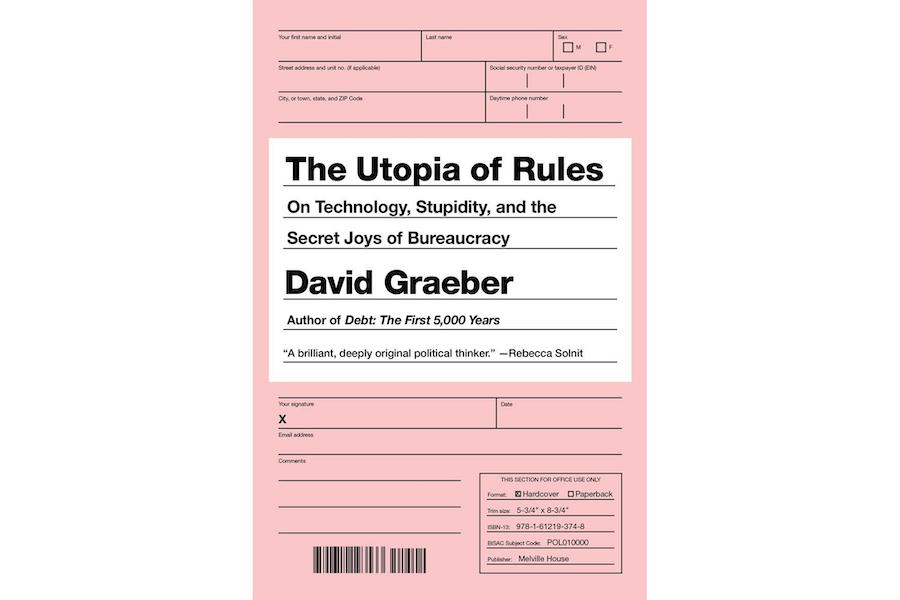

David Graeber’s wide-ranging – and, appropriately, sometimes wildly swashbuckling – set of essays sketches his anarchist utopia by default, as a social world free of bureaucracy. Bureaucracy, he writes, is “stupid” and “absurd.” Stupid or otherwise, it represents the effect of a vast and powerful set of forces operating through the mechanisms of the modern state, of which the United States is both example and exceptional case. Its goal, in Graeber’s gloomy vision, is to destroy the stability and viability, both social and economic, of entire populations, while congealing ever larger portions of the world’s wealth into ever fewer hands; its stupidity lies in refusing all alternative interpretations to official Diktat (see especially pp. 80-81). Graeber largely ignores bureaucracy’s many non-state versions, a choice that reflects a bias toward current American uses of the term. Instead, he plays creatively and contrastively with the British self-view as anti-bureaucratic (p. 13). This distinction nevertheless entails excessive generalization and elides differing historical trajectories. It is hard now to write critically of Graeber’s provocative thought, grounded as it was in an uncompromising search for social justice and a becoming modesty about the originality of his own ideas, without sounding petty. The significance of his many projects, however, demands both generosity and critique.

To that end, it seems useful to begin by asking whether stupidity rather than (perhaps deliberate) tautology or ritualism, the latter explicitly acknowledged by Graeber (p. 50; see also Hinton 1992; Herzfeld 1992), is the basis of bureaucracy. In many societies, a clear distinction is made between sly cunning and intelligence of morally neutral (or even foolishly innocent) stamp (e.g., Schneider 1969). In his eagerness to debunk the crasser versions of pseudo- or meta-Foucauldian analysis, which at least attribute agency to state operators, Graeber seems to discount the slyness of those bureaucrats who realize that getting people to monitor themselves furthers the state’s rather than the public’s interests. As I have recently noted, the complexity and unpredictability of the various national COVID-19 testing requirements force nervous international travelers to monitor their own actions with ever-increasing unease (Herzfeld 2022a). Graeber also overlooks the helpfulness of some bureaucrats, who may even – indeed, often do – collude with their clients by shifting the interpretation of the rules.

