In 2021 a modest long-haired Sakha man named Alexander Gabyshev was arrested at his family compound on the outskirts of Yakutsk in an unprecedented for Sakha Republic (Yakutia) show-of-force featuring nine police cars and over 50 police. For the third time in two years, he was subjected to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Some analysts see this medicalized punishment, increasingly common in President Putin’s 4th term, as a return to the politicized use of clinics that had been prevalent against dissidents in the Soviet period. Alexander’s hair was cut, and his dignity demeaned. By April, his health had seriously deteriorated, allegedly through use of debilitating drugs, and his sister feared for his life. A private video of his arrest (possibly filmed by a sympathetic Sakha policeman) shows police overwhelming him in bed as if they were expecting a wild animal; he was forced to the floor bleeding, and handcuffed. Official media claimed he had resisted arrest using a traditional Sakha knife, but this is not evident on the video. By May, a trial in Yakutsk affirmed the legality of his arrest, and a further criminal case was brought against him using the Russian criminal code article 280 against extremism. Appeals are pending, including one accepted by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

What had elicited such official vehemence against an opposition figure who had dared to critique President Putin but whose powers and influence were relatively minor, compared to prominent Russians like Aleksei Naval’ny? How did a localized movement in far-from-Moscow Siberia become well-known across Russia and beyond?

In his 2018–2019 meteoric rise to national and international attention, Alexander Prokopievich Gabyshev, also called “Shaman Alexander,” “Sasha shaman,” and “Sania,” came to mean many things to many people. For some, he is a potent symbol of protest against a corrupt regime led by a president he calls “a demon.” For others, he has become a coopted tool in some part of the government’s diabolical security system, set to attract followers so that they can be exposed and repressed. Some feel he is a “brave fellow” (molodets), “speaking truth to power” in a refreshingly articulate voice devoid of egotism. Others see him as misguided and psychologically unstable, made “crazy” by a tragic life that includes the death of his beloved wife before they could have children. Some accept him into the Sakha shamanic tradition, arguing his suffering and two–three years spent in the taiga after his wife’s death qualify him as a leader and healer who endured “spirit torture” in order to serve others. Others, including some Sakha and Buryat shamans, reject him as a charlatan whose education as an historian was wasted when he became a welder, street cleaner, and plumber.

These and many other interpretations are debated by my Russian and non-Russian friends with a passion that at minimum reveals he has touched a nerve in Russia’s body politic. It is worth describing how Alexander, born in 1968, describes himself and his mission as a “warrior shaman” before analyzing his significance and his peril.

Alexander’s Movement

Picture Alexander on foot pushing a gurney and surrounded by well-wishers, walking a mountainous highway before being arrested by masked armed police for “extremism” in September 2019. Among over a hundred internet video clips of Alexander’s epic journey from Yakutsk to Ulan-Ude via Chita, is an interview from Shaman on the Move! (June 12, 2019):

I asked, beseeched God, to give me witness and insight….I went into the taiga [after my wife had died of a dreadful disease ten years ago]….It is hard for a Yakut [Sakha person] to live off the land, not regularly eating meat and fish….I came out of the forest a warrior shaman….To the people of Russia, I say “choose for yourself a normal leader,… young, competent”….To the leaders of the regions, I say “take care of your local people and the issues they care about and give them freedom.”…To the people, I say “don’t be afraid of that freedom.” We are endlessly paying, paying out….Will our resources last for our grandchildren? Not at the rate we are going… Give simple people bank credit.. . Let everyone have free education and the chance to choose their careers freely.. . There should not be prisons….But we in Russia [rossiiane] have not achieved this yet, far from it…Our prisons are terrifying….At least make the prisons humane…. For our small businesses, let them flourish before taking taxes from them. Just take taxes from the big, rich businesses….For our agriculture, do not take taxes from people with only a few cows….Take from only the big agro-business enterprises.[1]

