mutual support became a crucial resource for many players striving to make the most of the game’s economic opportunities.

For many Cubans, Axie Infinity also represented a rare chance to engage in the global digital economy at a time when Cuban society had only recently come online. It enabled some players to transition from mere participants to asset owners and investors by purchasing their own Axies. Many of the players I interviewed had eventually invested in the game, buying their own digital pets and exploring the speculative potential of this virtual economy. For these players, the game marked their first encounter with a global financial market, pushing them toward speculative behavior and exposing them to its inherent risks. The SLP token—like many cryptocurrencies—proved to be even more volatile than the Cuban peso, making it a highly unpredictable asset. Nevertheless, this volatility did not deter them from hoping to strike it big; rather, it underscored the precarious yet captivating nature of their engagement with digital economies.

Precarious Play

The experience of Cuban Axie Infinity players sheds light on a broader trend in the digital economy: the merging of play, work, and investment in ways that challenge traditional definitions of labor. Concepts like “gamification” (Robson 2015) and “playbor” (Kücklich 2005) have been used to describe how game-like elements are incorporated into non-game contexts to enhance engagement or extract value. However, play-to-earn games like Axie Infinity take this a step further by directly integrating financial incentives into gameplay, creating a highly speculative and precarious form of digital work.

For Cuban players, the volatility of the SLP token added another layer of uncertainty. In the early days, some players earned substantial sums, far exceeding local wages. But as new player growth slowed after the hype in the summer of 2021, the game’s revenue—and thus the value of in-game assets—plummeted. The in-game inflation began to mirror real-world inflation: the more players sought to extract value from the game without reinvesting, the faster the currency’s value declined. When North Korean hackers stole $620 million from the game’s blockchain in March 2022, the already fragile Axie economy collapsed further, leaving many players with worthless tokens (Harwell 2022).

The Fragile Promise of Blockchain

The case of Axie Infinity in Cuba exposes the limits of the promises made by blockchain evangelists (e.g. Tapscott and Tapscott 2016, Domjan et al. 2021, Kshetri 2023). Far from bringing financial inclusion and economic empowerment to the Global South, the game’s ecosystem often reproduced existing inequalities and inflationary dynamics. In theory, blockchain technology is supposed to offer a decentralized, transparent alternative to traditional financial systems. Yet, in practice, Cuban players found themselves entangled in a web of intermediaries, trust-based networks, and volatile markets, which reinforced rather than dismantled power imbalances.

The rise and fall of Axie Infinity in Cuba provides a stark reminder of the limitations and risks inherent in new digital economies. This became especially evident when Axie Infinity’s in-game inflation eventually surpassed the inflation in Cuba’s real economy that had driven many players to the game in the first place. While the game initially offered a lifeline to some, it also exposed the precarious nature of digital work, where players are subject to volatile earnings, insecure contracts, and exploitative conditions. The experience of Cuban players thus challenges the narrative that blockchain technology will bring about a more equitable global economy. Instead, these systems can easily replicate and even exacerbate existing inequalities, creating new forms of digital labor exploitation and financial speculation.

This text is part of the feature The Social Life of Inflation edited by Sian Lazar, Evan van Roeckel, and Ståle Wig.

Steffen Köhn is a filmmaker and associate professor of visual and multimodal anthropology at Aarhus University. He is the author of: Island In the Net. Emergent Digital Culture and its Social Consequences in Post-Castro Cuba (forthcoming with Princeton University Press) as well as Mediating Mobility. Visual Anthropology in the Age of Migration (Wallflower/Columbia University Press 2016). His films have been screened at the Berlinale, Slamdance, Rotterdam International Film Festival, BFI Film Festival London, and the Word Film Festival Montreal, among others.

References

Domjan, Paul, Gavin Serkin, Brandon Thomas, John Toshack. 2021. Chain Reaction: How Blockchain Will Transform the Developing World. Basel:Springer International Publishing.

Harwell, Drew. “U.S. Links Axie Infinity Crypto Heist to North Korean Hackers.” The Washington Post, April 14, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/04/14/us-links-axie-crypto-heist-north-korea/.

Kshetri, Nir. 2023. Blockchain in the Global South: Opportunities and Challenges for Businesses and Societies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kücklich, Julian 2005. Precarious playbour: Modders and the digital games industry. fibreculture 5 (1): 1-5.

Robson, Karen Kirk Plangger, Jan H. Kietzmann, Ian McCarthy,and Leyland Pitt. 2015. Is it all a game? Understanding the principles of gamification. Business Horizons 58 (4): 411-420.

Tapscott, Don and Alex Tapscott. 2016. Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World. New York: Penguin.

Cite as: Köhn, Steffen 2024 “Tokens of survival: the rise of crypto gaming in Cuba’s inflationary economy” Focaalblog 10 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/12/10/steffen-kohn-tokens-of-survival-the-rise-of-crypto-gaming-in-cubas-inflationary-economy/

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.