Graeber does distinguish between the system and its operators, but one might wish for a more detailed exploration of where the two diverge. He tells us very little about how agile operators actually bend the system to meet their own and their clients’ exigencies – apparent exceptions that may actually confirm his argument since, by generating a sense of the obligatory gratitude of client to patron, they further weaken resistance to encompassing bureaucratic structures. This is implicit in his argument, but his broad generalizing prevents readers from seeing how the wiliness actually works. Within the utopia of rules, continual adjustment occurs in the form of supposed illegality lurking in the very implementation of legality (see, e.g., Little and Pannella 2021). Graeber’s observation (p. 214) that legality is born of illegal actions is also historically consistent with the crisis of legitimacy posed by the persistence of rebellious forces claimed as heroic forebears by nationalistic state regimes (see Herzfeld 2022b: 39-40). Graeber does nevertheless expose some real cunning, notably when he points out the discrepancy between the virtually flawless operation of ATMs and the deeply flawed operation of American voting machines (p. 35). It is hard to believe, he suggests, that such a glaring discrepancy could be unmotivated; both trajectories serve the same general politico-financial interests.

Graeber is on firmer (because more explicit) ground when he suggests an analogy, albeit an inverse one, between bureaucracy and Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism: whereas bureaucratic logic suppresses insight, the equally narrow and schematic analyses of the structuralist master open up exciting new paths. This is surely a more productive comparison than dismissing one system as stupid and the other as genial. Both systems are concerned with classification, one to impose it and the other to decode it. But Lévi-Strauss would never have dismissed indigenous taxonomies as stupid; nor would any anthropologist since Malinowski have considered such a characterization as other than the expression of a colonial and racist contempt for “the Other.” In rightly up-ending power by treating bureaucracy as the Other, Graeber nevertheless refuses it the minimal respect that he surely would have demanded of his students for the taxonomies of other cultural traditions.

It is here that his activism seeps into his anthropology and exposes, as he surely must have desired, the difficulty of trying to do anthropology, especially activist anthropology, in one’s own milieu and at such an inclusive level. While calling bureaucracy stupid seems epistemically retrograde, it may eventually facilitate new political insights – if, that is, someone undertakes the necessary ethnographic labor. The gap between insight and demonstration is one of several tensions exposed, but not necessarily resolved, in Graeber’s book. Some of his more speculative leaps of faith are persuasive – but I found myself wondering whether that was simply because I was already predisposed to agree, and what unexpected subtleties a more ethnographic approach might introduce.

Graeber’s claim that technological advances were deliberately advanced by a capitalist cabal evilly intent on reducing humanity to a collective serfdom does appear to be on target for the period he describes. He provides convincing examples of how specific technologies, poised to take off in directions anticipated by science fiction and other fantasy literatures, have clearly faltered. Whether this remains true – whether his account is more than a conspiracy theory – has perhaps become more questionable even in the short time since his death. More problematic still is his confident attribution of collective intent on the part of neoliberal capitalists to condemn the entire world to servitude. While it is apparently true that during the current pandemic the super-rich have vastly increased their wealth while the numbers of the truly poor in the U.S. alone have soared (see Luhby 2021), the idea of a concerted intentionality risks reproducing precisely the kind of conspiracy theories that favor right-wing panic-mongering (although, unlike the latter, it stands a reasonable chance of eventual vindication). Here, too, he implies an unprovable ability to read collective minds. Moreover, I am unsure that animals are incapable of “creating self-conscious fantasy worlds” (p. 171). Indeed, how can he be so sure?

Such problems typically arise when anthropologists shift from familiar engagements with ethnographic detail to grapple with the big picture. Graeber, an anarchist activist for social justice, was skilled in both practices, but in this book the big picture, along with the speculative reasoning that it tends to generate, predominates. Although educated in the U.S. in what is there called cultural anthropology, and despite his scathing (and largely well-conceived) critique of “globalization,” Graeber does not attend to cultural differences that may affect bureaucratic habits. While too generously acknowledging my own study of bureaucracy, he complains that virtually all the anthropologists who have written about bureaucracy “almost never describe such arrangements as foolish or idiotic” (pp. 237-38n42; cf. Herzfeld 1992). There is, as I have just indicated, good reason for this apparent omission.