In this interview and others, Alexander made clear he is patriotic, a citizen of Russia, who wants to purify its leadership. “Let the world want to be like us in Russia,” he proclaimed, “We need young, free, open leadership.” While he explains that “for a shaman, authority is anathema,” he has praised the relatively young and dynamic head of Sakha Republic: “Aisen [Nikolaev] is a simple person at heart who wants to defend his people, but he is constrained, under the fear of the demon in power [in the Kremlin].” Alexander acknowledges the route he has chosen is difficult, and that many will try to stop him. Indeed he began his “march to Moscow” three separate times, once in 2018 and twice in 2019, including after his arrest when he temporarily slipped away from house arrest in December 2019, was rearrested and fined.

Alexander’s 2021 arrest, described in the opening paragraph, was hastened by his refusal to cooperate with medical personnel as a psychiatric outpatient, and further provoked when he announced he would once again try to reach Moscow, this time on a white horse with a caravan of followers. His video announcement of the new plans, with a photo of him galloping on his white horse carrying an old Sakha warrior’s standard, mentioned that he would begin his Spring renewal journey by visiting the sacred lands of his ancestors in the Viliui (Suntar) territories, “source of my strength.” He encouraged followers to join him, since “truth is with us.”[2] A multiethnic group of followers launched plans to gather sympathizers in a marathon car, van and bus motorcade. Their route was designated to pass through the sacred Altai Mountains region of Southern Siberia. What had begun as a quirky political action on foot acquired the character of a media-savvy pilgrimage.

At moments of peak rhetoric, Alexander often explained that “for freedom you need to struggle.” Into 2021, he hoped to achieve his goal of reaching Red Square to perform his “exorcism ritual.” But his arrests and re-confinement in a psychiatric clinic under punishing “close observation” conditions make that increasingly unlikely, especially given massive crackdowns on all of President Putin’s opponents, including Aleksei Naval’ny and his many supporters. One of Alexander’s most telling early barbs critiqued the “political intelligentsia,” who hold “too many meetings” and do not accomplish enough. He told them: “It is time to stop deceiving us.” Yet he repeated in many interviews that numerous politicians in Russia, across the political spectrum, would be better alternatives than the current occupant of the Kremlin.

Among Alexander’s most controversial actions before he was arrested was a rally and ritual held in Chita in July 2019, on a microphone-equipped stage under the banner “Return the Town and Country to the People.” After watching the soft-spoken and articulate Alexander on the internet for months, I was amazed to see him adopt a more crowd-rousing style, asking hundreds of diverse multiethnic demonstrators to chant, “That is the law” (Eto zakon!) even before he told them what they would be answering in a “call and response” exchange. He bellowed, “give us self-determination,” and the crowd answered, “That is the law.” He cried, “give us freedom to choose our local administrations,” and the crowd answered, “That is the law.” His finale included “Putin has no control over you! Live free!” Only after this rally did I begin to wonder who, if anyone, was coaching him and why. Had he changed in the process of walking, gaining loyal followers, and talking to myriad media? The rally, with crowd estimates from seven hundred to one thousand, had been organized by the local Communist Party opposition. Local Russian Orthodox authorities denounced it and suggested that Alexander was psychologically unwell. Alexander himself simply said, after his arrest, “It is impossible to sit home when a demon is in the Kremlin.”

