In the midst of India’s extensive urbanization, with more than 34% of the population dwelling in urban areas as of 2021, as per the World Bank, the complex relationship between urban transformation, poverty dynamics, and the impact of capitalism gains prominence. Amidst this swiftly urbanizing landscape, it is relevant to ask about the enduring significance of street shrines and the deities they embody. This blog post unravels the complex interplay between urbanization, poverty dynamics, and capitalism in shaping the evolving narrative of street shrines in Delhi. By examining specific examples, we seek to contribute to the understanding of the socio-political implications of religious transformations, shedding light on the informal mechanisms that influence the cultural and political dimensions of urban India.

As Hindu deities increasingly dominate street shrines, such as those near Jama Masjid, Red Fort, and Chandni Chowk, the very essence of these spaces undergoes an accretionary conversion over time. This transformation is not merely a happenstance but a result of a complex collusion involving diverse social and economic players who shape the city’s evolving political, religious, and cultural landscape. Old Delhi, with its labyrinthine lanes and historical significance, is undergoing a palpable cultural reshaping as Hindu dominance unfolds within its streets.

Street shrines, once reflective of the syncretic blend of Hindu and Islamic traditions, are now marked by a pronounced prevalence of Hindu deities. This is largely due to the ongoing influx of labor migrants from the neighbouring states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh into the city who are reshaping the sacred spaces in both their structure and function. The diverse backgrounds, cultures, and religious practices of the migrants contribute to a rich tapestry of beliefs that find expression in the street shrines. The choice of the deities is a reflection of their faith. Migrants, seeking a sense of community and continuity with their cultural heritage, often contribute to the embellishment and maintenance of these shrines. The shrines may adapt to serve not only as religious spaces but also as community hubs where migrants find support, share experiences, and build social networks.

Icons like Shirdi Sai Baba and Hanuman, along with other Vedic motifs, have become the visual protagonists, signifying a transformative narrative that overrides the Islamic heritage that was historically ingrained in this part of the city. In the intricate lanes of Old Delhi, the evolving narrative of cultural transformation is discernible through the gradual transition of temporary religious symbols into enduring fixtures. Local spaces, once harmoniously shared, now bear markings that define them for specific purposes, subtly alienating those who traverse them and instilling a sense of unease. This shift, woven into the fabric of the city, holds profound implications for understanding the social and ethnic conflicts that manifest within its boundaries.

The multifaceted nexus signifies that as urban centers burgeon, various economic and social forces come into play, fostering both economic opportunities and disparities. The growing number of street shrines might be interpreted as a reaction to the changing cityscape, complexly influenced by issues of poverty, capitalism, and religious practices. The chosen field sites in New Delhi were intentional selections, serving as gateways into regional politics entwined with land acquisitions, unraveling layers of influence on the transformation of public shrines and art.

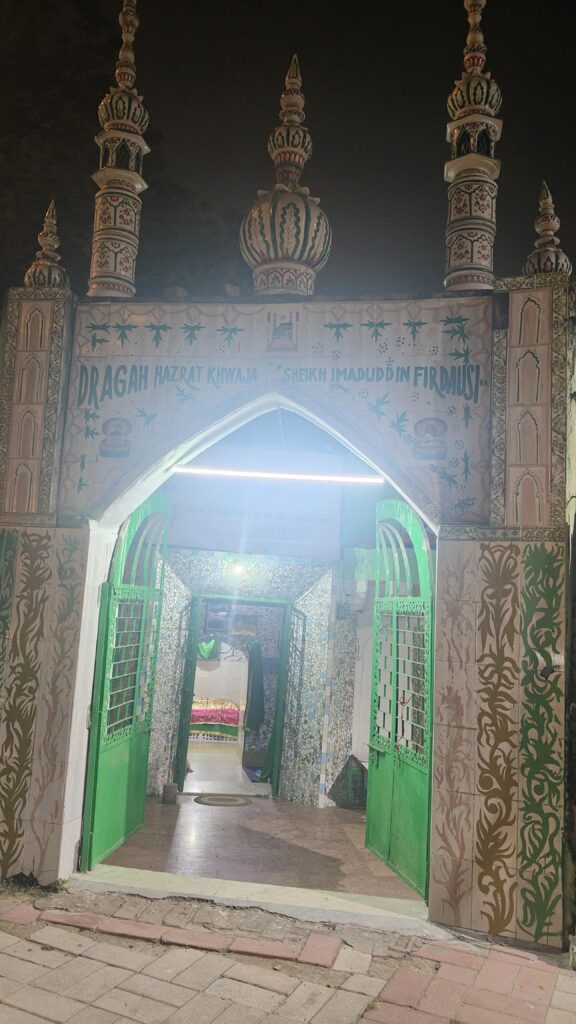

The following provides some examples of street shrines and the changes they have undergone.

Hanuman’s Ascendance: In the heart of Old Delhi, near the iconic Jama Masjid, street shrines that were once adorned with Islamic calligraphy and symbols now prominently feature the figure of Hanuman. This ascendance of Hanuman in the visual landscape signals a shift in religious and cultural prominence, eclipsing the Islamic heritage that was historically intertwined with this area.

While administrative authorities recognize that these religious shrines can be leveraged for land acquisition, the marginalized inhabitants dwelling in their vicinity perceive them as a safeguard against eviction, highlighting the intrinsic connection between religion, politics, and commerce —exemplifying the strategic integration of religious practices and turning these humble street shrines into vibrant expressions of cultural and spiritual amalgamation while at the same time legitimising the ownership of the marginalised communities residing in the slums of the capital.