With regard to mind-reading, anthropologists do often report on a range of emotional reactions, from astonishment to contempt, that their informants display toward bureaucratic arrangements. It is expressed attitudes that they describe, not innermost thoughts. Indeed, they often also note their informants’ reluctance to read minds (Robbins and Rumsey 2008). The reported reactions and the accompanying skepticism are ethnographically revealing to a level that Graeber’s broad-brush descriptions of capitalism, bureaucracy, and globalization do not always achieve. His description of globalization, in particular, sweeps over cultural differences that – as, for example, James L. Watson (2006) argued so lucidly for consumption in Asian McDonald’s restaurants – may significantly affect how we understand the local significance of apparently global phenomena.

In this sense, all bureaucratic practices must be understood in terms of cultural values shared by bureaucrats and their clients. That argument also fits Graeber’s excellent debunking (pp. 166-174) of bureaucracy’s claim to pure rationality. When one side makes excuses that its interlocutors might indeed view as lamentably stupid, the other side accepts them, not necessarily because they are believable, but because they are conventional. They are a means for both sides to manage otherwise difficult situations, their effective performance always, from one situation to another, mediated by the tension between the conventions for excuse-making and the inventiveness of those involved. This illustrates what I have called “social poetics” (e.g., Herzfeld 2016), a concept that in some respects fits nicely with Graeber’s focus on imagination (see especially his illuminating analogy with the structure and playfulness of language, pp. 199-200, a passage that beautifully exemplifies the important but often-forgotten principle that an explanation based on language does not necessarily reduce all social phenomena to discourse).

An effective bureaucrat – though not necessarily a good one – manages, while appearing to insist on rigid adherence to the rules, to operate them with considerable ingenuity and, yes, imagination. Graeber barely considers the extent to which bureaucrats must deploy the unspoken local social rules in addition to the “stupid” requirements of the official system. While such seesawing between convention and invention is apparently common to all state bureaucracies, the specific modalities may vary enormously. The unfinished task Graeber has bequeathed to his successors is the ethnographic exploration of high-end bureaucratic management. Cultural specificities will loom large in such studies – all the more critically inasmuch as the managers invoke supposedly universal principles to justify their actions.

Let me illustrate with a simple example. During early sojourns in the Netherlands, I found an unsmiling bureaucracy that seemed obsessed with observing the rules. Gradually, however, I learned that, if I met the initial refusal to make an exception or interpret the rules creatively with polite sadness rather than anger, I would subsequently discover that the functionaries had done exactly what I wanted even after declaring it to be impossible; they were experts at identifying exceptions that ultimately validated the system of rules while allowing them to satisfy their clients’ needs. This pattern, I soon discovered, extended from relatively highly-placed officials to restaurant staff members. Other foreigners subsequently confirmed my impressions; some Dutch friends, perhaps bemused, nevertheless also largely agreed.

Despite such assurances, so sweeping a characterization of Dutch bureaucratic practices is unquestionably over-generalized. If that concern holds for a few sentences about one country, however, how much more it must apply to the Graeber’s far larger claim that bureaucracy is invariably stupid. Stupidity does not inhere in a system; it describes the alleged capacities of those who operate the system or the capacities they would like to produce in others (p. 95). To blame the stupid system is an almost proverbial excuse, in many cultural contexts, for failures of both bureaucrat and client. Adroit management of excuses may signal the exact opposite of stupidity.