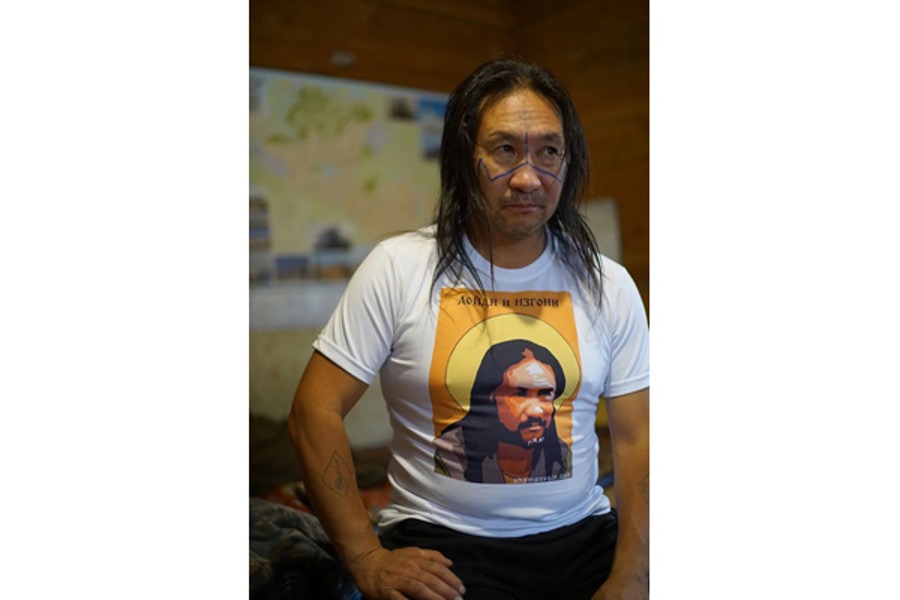

How and why was Alexander using discourses of demonology? He seemed to be articulating Russian and Sakha beliefs in a society that can be undermined by evil out of control. When he first emerged from the forest, he built a small chapel-memorial in honor of his beloved wife and talked in rhetoric that made connections as much to Russian Orthodoxy as to shamanic tradition. He wore eclectic t-shirts, including one that referenced Cuba and another the petroglyph horse-and-rider seal of the Sakha Republic. Once he began his trek, he wore a particularly striking t-shirt eventually mass-produced for his followers. Called “Arrive and Exorcise,” it was made for him by the Novosibirsk artist Konstantin Eremenko and rendered his face onto an icon-like halo.

Another popular image depicts Alexander as an angel with wings. He has called himself a “Holy Fool,” correlating his brazen actions and protest ideology directly to a Russian iurodivy tradition that enabled poor, dirty, beggar-like tricksters to speak disrespectful truths to tsars. His appeals to God were ambiguous—purposely referencing the God of Orthodoxy and the Sky Gods of the Turkic Heavens (Tengri) in his speeches. During his trek, and in some of his interviews, he has had paint on his face, a thunderbolt zigzag under his eyes and across the bridge of his nose that he calls a “sign of lightning,” derived from his spiritual awakening after meditation in the forest. He has claimed, as a “warrior shaman,” that he is fated to harness spirit power to heal social ills. While his emphasis has been on social ills that begin with the top leadership, he also has been willing to pray and place healing hands on the head of a Buryat woman complaining of chronic headaches, who afterwards joyously pronounced herself cured.

During his trek, on camera and off at evening campsites, Alexander fed the fire spirit pure white milk products, especially kumys (fermented mare’s milk), while offering prayers in the Sakha “white shaman” tradition that he hoped to bring to Red Square for a benevolent ritual not only of exorcism but of forgiveness and blessing. He chanted: “Go, Go, Vladimir Vladimirovich [Putin]. Go of your own free will . . . Only God can judge you. Urui Aikhal!” He expressed pride that some of the Sakha female shamans and elders have blessed his endeavor.

Resonance and Danger

Russian observers, including well-known politicians and eclectic citizens commenting online or on camera, have had wildly divergent reactions to Alexander, sometimes laughing and mocking his naïve, provincial, or perceived weirdo (chudak) persona. But some take him seriously, including the opposition politician Leonid Gozman, President of the All-Russia movement Union of Just Forces. Leonid, admiring Alexander’s bravery, sees significance in how many supporters fed and sheltered him along his nearly two-thousand-kilometer trek before he was arrested. Rather than resenting him for insulting Russia’s wealthy and powerful president, whose survey ratings have plummeted, Alexander’s followers rallied and protected him with a base broader than many opposition politicians have been able to pull together.

