David Graeber’s Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar began life as his University of Chicago doctoral thesis. It was not for some years that it appeared in print. That was 2007, and by then he had already published a considerable amount of other work, including a couple of significant books. To my shame, I have to admit that I hadn’t read Lost People until Alpa signed me up to comment on it today and that I should never have accepted her invitation. I am neither a specialist on Madagascar, nor expert in the literature on slavery or on narrative and history. But it’s worse than that. Something I have always especially admired about David’s writing is its clarity; his ability to state propositions that seem blindingly obvious once he has set them out but were never obvious before. Several of Lost People’s reviewers comment on its literary qualities, so I guess it’s just me. For my part, however, I found it uncharacteristically heavy-going, its narrative labyrinthine and its detail overwhelming. I was often unsure that I was getting the point.

David himself describes its style as experimental, “a kind of cross between an ethnography and a long Russian novel.” The aspiration was to produce a ‘dialogic ethnography’ that would do away with the distance between author and informants created – as David sees it – by so much social science writing. As I’ll later explain, he here draws a sharp distinction between social scientists and historians, and he identifies himself squarely with the latter. His sympathies are with what he represents as old-style ethnography where the objective is to provide a window on a way of life rather than to deploy ethnography – as is currently usual – as a prop for some single theoretical argument. He wants his Malagasy interlocutors to emerge “as both actors in history, and as historians” (Graeber 2007, 379).

Despite the difficulties of his text, it’s relatively easy to say what it’s centrally about and to summarise its main narrative. In case there are people present who haven’t read it, or whose memories need refreshing, that’s what I’ll do. It’s centrally about slavery, about its local history, and more especially about its post-abolition legacy. Above all, that is, it’s about the past in the present, about the ways in which history impinges on contemporary relations between people of free and of slave descent in a rural area in the western highlands of Madagascar, an hour or so drive from the capital, Antananarivo. Betafo (his fieldsite) is in Imerina, the old kingdom of the Merina people, who ruled most of the island in the nineteenth century, and of whom Maurice Bloch has written with such distinction. David’s main window on these relationships is through the narrative of an ordeal held in 1987, that provoked the ancestors, resulted in disaster for the principal protagonists, and ended by dividing the community even more deeply than formerly between people of slave descent and the “nobles” who had been their erstwhile masters. This narrative threads through the book with new interpretations, new perspectives on it, and new details piling up over 400 pages.

Betafo, something like a parish, is made up of around fifteen scattered hamlets which in total have a floating population of 300-500. It’s locally notorious for witchcraft and sorcery, and for the hostility of relations between its inhabitants – a major reason for selecting it, David reports. In the 1980s, it experienced an epidemic of petty thefts. The village assembly decided to hold an ordeal to identify the culprit(s). The villagers were to drink water in which earth from the ancestors’ tombs had been dissolved. But since they were not all of the same ancestry – there were nobles and ex-slaves, who were in principle totally separate groups between whom marriage was theoretically impossible – the earth should come from two separate tombs. And even that was a political fudge because the ex-slaves weren’t in fact a single descent group, though that is how the procedure adopted for the ordeal represented them. Nor was this provocative mixing of earth the only dangerous blunder. It turns out that both elders who had instigated and organised the ordeal – one noble, one slave – had recently taken a wife from the other group. They were guilty of mixing bodily fluids and bloods as well. No wonder disaster followed. The rice had just been harvested and was still in the fields. A flash flood swept it away. Actually, it later transpired that it was only the crops of the two elders that were completely destroyed. This was 1987. David started his research three years later and witnessed the aftermath. What had been intended to reassert communal solidarity had provoked a definitive rift. Now ‘blacks’ (slave descendants) were avoiding ‘white’ (‘noble’) parts of Betafo and were exploiting their reputations for magical powers and knowledge of local taboos to harass and constrain Betafo nobles who had moved to the capital but were now threatening to return and to resume their lands.