Graeber’s image of bureaucracy is largely based on the American experience; he posits Madagascar contrastively as, for historical reasons, a place where bureaucracy has little impact on everyday life. But there are vast numbers of intermediate cases (as he recognizes, p. 22). While it is true that the American model threatens to dominate much of the world for reasons that Graeber ably lays out for us as he documents its seemingly inexorable, creeping expansion, it sometimes blinds us to the potentiality for pragmatic variation concealed within its systemic similarity. Hence the unresolved tension in Graeber’s text between the fine ethnographer-historian’s sensitivity to local detail and the political activist’s tendency to universalize local experience.

Some of the generalizations hold true for demonstrable historical reasons. Even then, however, the pandemic-like spread of bureaucratic practices – what Graeber (p.9) calls the Iron Law of Liberalism – is filtered through widely differing sociocultural expectations. Graeber’s Iron Law bears an uncanny (and unacknowledged) resemblance to “Parkinson’s Law” [Parkinson 1958], a similar elaboration of common knowledge; while Graeber may be right to argue (pp. 51-52) that anthropologists have been reluctant to tackle the boring paperwork aspects of bureaucracy, writers like Parkinson can perhaps be read as ethnographers if not as anthropologists in the strict sense. Yet the differences among bureaucratic systems are also important, even with regard to the paperwork (see Hull 2012). Anyone who has experienced the Chinese version of the academic audit culture, which superficially appears to follow the American model in its schematic numerology, quickly apprehends the huge difference in application and impact. Local actors play by local understandings of the rules, as Watson’s observations on globalization would lead us to expect.

In keeping with his critique of its reductionism and reliance on schematization, Graeber sees bureaucracy as the antithesis of imagination, which he identifies with revolution (pp. 92-93). This insight echoes the conventional understanding that bureaucracy often does repress imaginative practices. In reality, however, considerable inventiveness may go into bureaucratic management – something that Graeber repeatedly acknowledges, by showing how “interpretative labor” is carried out largely by the subaltern classes, including lower-level bureaucrats, since those with power feel no pressing need to interpret anything their supposed inferiors do. (The wealthy often don’t even bother to pay taxes; let the minions sort all that out – and, if fines are levied, they will only affect a tiny fraction of the offenders’ wealth.) It is not only the surveilled who must master interpretative techniques; those conducting the surveillance must do the same inasmuch as they will have to file reports with their superiors. This emphasis on the hierarchical positioning of bureaucrats accords with Graeber’s view – generously and convincingly attributed to feminist inspiration – of where interpretative labor occurs.

Ethnographic research on policing (e.g., Cabot 2018; Glaeser 1999; Haanstad 2013; Oberfield 2014) complicates – but does not entirely invalidate – Graeber’s generic intimations that police (whatever other goals they may pursue) rarely tackle crime directly (p. 73) and that bureaucracy precludes the exercise of intelligence. Graeber might have argued, reasonably enough, that it is not bureaucrats who are stupid but the bureaucracy. Eliding the actors into the abstract category, however, is a dangerous source of confusion – actually, in Graeber’s own terms, a bureaucratic one.

Graeber’s treatment of police is consistent with his anarchism. There can be no question but that in the American and British contexts it is, sadly, borne out by acts of racist and sexist brutality only recently acknowledged by the media and by the law. Here, however, we might ask whether the turning of the tide (if what we are seeing is more than a mere flash in the pan) parallels a potential recovery of technological mastery and inventiveness. If so, Graeber’s dystopian vision of a world increasingly dominated by a few ruthless, super-rich men, bent on thwarting scientific advances and socio-economic equality alike, might be an overstatement or, at least, a genuine insight into a situation that has nonetheless already begun to change. Agreed, evidence for a return to a more imaginative world is still remarkably thin. Graeber presumably entertained hopes, however, that the world might be re-enchanted, even, perhaps, acquiring a reconfigured and tamed bureaucracy (see p. 164). Only by means of such a conviction could he have sustained his passionate activism.