As elsewhere in Russia, civic society mobilizers, whether for ecology protests, anti-corruption campaigns or other causes, are becoming savvy at hiding and sharing leadership. By 2021, Alexander had become one of many imprisoned oppositionists, whose numbers throughout Russia have swelled beyond the prisoners of conscience documented when the great physicist Andrei Sakharov was exiled to Gorky in 1985.[3]

Alexander, despite being subdued beyond recognition after multiple arrests, has affirmed that he was hoping for “neither chaos nor revolution, [since] this is the twenty-first century.” He advocates for his followers an “open world, [of ] peace, freedom and solidarity,” one where all people believing in benevolent “higher forces” can find them. His significance is that he is one of the credible politicized spiritual leaders to emerge from Russia in the post-Soviet period, when in the past twenty years the costs of independent leadership have become increasingly dire, self-sacrifice is increasingly necessary, and multi-leveled community building with horizontal interconnections is increasingly risky.

Whether or not defined as religious or shamanic, the bravery and force of individuals willing to risk everything to change social conditions is awesome, transcending and human wherever we find it. Far from insane, these maverick societal shape-changers, tricksters and healers may represent our best power-diversifying hopes against systems that pull in directions of authoritarian repression. Perhaps once-populist power consolidating leaders like Vladimir Putin, who warily watch their public opinion ratings, are insecure enough to understand the deep systemic weaknesses that oppositionists like Alexander Gabyshev and Alexei Naval’ny expose, using very different styles along a sacred-secular continuum. President Putin’s insecurities magnify the importance of all political opposition, creating vortexes of violence and dangers of martyrdom in the name of stability.

Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer is a Faculty Fellow in the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs at Georgetown University. At Georgetown since 1987, she is co-founder of the Indigenous Studies Working Group https://indigeneity.georgetown.edu and has taught as Research Professor in the School of Foreign Service and anthropology departments. She is editor of the Taylor and Francis translation journal Anthropology and Archeology of Eurasia and is author or editor of six books on Russia and Siberia, including Galvanizing Nostalgia: Indigeneity and Sovereignty in Siberia (Cornell University Press, 2021).

Notes

[1] Many Alexander videos have disappeared from the internet, and others are private access. The series “Shaman idet!” [Shaman on the Move], and “Put’ shamana,” [Shaman’s Path] are especially relevant, e.g., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1jE71TAqZw, July 22, 2019 (accessed 6/18/2021). Shaman idet! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zPrb_1nWXtE, June 12, 2019 was accessed when released and 3/19/2020. See also “Shaman protiv Putin” [Shaman vs. Putin], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tfTEtiqDf6U, June 24, 2019 (accessed 7/3/2019); “Pochemu Kremlin ob”iavil voinu Shamanu—Grazhdanskaia oborona” [Why Did the Kremlin Fight the Shaman- Civil Defense] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7OVy2ROASQ (accessed 3/15/2020); and Oleg Boldyrev’s BBC interview September 24, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U0LaLhkKj2g (accessed 3/15/2020).

[2] Alexander described plans for the aborted 2021 journey: youtube.com/watch?v=YK0LlFAjx3E (accessed 1/15/2021). See also https://meduza.io/en/news/2021/01/12/yakut-shaman-alexander-gabyshev-announces-new-cross-country-campaign-on-horseback (accessed 6/4/2021).

[3] This Soviet and post-Soviet imprisonment comparison comes from brave opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza, himself poisoned twice, in a human rights review for the Kennan Institute, Woodrow Wilson Center, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/heightened-political-repression-russia-conversation-vladimir-kara-murza (accessed 6/18/2021).

Cite as: Balzer, Marjorie Mandelstam. 2021. “Siberia, Protest and Politics: Shaman Alexander in Danger.” FocaalBlog, 21 June. https://www.focaalblog.com/2021/06/21/marjorie-mandelstam-balzer-siberia-protest-and-politics-shaman-alexander-in-danger/.