This post is part of a feature on “Debating the EASA/PreAnthro Precarity Report,” moderated and edited by Stefan Voicu (CEU) and Don Kalb (University of Bergen).

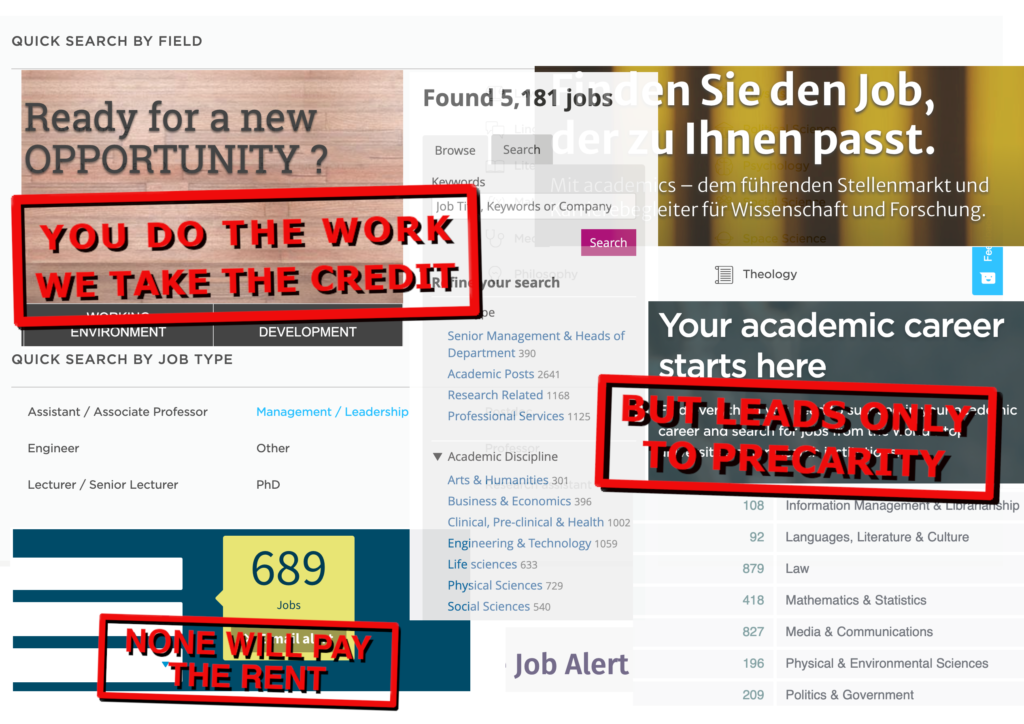

Every day across Europe hundreds of social anthropologists wake up knowing that their precarious employment conditions may one day force them to leave the discipline. Still, they keep the discipline going across the continent by teaching, providing vital research data for high-profile research projects and a substantial share of the annual publication output. They also apply for grants and jobs while balancing the tightrope of overtime work and personal life. All for the glimmer of hope of a permanent position.

If this has been going on for more than two decades now, the dire situation of many key workers (yes, key workers) in social anthropology does finally receive the attention it deserves. This is thanks to the work of the PrecAnthro Collective. Following interventions at the European Association of Social Anthropology (EASA) biannual conferences throughout the latter half of the 2010s, this collective of precarious anthropologists initiated and conducted research into precarity in European social anthropology under the umbrella of EASA.

Their report on The Anthropological Career in Europe (Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes 2020) presents statistical data that compares the difficulty to obtain a tenured position in social anthropology. As expected, it shows that class, gender, ethnicity, and nationality determine income and career opportunities. At the same time, the survey shows that most anthropologists seem willing to pursue such careers and often accept precarity as a condition for further advancement.

The report emerges in a wider context of upheaval in the discipline. Despite strike waves across some European nations (the UK in particular), most higher education trade unions keep a low profile on precarity. The scandal around the journal HAU, which we have featured in detail on FocaalBlog (Kalb 2018, Murphy 2018, Neveling 2018), remains unresolved to substantial extent. Our discipline has not recovered from that shock, as heated debates at the 2020 online bi-annual conference of EASA evidenced. Now, the push towards digitalization of teaching adds to an emerging outsourcing campaign under the Covid-19 pandemic. Already existing casualization of higher academic jobs engendered by the past decades of neoliberal reforms will most likely worsen (Ivancheva 2020).

