The workshop “Geographies of Markets”—hosted over three days in mid-June 2017 by the Karl Polanyi Institute of Political Economy at Concordia University, Montréal—gave scholars from a wide range of countries and disciplines an opportunity to assess the continued relevance of the Polanyian critique of “market society.” Even if this critique lacks the formal rigor of neoclassical economics, even if Polanyi’s concept of market exchange fails to capture the institutional intricacies of contemporary markets, and even if the man himself was very much a European intellectual of his age, his approach still appears to provide the best scientific foundation on which to build global political and normative alternatives to neoliberal hegemony. Today, however, his geographic binary between East and West, like his ideal types of redistribution and market exchange, all need careful reappraisal.

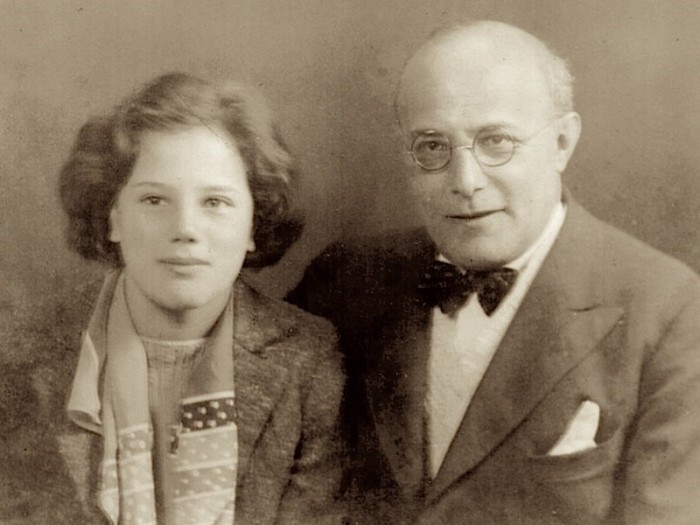

Karl and Kari Polanyi in 1938 when she, aged 15, accompanied him to one of his lectures in southern England organized by the Workers’ Education Association (photograph courtesy of Kari Polanyi-Levitt).

Debating market(s) in Montréal

Christian Berndt, Jamie Peck, and Norma Rantisi, conveners of the workshop “Geographies of Markets” in Montreal, 15–17 June 2017, posed searching questions concerning the ubiquity of markets in our contemporary globalized world. Although economic geographers were prominent among the participants, no one indulged in arid cartographic exercises. All 12 sessions engaged with central theoretical, methodological, and normative issues pertaining to market(s). Most participants drew on recent empirical research, ranging from agricultural land in Guatemala to affordable housing in South Africa, and from ethnicity-based employment agencies in Chicago to student loans in Australia. Many engaged in one way or another with financialization. Most made at least tenuous connection to the work of Karl Polanyi—which was entirely appropriate, as the meeting took place in the immediate proximity of his archive and was ritually opened by his daughter, Kari Polanyi-Levitt.

Professor Kari Polanyi-Levitt (photograph courtesy of the Karl Polanyi Institute of Political Economy).

Polanyi characterized nineteenth-century laissez-faire as a disembedding of the economy from society. But he also emphasized the thoroughly political character of this process, in terms of both state power and societal response through countermovements. The ambivalences of this (dis)embedding continue to be debated in the academic literature, reflecting decades of neoliberal hegemony during which the logic of competition and individual choice has been significantly extended. Market ideology has colonized vast domains previously ordered by other principles. As an advocate of democratic socialism, Karl Polanyi can be contrasted to Friedrich Hayek, for whom democracy is a potential obstacle to efficient allocation by means of spontaneous market forces. Political differences aside, however, both Polanyi and Hayek recognize the omnipresence of the state. Arguably, drawing on the Austrian tradition of economic thought they shared, both fail to grasp the interior workings of markets and end up theorizing “the market” in simplified, even essentialist ways.[1]

How to overcome “market essentialism” was the main gauntlet laid down by the conveners of this workshop. Polanyi is the epitome of an institutionalist economic historian when he explores the embeddedness of preindustrial economies, including the role of markets and money. But when it comes to the integrated systems of industrial capitalist markets, he does not question the textbook models or the reality of the “economistic fallacy.” Market is an empty signifier, a void: institutions are elsewhere. In fact, participants argued, once the analyst looks inside the black box labeled “market,” it turns out to be saturated in institutions, legal and political as well as technological and economic in narrower senses. Marketization is also a moral project, provided that “moral” is not restricted to the well-known gemeinschaft evocations of Ferdinand Tönnies or E. P. Thompson. Irrespective of ethical dimensions and distributive consequences, markets are always about power. Many markets, none more so than new financial markets, are better seen as highly regulated allocative bureaucracies, which leave little or no scope for choices and individual haggling over prices.

