At the end of February, the center of Italian capital encountered an unexpected problem. Not an unforeseeable one, but one that was not previously thought possible in the highly integrated European tertiary hub of Lombardy. Some weeks of contradictory official announcements passed by. Local and central governments, experts, and politicians first closed the few institutions that remained under public control after several years of privatization of public services, such as schools and libraries, and then came up with city marketing campaigns such as #MilanoNonSiFerma or #BergamoNonSiFerma (Milan/Bergamo doesn’t stop) intended to push everyone to keep the service sector and the productive economy up and running. Finally, at the end of the first week of March, the government frantically urged everyone in Italy to enact so-called social distancing and isolation at home.

To be clear, the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a real public health threat. At the time of writing, Italy counts more than 10,000 deaths caused by that virus in a single month, heading towards the 15,000 mark. Most infections and death occurred in Italy’s five Northern regions; with the country divided into twenty in total. This blog post has no intention to criticize the containment and delay measures taken. I neither have the instruments to evaluate them nor would such an evaluation be relevant to my argument. What I can do, though, is to assess what this crisis reveals about the present socio-historical conjuncture.

In response to the pandemic, Italian anthropologists soon opened up spaces to discuss the wide ranging aspects of the conflagration that shattered the complex normality in the peninsula. I strongly encourage anthropologists from other nations to look at this rich early discussion and the many links provided, as this broadens our view and puts in practice suggestions to include anthropological traditions overlooked in mainstream debates. That said, I remained paralyzed by a deluge of articles from other disciplines, dubious graphs, opaque numbers, and finally shocked inaction, which became overwhelming. So, I am afraid it is more from non-anthropologists, than from the rich discussions in the Italian anthropological community that my reflections are drawn.

Nonetheless, I would like to consider two concepts that emerged from these reflections—liminality (Turner 1967) and suspension (Remotti 2011)—since they may help us tackle the current extraordinary moment of collective confinement. We can use such notions as means through which to think systemically and reflexively about the current situation. I would also like to consider another near-forgotten classic anthropological term—the Taboo: that which is forbidden and cannot be touched, looked at, mentioned, or even recognized.

March 2020 was the month in which everyone in Italy woke up in the dystopia we were already in, without really knowing it. The profound and somewhat abstract social disconnection that only some people had been experiencing in the form of individualized and medicalized alienation, suddenly broadened to include everyone. In We’re Still Here (2019), sociologist Jennifer Silva dives into the fragmented pain of her informants, who had already been suffering from isolation and over medication. At the time of her research, just before Trump’s election, her informants remained in denial of the structural forces that shaped their abjection. I am not convinced that the concept of suffering provides access some kind of universal human essence. However, that notion may nonetheless help orient analysis towards the structuring of social conditions. This is precisely what Silva was aiming at. It seems to me that one of the first things that generalized confinement in the richest and most economically vibrant part of Italy (and among the wealthiest in Europe) shows is exactly what lies concealed: alienation and isolation.

These suggestions are not an excuse to lazily apply vague ideas of biopolitics, necropolitics, and the neoliberal self to the whole social sphere. It would be too easy (and inaccurate) to simply say that the current crisis is due to the creation of public panic by a state that always aims to mold and organize the bodies it wants to govern, as two immediately criticized articles by philosopher Giorgio Agamben seemed to suggest. The reality of the situation is much more complex. It is notable, however, that the first regulatory tactics used to contain the epidemic were isolation and social distancing, as if these were unproblematic and easily thinkable solutions. These alienating measures were suddenly available to deploy, and they have a striking continuity with the everyday experiences of many people prior to the pandemic. This is not to critique their biomedical efficacy. Yet, it leads us to question what was not thinkable, what was indeed problematic, what was not sayable; or at least what was not thinkable, indeed problematic, and not sayable before and in the first weeks of the outbreak.