Here I am struck by the accuracy of the distinction he draws between his concept of imagination and Benedict Anderson’s (1991). While some contest his criticism of Anderson as too narrowly concerned with newspapers and nationalism, the difference is striking. Anderson’s use of imagination has more in common with the semiotic concept of iconicity (we imagine our co-nationals to resemble ourselves), whereas Graeber saw in imagination the recognition of radical difference and innovation. Here again, however, I worry that Graeber’s monochromatic portrayal of bureaucracy – its lack of cultural specificity – overlooks pre-existing and sometimes highly localized cultural predispositions as well as the presence of skilled and sympathetic actors.

Anthropology handed a poisoned chalice to the bureaucratic apparatus of the state in the nineteenth century: the concept of reified, bounded cultures. Historically, our discipline should be taking more responsibility than it has usually admitted for providing the instrument of ideologies that too easily morphed into racism and fascism. By talking about “the state,” Graeber skates around the deployment of the concept of national identity and the threat that this poses to the masses who get dragged into wars and humiliating labor conditions in the name of national redemption – a story that largely confirms his understanding of how capital works on the global stage. The ease with which the idea of the state gets fused with that of the nation-state has recently led me to express a preference for the intentionally clumsier term “bureaucratic ethnonational state” (Herzfeld 2022b). Ethno-nationalism is one of the dirtiest tricks perpetrated against the poor by a self-indulgent leadership. It both deploys local cultural features and is inflected by them; its appeal, framed as liberation, can reinforce local warlordism and global domination at the same time. Anthropological analysis threatens it precisely because it leads us back to the cultural specificities that give the global structures of power their local traction; it also shows that a unidirectional model of globalization is as facile as unidirectional models of social evolution (see, e.g., Tambiah 1989).

Graeber does display some affection for evolutionary conceptions of political life, as when he displays fascination with “heroic” histories. His historical vision of the heroic, however, has more in common with Vico than with Darwin; he does not see heroic societies as representing a single stage of past evolution. Rather, he seeks to recuperate from these exceptional historical moments the power of imagination, now divorced from aristocratic control, as an antidote to the numbing regularities of bureaucracy and as a path to the resuscitation of technological ingenuity.

Graeber describes vast areas of bureaucratic mismanagement with impressive, terrifying accuracy. He is at his best when he ethnographically describes the area of bureaucratic activity that he knows best, that of the academic world. Some other autobiographical moments are ethnographic gems in their own right, notably the sad account of his tussles with the health bureaucracy as his mother lay fatally stricken – a striking disproof of his contention (p. 52) that bureaucratic procedures cannot be subject to lively thick description. Moreover, no academic could seriously dispute his engaging account of how increasing amounts of scholars’ time, as well as that of doctors and other health professionals, are gobbled up by deadening, useless audits (Shore and Wright 1999; Strathern 2000).

Yet resistance remains possible. Graeber correctly observes that no matter what we write, the rest of the world barely even notices. We should nevertheless try to find a way to make the world care; the effective suppression of our calling stifles an important and useful commentary on the state of the world at large. If that were not the case, why would Graeber have written this book? Why would anyone not simply down tools and give up? (Of course, some have; but theirs is a dispiriting surrender to what I call “vicarious fatalism” – the apparently axiomatic ascription of passivity to the underdog by those with power in virtually every social inequality known to humankind.)

Resistance is not easy; some of the impediments are present in our own educational and cultural backgrounds. Graeber’s use of classical Greek (and more generally European) history, for example, hints at the difficulty that all Western anthropologists experience in standing back from their own assumed intellectual and cultural heritage, as well as the intellectual rewards of making that effort. Note, for example, his Vichian emphasis on etymological links between the ancient Greek polis and the modern word “police” and its cognates in multiple languages (not, however, including modern Greek, in which the police is astinomia, the controller of urban space; see also Cabot 2018). The Latin-derived terms “civility” and “civilization” hold similarly rich and ambiguous implications.