The principal factor uniting the assembled geographers, political economists, sociologists, and anthropologists in the sanctum of Karl Polanyi was not so much unconditional solidarity with this master as antipathy toward the theories of mainstream economics. Neoclassical economics was implicated in the destruction of social cohesion as well as in environmental catastrophe. But there was no consensus on how concerned academics should respond. Few seemed to think that Polanyi’s approach could be elaborated as a head-to-head epistemological alternative to the models of the economists. Polanyi operates at a different level: but does the greater empirical realism of his approach inevitably imply a weakness? Some participants seemed ready to concede epistemological superiority to the economists while justifying their critique via normative, political positions. Others insisted that dominant models based on methodological individualism and erroneous assumptions about actors’ behavior be contested, since they added up to bad, worthless science. Several suggested complementing Polanyi’s vision with more elaborately worked out compatible approaches, such as those of regulation and conventions theory. Gilles Deleuze’s theorizing of “the fold” and Michel Callon’s recent work on agencement have also found a following among geographers.

In several sessions, the ideal types of state and market melted away and everything became “co-constitutive.” If any concrete market is a complex amalgam of institutions, it is unrealistic to view it as a realm that the state can regulate, as it were, “from outside.” Often the market is itself a mechanism of regulation, notably financial markets, where the state is just another player in the game. The politics, too, become murky. Finance might seem to be parasitic on the real economy, yet some participants pointed out that “social finance” might function progressively as part of a countermovement (e.g., in the growing popularity of “green bonds,” reflecting awareness of the challenges of climate change). The production of entrepreneurial subjectivities around the world may be emancipatory for some, even when it means a concomitant decline in the rights (or entitlements) of social citizenship for the majority. Without necessarily giving up the political dimension, some participants preferred to emphasize the role of sociotechnical devices in furthering processes of marketization.

From market socialism to market populism in Hungary

At times, the cocktails of heady intellectual inspiration became too intoxicating for my jet-lagged brain. As usual when this happens, I tried to translate the sophisticated arguments of my fellow participants into the context of concrete transformations in rural Hungary (which I discussed in my own presentation). Forty years ago, it seemed clear to me, to other academic observers, and to the government and citizens of Hungary that a basic distinction could be drawn between the principle of the market and the principle of redistribution by the socialist state. Hungary was notable for the extent to which it had extended the scope of the former, but the market remained encompassed by the institutions and principles of socialism (hence “market socialism”). In key sectors—not just industry but also urban housing—the state imposed its preferences and market logics played only a subsidiary role (see Szelényi and Konrád 1979). The market principle was in some respects much more extensive in the rural sector (certainly as far as housing was concerned). I documented in the 1970s how the market for hogs was managed effectively by the state, which enabled village-based cooperatives to enter contractual relations with both household producers and state-processing enterprises. The hybrid system worked well for consumers in the cities (where most of the produce ended up, though some was exported). At the same time, it enabled unprecedented material accumulation and civilizational improvement in the countryside, where unemployment was unknown. But the recourse to material incentives without an ethos of competition and without a land market dissatisfied the neoliberal economists, both in Hungary and abroad. They complained about underemployment and other inefficiencies; for them, no socialist simulation of market mechanisms in certain realms could substitute for the real thing right across the board.

Then, after 1990, the real thing arrived, in the village of Tázlár as in the rest of the country. The land was privatized, the cooperative disintegrated. Many villagers were initially enthusiastic about these developments, because they had never been reconciled to socialist ideology and the diminution of their property rights. Later they realized that stronger property rights are of little use when markets no longer function and the entitlements of citizenship are undermined. They are puzzled that no one wants their hogs any longer and that the cost of raising them is greater than the purchase price of foreign meat in the German- or British-owned supermarkets in the nearby towns. It is the same story with wine: villagers can no longer find buyers for their product, while the Hungarian market is flooded with cheap Italian and Spanish wines. Not so readily available on the local market are jobs: many villagers nowadays face a choice between enrolling for local workfare schemes or joining the exodus to work in one of the prosperous western member states of the EU.