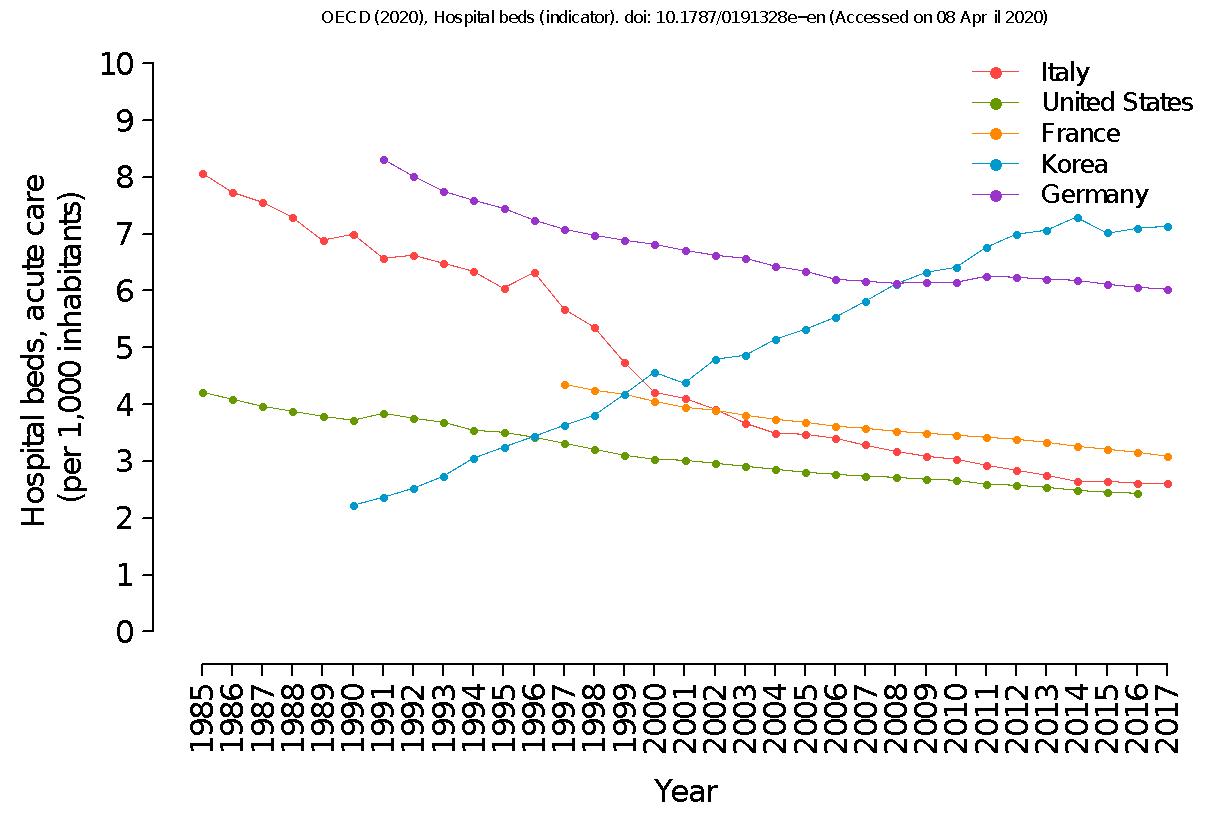

It was only during the mass slaughter of the virus that certain issues could be raised in mainstream public discussions. These were issues like the regionalization of public health care, which in Italy since the mid-90s has made every region autonomous in terms of healthcare; the neoliberal re-organization of health care in the name of local autonomy, flexibility, rationalization and so on; and the 37€ billion of annual de-funding since the 2008 great recession, which caused a near-collapse of Italy’s public health care system before the epidemic. The issues also include production—a topic that seemed to have disappeared in the post-crisis reform of the European Union. Production suddenly returned in daily conversations when it emerged that Italy (and actually most European countries) did not produce face masks or scrubs anymore, having for many years preferred buying them through now inaccessible international production chains.

Another unsayable topic of even higher importance to me is the collective and bizarrely obsessive focus on people walking on deserted streets, which began to spread on social media, in common conversations, and especially in television broadcasts. In the first days of (the quite extraordinary adherence to) quarantine measures, those who were walking were portrayed as moral culprits of the contagion. The perceived danger of those (mostly) imaginary enemies of public health increased so much that authorities arrived at the point of using firefighters, the police, and the army to patrol already empty cities with loudspeakers, urging people to stay at home, and threatening sanctions that in fact could not be applied. Leaving aside for a moment the question of social isolation’s “thinkabilty,” what I am proposing here is that an enormous percentage of people actually wanted to isolate themselves and enact social distancing, but they were forbidden to do so. These were (and still are) the people that are forced every day to go to work in crowded, increasingly limited public transportation, or by cars that kill hundreds of workers every year in accidents occurring in long commutes to and from work. These are also the people who work in manufacturing industries where it is impossible to practice distancing or access disinfectants or facemasks. These industries cause more than three deaths per day in work accidents in Italy. And these are industries subordinated more and more to German value chains that keep the highest value-added production steps in Germany (Bellofiore et al. 2019).