Furthermore, demolition notices have been issued by authorities to mosques located on land that the Delhi Waqf Board asserts as its own. The board has filed a challenge to two of these notices in the High Court because of the Places of Worship Act 1991 of the Indian constitution, according to which a mosque, temple, church or any place of public worship that was in existence as of 15 August 1947 will retain the same religious character that it had on that day – irrespective of its history – and cannot be changed by the courts or the government. It is worth noting that these actions targeting Muslim sites transpired simultaneously with other initiatives, such as the purported demolition of dwellings in squalor areas prior to the G-20 summit that was hosted in Delhi on September 9 and 10.

Some other examples of dominance of Hindu street shrines in predominantly Muslim neighbourhoods are:

Symbolic Transformation near Red Fort: Walking towards the iconic Red Fort, another bastion of Delhi’s historical legacy, one can observe a symbolic transformation in the street shrines that line the route. Hindu deities, particularly Hanuman and Shirdi Sai Baba, now take centre stage, subtly overshadowing the Islamic architectural marvels and their associated religious symbols.

Syncretism Eroded in Chandni Chowk: Chandni Chowk, renowned for its historical syncretism, is experiencing a erosion of this syncretic cultural tapestry. Street shrines in this area, once a testament to the harmonious coexistence of Hindu and Islamic traditions, now showcase a pronounced prevalence of Hindu deities. The visual language is evolving, rewriting the narrative and erasing some of the syncretic elements that defined Chandni Chowk.

Influence in Kinari Bazaar: Kinari Bazaar, a market known for its traditional charm, reflects the broader influence of Hindu dominance in Old Delhi. Street shrines along the narrow lanes prominently feature symbols associated with Hinduism, subtly reshaping the cultural and religious landscape of this historic market.

The evolution of Hindu street shrines in New Delhi is intricate and multi-layered, intertwining individuals and households based on factors such as caste, religion, regional origin, language, or ideology. This complexity is vividly illustrated by the diverse ways in which these communities engage in political strategies, aligning themselves with various political parties. This involvement emerges as a pivotal dimension in the larger quest for social mobility and empowerment in the city.

For instance, certain street shrines may become focal points for followers supporting different political parties, reflecting the dynamic nature of political affiliations within these communities. The cultural movements and societal struggles that unfold within these religious spaces seamlessly transition into political conflicts, with tangible manifestations in territorial disputes over physical space in New Delhi. For instance, recently in Jan 2021, an idol of Shirdi Sai Baba was demolished by a BJP supporter and a realtor because a Jat Hindu Guru had claimed Shirdi Sai Baba was born a Muslim, and the realtor did not want that to be placed in a Hindu neighbourhood.

In essence, the nuanced dynamics of Hindu street shrines not only mirror the cultural diversity within the communities but also serve as arenas where political ideologies and affiliations converge, shaping the broader narrative of social dynamics and empowerment in the dynamic context of New Delhi.

It is essential to have a clear understanding of the fact that political and religious imbrications are connected to rural-urban flows, transitions, and networks, as well as the caste and regional conflicts that are involved in these transitions and connections. Furthermore, it is important to note that these imbrications are not simply the result of government action or inaction on urban and spatial planning: caste and regional conflicts are also involved.

At the same time, publicly addressing the contentious issues that arise from these conflicts and struggles cannot be addressed purely through formal state or urban planning mechanisms, as these play out primarily through informal channels, in spatial patterns that are informal, and in public spaces that through long term practice and local sanction have been earmarked for informal uses. Because politics, religion, and culture are much more closely linked in the Asian context to issues of dominance, inequality, and hierarchy – all of which operate through informal mechanisms – it is not surprising that battles around these take place in informal spaces, and perhaps even achieve a greater degree of success than formal or institutionalised attempts to democratise Indian society.

The ethnographic observations about these shrines offer a glimpse into the ongoing negotiations between tradition and modernity, the sacred and the secular, thus contributing to the broader scholarly debate on the cultural and political dimensions of urban India. The enduring legacy of these shrines, amidst the dynamic changes of urbanization, reflects not only a rich cultural heritage but also a resilient adaptation to the evolving socio-political landscape.

In conclusion, this exploration into the realms of street shrines offers insights into their evolving cultural and political significance. The dynamic mosaic of street shrines in urban India serves as a vivid representation of the intricate interplay among diverse cultural dimensions. Amid conflicting perspectives on land utilization and decision-making authority, the delineation of sacred boundaries becomes increasingly intricate, particularly in a country like India where finite land resources pose challenges. This ethnographic journey seeks to unravel how these sacred spaces engage with the dynamic geography of the city, thereby reshaping the ancient Islamic architecture in Delhi’s urban landscape.

Dr. Smytta Yadav is an Anthropologist and currently a Leverhulme Research Fellow at the University of Sussex. The above article is an output of her AHRC grant number AH/T000864/1 which she held at the Queen’s University of Belfast. The title of the grant was Ancient Vedic Gods in Early Urban and Pre-Mughal India.

References:

Kennerly, R. M. (2005). Roadside Shrine Cultural Performance: Poststructural Postmodern Ethnography. Agricultural and Mechanical College, LSU.

Mayaram, S., Pandian, M. S. S., & Skaria, A. (Eds.). (2005). Muslims, Dalits, and Historical Fabrications (Vol. 12). Oriental Blackswan.

Cite as: Yadav, Smytta 2024 “Shifting Landscapes: Urbanization, Religious Transformations, and Cultural Resilience in Delhi” Focaalblog 16 January. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/01/16/smytta-yadav-shifting-landscapes-urbanization-religious-transformations-and-cultural-resilience-in-delhi/

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.