Tesco stores (here in Szeged) are well established and popular throughout this region of Hungary (photograph by Chris Hann, 2013).

For Karl Polanyi, land and labor are “fictitious commodities.” Collectivization and guaranteed employment are taken for granted in the democratic socialist society, which he regretted never having experienced in his own life. Many villagers in Tázlár who did experience socialism, albeit not in democratic form, look back with nostalgia at the kind of managed markets they knew in the 1970s and 1980s. That Polanyian model is above all pro-society. It seems more attractive than the Hayekian model that is tearing families and communities apart nowadays. The co-constitutive institutions of geographically ever more extensive markets contribute to reactionary populist politics at local, national, and supranational levels.

Hayek and Thatcher versus Polanyi and Polanyi

Kari Polanyi-Levitt was born in Vienna 94 years ago and lived through the greatest tragedy of what her father termed the “double movement” (she accompanied him to England in 1933 when it was clear that the family had no secure future in Austria). She is concerned by what she observes in Hungary today, and links these developments to the continuing distortions of global capitalism and above all to what she has termed “the great financialisation” (Polanyi-Levitt 2017). Kari insisted in her opening address to the workshop that a “world market” was no more feasible or desirable today than it was in her youth, when her father developed his withering analysis of the dangers of blind adherence to the gold standard. She stressed the centrality of his concept of “society” and how he would have rejected the two famous dicta of Margaret Thatcher, according to whom there was no such thing as society, just as there was no alternative to the implacable laws of neoliberal economics. Kari had a distinguished career as economist, and the active cultivation of her father’s legacy ties in seamlessly with her own engaged scholarship (see in particular Polanyi-Levitt 1990). However, as a specialist in what used to be termed the Third World, she does not hesitate to critique Eurocentric limitations in her father’s work. She drew attention in her speech to the “return of Asia,” as evident in the fact that it now produces the same share of world GNP that it produced in the early nineteenth century, before Asia fell victim to the depredations of the North Atlantic countries.

While this workshop reinforced notions of confluence and the inevitable entanglement of state and market, at the end I still felt some concern about the political implications of some of the cutting-edge scholarship. Surely we cannot dispense altogether with the opposition that Karl Polanyi set up between (market) exchange and redistribution? We may be condemned to live with thoroughly institutionalized markets all over the planet, but can we reach at least minimal agreement on certain rules and boundaries? If the hegemon unilaterally pulls out of the Paris environmental accords, how is the new coexistence to be negotiated? Or is the ongoing neoliberalization of the European Union an indication that the Thatcher-Hayek vision of economy and society will prevail over that of Polanyi and Polanyi?

This article originally appeared on the REALEURASIA Blog on 21 June 2017. Light edits were made, and punctuation, spelling, and citations were amended to conform to the FocaalBlog style guide.

Chris Hann is Director of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany. He is currently leading the ERC project “Realising Eurasia: Civilisation and Moral Economy in the 21st Century.”

Note

[1] My own interpretations have been much influenced by Gareth Dale (2010, 2016).

References

Dale, Gareth. 2010. Karl Polanyi: The limits of the market. Cambridge: Polity.

Dale, Gareth. 2016. Karl Polanyi: A life on the left. New York: Columbia University Press.

Polanyi-Levitt, Kari, ed. 1990. The Life and Work of Karl Polanyi: A Celebration. Montréal: Black Rose Books.

Polanyi-Levitt, Kari. 2017. “From great transformation to great financialization.” In Karl Polanyi in Dialogue: A Socialist Thinker for Our Times, ed. Michael Brie. Montréal: Black Rose Books.

Szelényi, Iván, and György Konrád. 1979. The intellectuals on the road to class power. Brighton: Harvester Press.

Cite as: Hann, Chris. 2017. “Hayek versus Polanyi in Montréal: Global society as markets, all the way across?” FocaalBlog, 11 July. www.focaalblog.com/2017/07/11/chris-hann-hayek-versus-polanyi-in-montreal-global-society-as-markets-all-the-way-across.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.