“Polite,” on the other hand, probably does not, pace Graeber, share the Greek derivation of “police,” but from a Latin word denoting “cleansing” (with sinister echoes of Mary Douglas’ [1966] perennially useful analysis of purity and pollution). It, too, has a richly ambiguous etymology. “Civility” suggests, as does the Italian use of the adjective civile (see Herzfeld 2009: 182) or even the English “civil society,” that sometimes being civil demands facing the police down when they overstep the boundaries of decency. The polity (classical Greek politeia) may not be a polis or a police state. It may represent an archaic structure pushed aside by violent modernity or it may be a completely novel one such as those imagined by intentional communities. But the possibility of resistance to the bureaucratic ethnonational state, with its police enforcement of conformity to repressive cultural norms, is essential to ensuring a bearable future and is the best way of ensuring civility.

The bureaucratization of morality is decidedly uncivil. An example of audit culture that constrains civility (not to speak of academic freedom!) appears in the bureaucratization of research ethics – a confusion of true ethics (Graeber’s scathing discussion of value-free ethics, pp. 166-67, is especially pertinent here!) with its simulation (a term Graeber usefully derives from Baudrillard and Eco). This perversion of ethics is especially painful for anthropologists because the very unpredictability of their research defies the scientistic logic of bureaucracy (“proposal design”). That logic also ignores the cultural specificity of ethics – an instance of what Graeber (p. 75) calls “ignoring all the subtleties of real social existence” – and now, through the imposition of rules backed by fear of legal consequences, bids fair, if we fail to resist, to make ethnography itself impossible. Occasional revolts against the centrality of ethnography because of past ethical errors risk collusion in perpetuating the injustices of the present, much as segments of the Left, in Graeber’s account (p. 6), have sometimes colluded in spreading the miasma of bureaucracy-speak and its oppressive effects. Intensified bureaucracy is no solution to ethnography’s ethical dilemmas. On the contrary, here as much as anywhere it conforms to Graeber’s striking insight (p. 103) that bureaucratic violence is less about making people talk than forcing them to shut up. Ethnographers, too, must resist being silenced by the avalanche of paperwork.

Ethnography, in fact, can expose abuses of power. It therefore poses a genuine threat to the powerful; ethics regulations not only protect universities from being sued but provide a potential shield for powerful bureaucrats should the anthropologists get too nosy. These authority figures also have resources of their own. A few hardy anthropologists have nevertheless pushed forward with pathbreaking ethnographic studies of dominant financial institutions. Among these, Douglas Holmes (2013), examining the management practices of central banks, offers a clear demonstration of why, as Graeber saw (p. 20), the bourgeoisie so passively obeys the financial bureaucracy. Such studies usefully complicate Graeber’s claim that the weak necessarily perform more interpretative labor than the powerful; they also pierce the iron shield of ethics, with its talk of confidentiality, transparency, and impartiality (otherwise, significantly, called indifference; see p. 184). Holmes, for example, examines the methods with which bank officials study the public – all of them virtual anthropologists, and with nary an ethics committee to restrain them.

Graeber’s book is in every sense a tour de force. I have focused this discussion on a set of interlocking points that strike me as particularly timely for the discipline and for the current state of the world. The book’s main provocation lies in Graeber’s critical reading of both the dominant economic system and the mass-produced and imitative critiques of it that sometimes pass muster as serious academic commentary (or at least satisfy audit-culture assessments for tenure and promotion). Its potential weaknesses lie in his avoidance of specificity where critics could easily find counter-factual examples in local contexts. Offsetting its occasional narrowness of cultural focus is the corrective that it offers to assumptions about universal value and globalization. A good ethnography is always more than simply a description of a local society. The Utopia of Rules is much more – and at times rather less – than an analysis of bureaucracy. It is a challenge still waiting to be taken up “in the field” – wherever that may be. It retains the potential to contradict its own pessimism and affect the trajectory of human society in the years, even decades, ahead.