In parenthesis, it should perhaps be said that by standards elsewhere, the levels of antagonism seem muted. Returnee nobles might be told that there was a taboo on taking water from a particular spring. They weren’t physically attacked or forcibly prevented from moving back home. Intermarriage was anathematized, but we nevertheless hear of quite a few instances. None had resulted in murder, nor even in serious boycott. Compare rural Bihar or Haryana where couples who have contracted such serious misalliances could never be sure of their safety.

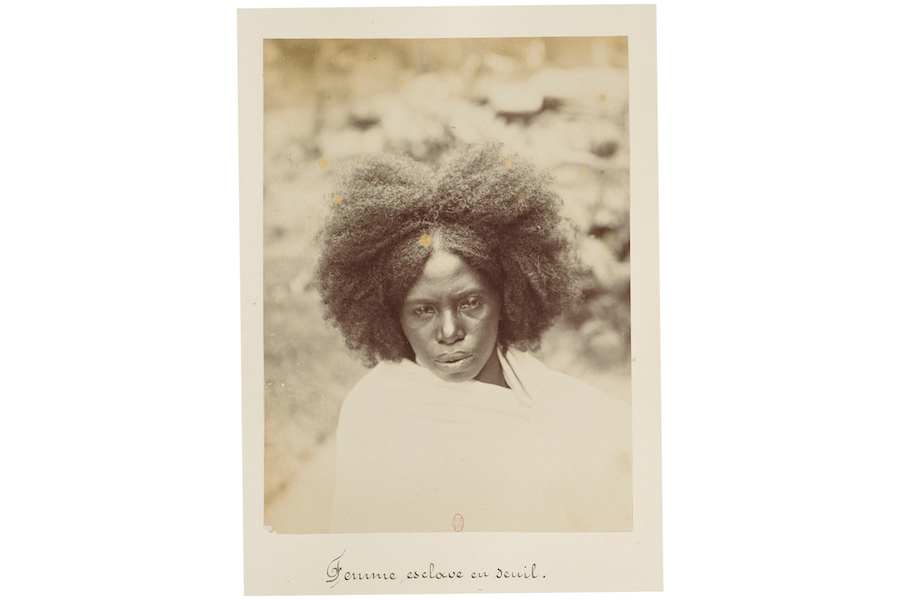

Even in eighteenth century Madagascar, slavery and slave-trading had a prominent role in many local economies. In the nineteenth, however, slavery took off spectacularly in Imerina after the British did a deal with the Merina king by which he agreed to halt the international trade of slaves for guns on the understanding that the British would supply him with guns anyway (and would not supply his rivals). That enabled the Merina state to dominate most of the island and to capture more and more slaves. They were deployed on public works and in agriculture in the Merina heartlands from where more and more Merina went as soldiers. Later in the century, perhaps as many as half Imerina’s population were slaves, according to Bloch. It was in any event an enormous proportion and that had a profound impact on Merina society and cultural representations.

The French annexed Madagascar in 1895. Slavery was abolished in 1897. From Betafo many nobles moved off to the capital to join the civil service, a few to Paris. Their former slaves became their sharecroppers and generally thrived. That was widely attributed to their manipulation of their magical powers. The downward mobility of many nobles was put down to the sins of slavery – even by nobles themselves. Nobles were increasingly deeply divided between a rich elite (who largely moved out) and the poor (who largely remained). David offers a vivid picture of just how opulent and aristocratic these rich nobles were in the early years of the colonial period with their twilit parties, music and dancing, and their colourful silk garments and golden diadems. Still at the time of his fieldwork, émigré nobles would descend on Betafo in numbers to collect a share of the harvest or to bury some kinsman in their ancestral tomb. When a corpse was flown in from Paris, the paths were jammed with cars and vans, and in their hundreds ‘everywhere around the tomb were knots of grave-looking men in three-piece suits with expensive watches, ladies in silk dresses, pearls, gold and silver jewellery.’ Within village society itself, however, the most fundamental division – regardless of class – remained that between andriana (nobles) and andevo (slaves). Though the topic of slavery was avoided, nobody could ever forget it, and slaves were still associated with pollution and ideas of contamination.