Many of those workplace deaths occur in industrial agriculture, a sector that at the time of writing is calling for more workers to go to the fields because of the increased demand from the retail sector—farmlands that in Italy as in the entire continent (Seiser 2006) are getting bigger every year at the expense of small farmers under pressure from international capital, but that are now unable to use an exploited, temporary transnational labor force because of restrictions on people’s movement across borders. It took several small wildcat strikes and even one national general strike to push to the surface of public debate the fact that state decrees and other measures dictated by Confindustria (the Italian association of big industrialists) kept non-essential workplaces open, workplaces where people died every day even before the lockdown and where infections still spread until this day. Independent estimates suggest that around half of the workers still forced to work could have in fact stayed at home. So much for the biopolitics of state-imposed confinement.

With the help of Gavin Smith’s (2006) pointing to “the logic of capital [a]s the real that lurks in the background” (itself a quote from Žižek 1999), I suggest that the Taboo object to be avoided desperately is class. The carnage we have been seeing during these past weeks is the same as was happening before, albeit at a slower, but nonetheless grinding pace, and which reached the same number of deaths projected for the present epidemic in Italy in about a decade. Being unable to look at class (since the concept has been declared unthinkable), one has to turn their head from that reality. But the daily death toll increase has forced everyone to confront the hard-to-believe dystopian present. We are now unable to un-see, and must fix our eyes for weeks on the mass deaths occurring in the healthcare system that we took for granted. There is now a widely felt need to identify causes for the death toll. The Italian public now substitutes walkers for workers. And the enemies of public health are being misunderstood as those who do not stay at home, instead of those who force people to be the victims of capital—capital that for a long time now has pushed for cuts to welfare workers’ rights, and wages. Now, a part of that same working class is fighting to overturn the narrative, and to throw off the blanket of denial that hides the structural inequalities that manifest in the pain described by Silva.

Another disconnect seems to be lurking, though. One that will probably be barely noticed in mainstream discussions in the coming months, due to the usual geographical distance that helps create cleavage between humanities, and which divides privileged populations and the expendables of the “Sacrifice Zone” (Hickel 2017). This chasm has been temporarily bridged by the fact that this virus hit the centers of global capital first. Economic historian Adam Tooze reminds us that although the Spanish Flu is remembered as a Western tragedy, it hit the colonial world much harder. And even if the last news available to me did not yet confirm such a trend for the present pandemic, the economic collapse that is going to be much worse than that of the great recession has plunged Third World countries’ currencies into what seems just the beginning of an economic disaster.

April has begun, and many believe that there can be no return to the way the world was before the pandemic. If we would want to apply the concept of liminality, then, we could begin to ask: what are the secret symbols we need to (re)learn, and what kind of new state are we going to enter? And we should recognize the constraints that structured the terrible normality that we left behind.

ANDREA TOLLARDO is a PhD candidate at the University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy. He works on the anthropology of work in Europe with special reference to mining and migrant labor and to the Alps.

References

Bellofiore, Riccardo, Garibaldo, Francesco, and Mortágua Mariana. 2019. Euro al capolinea? La vera natura della crisi europea. [Euro at the End? The True Nature of the European Crisis]. Torino: Rosenberg and Sellier.

Hickel, Jason. 2017. The Divide. A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. London: Penguin Random House.

OECD (2020), Hospital beds (indicator). DOI: 10.1787/0191328e-en (Accessed on 08 April 2020).

Remotti, Francesco. 2011. Cultura. Dalla complessità all’impoverimento. [Culture. From Complexity to Impoverishment]. Bari: Laterza.

Robbins, Joel. 2013. Beyond the suffering subject: toward an anthropology of the good. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.), 19: 447-462.

Seiser, Gertraud. 2006. ‘Healthy Native Soil’ Versus Common Agricultural Policy. Neo-nationalism and Farmers in the EU, the Example of Austria. In Andre Gingrich and Marcus Banks, eds., Neo-nationalism in Europe and beyond. Perspectives from Social Anthropology, pp. 199-217. New York: Berghahn Books.

Silva, Jennifer. 2019. We’re Still Here. Pain and Politics in the Heart of America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Turner, Victor. 1967. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press 1970 paperback.

Žižek, Slavoj. 1999. The ticklish subject: The absent centre of political ontology. London: Verso.

Cite as: Tollardo, Andrea. 2020. “No return to old normalities: Reflections on a time of passage in locked down Italy.” FocaalBlog, 9 April. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/04/09/andrea-tollardo-no-return-to-old-normalities-reflections-on-a-time-of-passage-in-locked-down-italy/

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.