Michael Herzfeld is Ernest E. Monrad Research Professor of the Social Sciences in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University and IIAS Professor of Critical Heritage Studies Emeritus at the University of Leiden, is the author of twelve books, most recently Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage, and also including Ours Once More: Folklore Ideology and The Making of Modern Greece and The Social Production of Indifference: Exploring the Symbolic Roots of Western Bureaucracy. He is currently working on a global study of crypto-colonialism.

This text was supposed to be presented at David Graeber LSE Tribute Seminar on “Bureaucracy”, but the seminar was canceled by the LSE faculty strike for better working conditions in academia.

References

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. Revised edition. London: Verso.

Cabot, Heath. 2018. The Good Police Officer: Ambivalent Intimacies with the State in the Greek Asylum Procedure.” In Kevin G. Karpial and William Garriott, eds. The Anthropology of Police (Abingdon: Routledge), pp. 210–29.

Douglas, Mary. 1966. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Glaeser, Andreas. 1990. Divided in Unity: Identity, Germany, and the Berlin Police. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Haanstad, Eric J. 2013. Thai Police in Refractive Cultural Practice. In William Garriott, ed., Policing and Contemporary Governance: The Anthropology of Police in Practice (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillian), pp. 181-205.

Herzfeld, Michael. 1992. The Social Production of Indifference: Exploring the Symbolic Roots of Western Bureaucracy. Oxford: Berg.

Herzfeld, Michael. 2009. Evicted from Eternity: The Restructuring of Modern Rome. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Herzfeld, Michael. 2016. 2016. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics and the Real Life of States, Societies, and Institutions. 3rd edition. New York: Routledge.

Herzfeld, Michael. 2022a. Pandemia, panico e paradossi della politica di salute pubblica. Atlante, Storie corali. https://www.treccani.it/magazine/atlante/societa/Storie_corali_Pandemia_panico.html

Herzfeld, Michael. 2022b. Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Hinton, Peter. 1992. “Meetings as Ritual: Thai Officials, Western Consultants and Development Planning in Northern Thailand.” Pp. 105–24 in Patterns and Illustrations: Thai Patterns of Thought, edited by Gehan Wijewewardene and E.C. Chapman. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Holmes, Douglas R. 2013. Economy of Words: Communicative Imperatives in Central Banks. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hull, Matthew. 2012. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. University ofCalifornia Press, Berkeley.

Little Walter E., and Cristiana Panella, ed. 2021. Norms and Illegality: Intimate Ethnographies and Politics. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Luhby, Tami. 2021. “As Millions Fell into Poverty during the Pandemic, Billionaires’ Wealth Soared. CNN Business. https://www.cnn.com/2021/12/07/business/global-wealth-income-gap/index.html

Oberfield, Zachary W. 2014. Becoming Bureaucrats: Socialization at the Front Lines of Government Service. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Parkinson, C. Northcote. 1958. Parkinson’s Law: The Pursuit of Progress. London: John Murray.

Schneider, Peter. 1969. Honor and Conflict in a Sicilian Town. Anthropological Quarterly 42: 130-54.

Shore, Cris, and Susan Wright. 1999. Audit Culture and Anthropology: The Rise of Neoliberalism in Higher Education. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 5:557–75.

Strathern, Marilyn, ed., 2000. Audit Culture: Anthropological Studies in Accountability, Ethics, and the Academy. London: Routledge.

Tambiah, Stanley J. 1989. Ethnic Conflict in the World Today. American Ethnologist 16:335–49.

Watson, James L. 2006. Introduction: Transnationalism, Localization, and Fast Foods in East Asia. In James L. Watson, ed., Golden Arches East: McDonald’s in East Asia, (2nd edition; Stanford: Stanford University Press), pp. 1-38.

Cite as: Herzfeld, Michael. 2022. “The Slyness of Stupidity: A Commentary on David Graeber’s The Utopia of Rules.” FocaalBlog, 9 February. https://www.focaalblog.com/2022/02/09/michael-herzfeld-the-slyness-of-stupidity-a-commentary-on-david-graebers-the-utopia-of-rules/

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.