This theme section sets out to support and deepen the debate and political campaign opened by PrecAnthro and their report for EASA. It gathers reflections, critiques, and extensions on the ‘precarity report’ from European anthropologists at different stages of their careers and from various tiers of the academic hierarchy.

What emerges from these interventions are two key tensions defining the anthropological career in Europe. First, there is the tension between the European and national academic institutional frameworks. As Giacomo Loperfido points out, there is a “Champions League” of academia, where, based on their ability to secure big grants, senior scholars can choose their place of employment and salary bracket in a structurally similar way as superstar football players. Simultaneously, the system breeds the precarious scholars employed on these big grants. These scholars have played an important role in the constitution of PrecAnthro and in some sense, the report, as Don Kalb notices in his contribution, can be read as a description of the precarity experienced by these highly mobile young researchers, embedded in international networks, trained to publish in English and able to satisfy the productivity standards of grant committees.

One the other hand, there are ‘national leagues’, with logics that differ from a EU academic labor market internationalism. Both Natalia Buier and Susana Narotzky emphasize the existence of precarious Spanish anthropologists whose different career trajectory-taylored for the local academic setting-as well as language and financial barriers limit or foreclose access to the EU academic labor market. Susana Narotzky argues that those international and national precarious scholars are pitted against each other as they compete for tenured positions. Arguing in a similar direction, Don Kalb suggests that in this competition those with locally embedded careers focused on teaching end up with tenure, while those with international research careers become expendable.

The second tension evident in the feature contributions is one inherent to the hierarchy of the academic system. As Ela Drazkiewicz points out, the academic system works like a Ponzi scheme. Senior scholars profit from the recruitment of junior scholars who can teach and do research for them, but they may also have to perform what Prem Kumar Rajaram calls ‘the more mundane care work’. Some are attracted by the false promise of a stable and respectable job, and, although the PrecAnthro report raises concerns about the exclusion of scholars with a working-class background, Natalia Buier suggests that this false promise might in fact contribute to the integration of those with a working-class background into the system. These precarious scholars thus perform key tasks that free up workload in senior scholars’ schedule so they can pursue more prestigious activities. And prestige, as both Ela Drazkiewicz and Prem Kumar Rajaram argue, is essential to the current functioning of the system. Reputation can indeed make or break an academic career and, as Ela Drazkiewicz tells us, the fear of having a bad reputation engenders a culture of silence and compliance.

The texts are arranged in a sequence that follows these tensions and pairs a junior scholar with a senior one. Don Kalb’s text outlines the broad political economic context in which the report emerges, going beyond the discipline itself, and is followed by Natalia Buier’s detailed scrutiny of the report’s findings. The blogs by Giacomo Loperfido and Susana Narotzky pair a PrecAnthro Collective member’s analysis how large international and EU grants generate precarity with the position of a former Principal Investigator on such projects. Finally, Ela Drazkiewicz reflects on her own career trajectory, whereas Prem Kumar Rajaram highlights the uneven relations between precarity, power, prestige, and unionization.

Bibliography

Fotta, Martin, Mariya Ivancheva and Raluca Pernes. 2020. The anthropological career in Europe: A complete report on the EASA membership survey. European Association of Social Anthropologists. https://easaonline.org/publications/precarityrep.

Iancheva, Mariya. 2020. “The casualization, digitalization, and outsourcing of academic labour: a wake-up call for trade unions.” http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/03/20/mariya-ivancheva-the-casualization-digitalization-and-outsourcing-of-academic-labour-a-wake-up-call-for-trade-unions/.

Kalb, Don. 2018. “HAU not: For David Graeber and the anthropological precariate.” www.focaalblog.com/2018/06/26/don-kalb-hau-not-for-david-graeber-and-the-anthropological-precariate.

Murphy, Fiona. 2018. “When gadflies become horses: On the unlikelihood of ethical critique from the academy.” www.focaalblog.com/2018/06/28/fiona-murphy-when-gadflies-become-horses.

Neveling, Patrick. 2018. “HAU and the latest stage of capitalism.” www.focaalblog.com/2018/06/22/patrick-neveling-hau-and-the-latest-stage-of-capitalism.

Cite as: Voicu, Stefan. 2021. “EASA’s ‘Precarity Report’: Reflections, Critiques, Extensions.” FocaalBlog, 27 January. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/01/27/introduction-stefan-voicu-easas-precarity-report-reflections-critiques-extensions

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.