Ramesh Sunam, Waseda University, Tokyo

Suraj (name changed), arrived a year ago from Nepal to study at a Japanese language institute in Nagoya, Japan. He was working part-time at a convenient shop to make a living. Unfortunately, Suraj’s situation has changed in the last two months following the outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19). In March, he faced a reduction in his working hours by 30 percent. At the outset of this month, his employer asked him to stay home until they call him back for work. Apparently, he lost his job, at least temporarily, through no fault of his own. When I spoke to him, he seemed deeply worried about his annual tuition fees of some US$ 8,000 due soon as well as about covering his living expenses. He cannot source the tuition fees from his own family living in Nepal because his family is already in debt due to the loan taken out for funding his journey to Japan. It cost him about US$ 13,000 to enter Japan on a student visa. During 16-18 hours days filled with studies and work, he struggled hard to make a living and pay tuition fees and to send money home to repay his travel and visa debt. The unexpected crisis has added another layer of vulnerability to his struggles. Since he has made lots of sacrifices to study in Japan, he is not in a position to go back home without completing studies and saving enough from precarious labor to repay his debts. He is also well aware about the situation in his own country, which is relatively unprepared for testing and treating COVID-19 cases.

Hailing from Vietnam, Huong has been in Japan for some five years. She works in a shopping mall in Tokyo as a salesperson. Unsurprisingly, the number of her working days has recently been shortened from five to three. Like Suraj, she worries about her survival in one of the most expensive global cities. The story of her migration to Japan is no less telling. She initially studied at a Japanese language institute, like Suraj, and then at a professional training/vocational college (senmon gakko), spending four years in total. However, her studies did not lead to a smooth landing in her current job. Instead, she had to go through a tedious visa application process. After taking recourse to an employment/staffing (Haken company), her third application granted her a one-year work visa in November last year. This process cost her about US$4,000. The visa processing took four months during which she was not legally entitled to take up any employment in Japan. In that period, she relied on generous friends and sometimes took a cash-in-hand job in housekeeping.

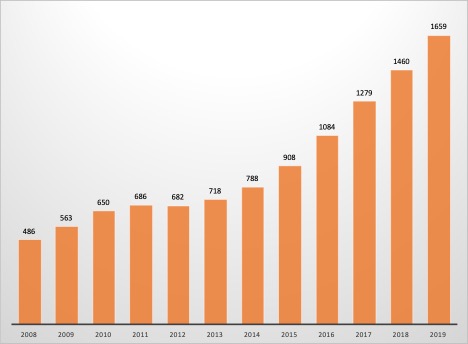

Suraj and Huong are no exceptions. There are many international students and migrant workers in Japan facing similar dire circumstances. In fact, their prospects may deteriorate further after the declaration of a state of emergency by the Japanese government in recent days. Japan hosts around 300,000 international students. More than half of them study at Japanese language institutes and professional training colleges. Most international students in Japan come from China, Vietnam, Nepal and the Republic of Korea. As of October 2019, Japan hosted 1.66 million ‘foreign workers’, mostly from China, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Engaged in physically demanding, elementary jobs in the labour-intensive sectors such as the manufacturing and retail sectors, many migrant workers are employed under precarious terms and conditions, including short-term contracts, job insecurity and long hours. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the most vulnerable appear to be those employed as outsourced workers (haken sha-in) in retail and in hospitality sectors, whereas permanent employees (sei-sha-in) are in a much better position. Based on my own research foreign workers, and among them international students, are already hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic and its economic fallout.

When I asked what would help them most, both Suraj and Huong said they would like to receive immediate cash support to tread water in these difficult times. At the same time, they also had specific pleas; Suraj wishes to have his tuition fees reduced and the due date for payment deferred, whereas Huong wants to see her visa automatically extended for another year so that she does not have to go through the same torturous and expensive process again this year.

It is yet to be seen whether the Japanese government turns a deaf ear to or addresses the concerns of precarious migrant workers like Suraj and Huong who contribute significantly to the Japanese economy. But one thing is hard to deny; how the Japanese government treats the existing foreign workers during this difficult time will determine the success or failure of its much-lauded, new immigration regime launched last year to address acute labour shortages amidst a rapidly ageing national population and a steadily falling birth-rate. Marking a bold policy shift from Japan’s earlier strict immigration rules, the new immigration scheme is designed to bring in up to 345,000 additional foreign workers over five years.

Yet, so far the new scheme has fallen worryingly short of that target, as it attracted only some 2,000 workers, about 5 percent of the 40,000 workers target set for the last fiscal year. Now, the Covid-19 outbreak has already slowed down the recruitment process of migrant workers, partly due to delays in the administration of language and skill tests in the migrant-sending countries. Given that the competition for migrant (‘foreign’) labor within Asia is increasing due to the pandemic, it will become more challenging for Japan to bring in additional migrant workers from across Asia. In light of current developments, prospective migrant workers may well (re)consider their choice of Japan as a future employment destination depending on how the Japanese government supports existing migrant workers now.

Thus, one remarkable development of the COVID-19 pandemic may be that migrant workers move from beggars to choosers. While the Japanese government is in serious discussions over emergency stimulus packages to support ‘struggling’ Japanese families and businesses, the fear looms large that foreign students and workers may be forgotten. Yet, for this labour-hungry country, immediate support for foreign workers and students in these critical times may be of long-term benefit. For now is perhaps the best opportunity for Japan to win the hearts of foreign students and workers as well as those of the global community.

Dr. Sunam is an Assistant Professor at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan. His current research focuses on intra-Asian labour migration, precarity and rural livelihoods. His new book ‘The Remittance Village: Transnational Labour Migration, Livelihoods and Agrarian Change in Nepal’ is forthcoming with Routledge, London. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the official position of his employer.

Cite as: Sunam, Ramesh. 2020. “The Precariousness of Migrant Workers in Japan amidst COVID-19.” FocaalBlog, 14 April. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/04/14/ramesh-sunam-the-precariousness-of-migrant-workers-in-japan-amidst-covid-19/

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.