Crucially, however the situation of many of these émigré nobles became seriously precarious after the 1972 revolution. Subsequent to it, the peasant sector was badly neglected. The government took vast loans for development which it could not service, resulting in insolvency, dependence on the IMF, structural adjustment, the slashing of state budgets, the withdrawal of welfare and services from the countryside, a catastrophic collapse in living standards and widespread pauperization. The state largely withdrew from places like Betafo, leaving them as “temporary autonomous zones.” At the same time, many metropolitan civil servants were badly impoverished and were tempted to move back to their ancestral villages to resume the land that their ex-slave sharecroppers had been cultivating. And that, of course, is the essential background to the tensions that resulted from the Betafo ordeal at the heart of Lost People.

What that background significantly qualifies, as it seems to me, is David’s claim to represent his informants as both actors in history and as historians. Of course, they are the first in a limited sense, but as actors they are highly constrained and have little autonomy. By that I mean to suggest that the most important part of the story that explains why Betafo’s andriana and andevo are at each other’s throats takes place off-stage between the Malagasy state and the IMF in Antananarivo’s corridors of power. That is what really drives the story and that bit of it is pure Graeber. It has no part in his informants’ narratives, which are as it were epiphenomenal. They are a derivative discourse that is somehow beside the main point. As historians, they were severely limited by having no access to sources that would give them a proper handle on that crucial background. That’s a no doubt rather crude way of introducing a more general reservation about David’s preoccupation with narrative. Nobody could possibly doubt its importance for history and politics, but Lost People repeatedly seems to claim that that’s what history and politics are. I worry that that leaves an awful lot out. If history is “mainly about the circulation of stories,” what of all the ecological, epidemiological and demographic influences on our lives of which we are often unconscious. If political action “is action that is intended to be recorded or narrated or in some way represented to others afterwards,” what kind of action is all the effort that goes into ensuring that so many of the deeds and misdeeds of rulers are never recorded. Representations, discourses and narratives are unarguably important, but they should not in my view be allowed to occupy all the space in an anthropological analysis.

In a podcast discussion of David’s Debt book chaired by Gillian Tett sometime after his death, one contributor acutely observed that if there is any one value that informed his work it is freedom. That made me wonder how Lost People fits in. Though it says little about freedom explicitly, the ethnography overwhelmingly suggests its absence. This is a society that seems entirely unable to escape its past. In David’s other writings, there is usually some possibility of escape from oppression that is provided by other ideological alternatives. Here the past seems almost inescapably tyrannical. The Merina are condemned to continually renew the legacy of guilt and resentment that stems from the history of slavery. And whether or not David intended us to put the two things together, his ethnography shows that the burden of the past goes well beyond that. The Merina ancestors play a significant role in the lives of their descendants, and in Bloch’s writings their influence seems mostly benign. In Lost People they come over as much more threatening. They are always telling the living what they cannot do and they regularly attack them. That provokes the resentment and hostility of the living, which are dramatically expressed in the secondary burial when the ancestral remains are assaulted, their bones crunched up, their dust bound tightly in wrappings, and they are securely locked up in their tombs once more. History, it seems, is some kind of prison against the walls of which the living can only bang their heads. Marx had already summed it brilliantly: “The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

All that prompts a series of comparative questions that I think are important, but which David passes by – largely I suspect because they fall outside the narrative frame of his informants. Crucially, why – well after a century since manumission – are the Merina still so obsessed by slavery? Partly no doubt on account of its scale and its cruelty, but there must be more to it. Recent contributions to the regional literature have drawn attention to wide variations between Malagasy societies in the degree to which slave descent remains stigmatised, in the extent to which they appear haunted by its history and in whether they are willing to speak of it at all. Margaret Brown (2004), and Denis Regnier and Dominique Somda (2018, Regnier 2020), make brave stabs at specifying the conditions that might explain that variation (differences in social structure, resources, ethnic mixing and migration, and according to whether the slaves were Malagasy or of African origin), while Luke Freeman (2013) writes illuminatingly about the mandatory silence on the subject of his Betsileo informants and of how that re-entrenches the stigma of slavery by making it literally unspeakable.

Moving right across to the other side of the Indian Ocean, the legacy of slavery in Sri Lanka is dramatically different. According to Nira Wikramasinghe’s (2020) recent book, the collective memory of it has been all but entirely obliterated. True, it was never on the same scale and was abolished some decades earlier than in Madagascar, but on her analysis, on the Ceylon side, the comparison would have to include the way in which the creolization brought about by slavery seriously challenged doctrines of racial purity in the south, and the way in which the enslavement of Tamil Untouchables by high-caste Tamil Vellalars subverted later political projects of Tamil nationalism in the north. But questions of that comparative order are not part of David’s enquiry.

The broader terrain on which he does locate his study, my final observation, concerns rather the relationship between history and the social sciences. I confess I find his pitch a bit puzzling and am hoping that somebody might help me out. What he postulates is a broad contrast between the concerns of social science, which have primarily to do with patterns of regularity and predictability, and the concerns of history which deals with the irregular and unpredictable. It’s “the record of those actions which are not simply cyclical, repetitive, or inevitable.” Anthropology should align itself with history. That seems to be above all because it is “the very concern with science, laws, and regularities that has been responsible for creating the sense of distance I have been trying so hard to efface; it is, paradoxically enough, the desire to seem objective that has been largely responsible for creating the impression that the people we study are some exotic, alien, ultimately unknowable other.” Personally, I don’t believe any of that, but what interests me more is whether you will be able to tell me whether this disciplinary opposition has resonances in David’s other work. Or is it, as I suspect, an opportunistic answer to the requirement to justify and explain the literary style he adopted in writing this book? Certainly, Debt seems to be larded with “social science”-type propositions about repetitive, predictable patterns: slavery played a key role in the rise of markets everywhere; bullion currency predominates in periods of generalised violence; coinage, slavery, markets and the state go inexorably together. . . and so it goes on.

Jonathan Parry is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Anthropology at the LSE. He is the author of Classes of Labour: Work and Life in a Central Indian Steel Town and co-editor with Chris Hann of Industrial Labor on the Margins of Capitalism. Parry writes more broadly on the classic anthropological themes of caste, kinship, marriage, and exchange. Alongside Maurice Bloch, he has also co-edited two classic works in anthropology, Death and the Regeneration of Life and Money and the Morality of Exchange.

This text was presented at the David Graeber LSE Tribute Seminar on ‘Lost People’.

References

Brown, Margaret L. 2004. Reclaiming lost ancestors and acknowledging slave descent: insights from Madagascar. Comparative studies in society and history, 46(3), 616-645.

Freeman, Luke. 2013. Speech, silence, and slave descent in highland Madagascar. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 19(3), 600-617.

Graeber, David. 2007. Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

———. 2011. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

Regnier, Denis. (2020). Slavery and Essentialism in Highland Madagascar: Ethnography, History, Cognition. New York: Routledge.

Regnier, Denis, and Somda, Dominique. (2019). Slavery and post-slavery in Madagascar: An overview. In T. Falola, D., R. J. Parrott & D. Porter Sanchez (eds.), African Islands: Leading Edges of Empire and Globalization. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. Pp. 345-369.

Wickramasinghe, Nira. (2020). Slave in a Palanquin. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cite as: Parry, Jonathan. 2021. “The Burdens of the Past: Comments on David Graeber’s Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar.” FocaalBlog, 7 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2021/12/07/jonathan-parry-the-burdens-of-the-past-comments-on-david-graebers-lost-people-magic-and-the-legacy-of-slavery-in-madagascar/

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.