This post is part of a feature on anthropologists on the EU at 60, moderated and edited by Don Kalb (Central European University and University of Bergen).

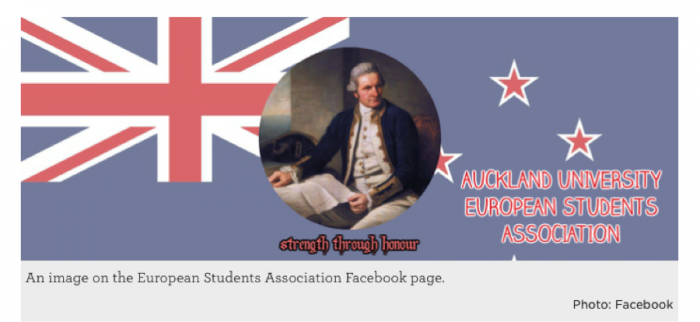

Earlier this year, a curious incident occurred in Auckland that ignited a heated debate over the meaning of the term “European.” A new student club calling itself the Auckland University European Students Association announced it was withdrawing its applications to affiliate to the university on the eve of the new semester’s orientation week. The withdrawal came after members of the club were threated with violence and accused by people both on and off campus of racism. This controversy erupted because of the images posted on the group’s website, including Celtic symbols used by US white supremacists and paintings depicting the unification of Germany. The group’s Facebook page included an image of Captain Cook and the motto “our pride is our honour and loyalty,” a phrase reminiscent of the Nazi SS slogan, “my honour is called loyalty.”

Critics saw this as a thinly veiled attempt to promote a white nationalist agenda. Yet the fledgling club’s president, who refused to be named, dismissed this as slanderous, insisting that the club, whose goal was to celebrate European culture and history, was open to any ethnicity, viewpoint, or belief. If anyone was fascist, came the retort, it was those who used intimidation and threats of violence to close down free speech. The university itself found no evidence of discrimination or racism to warrant banning the club. However, New Zealand’s race relations commissioner said she would be keeping an eye on the group. A week later, another group calling itself Western Guard plastered a series of white supremacist posters across the campus calling for the prevention of “white genocide.” These included the phrases “white lives matter,” “let’s take our country back,” and “Hey white man! Only you can prevent white genocide.”

I raise this incident because it highlights a problem facing the European Union today: the ambiguity and contradictions around the term “European” and the appropriation of that term by groups on the Far Right. Pope Francis in his address to mark the EU’s 60th birthday told European leaders that they need to show more “solidarity” with one another and resist “false forms of security” if they are to defeat populism and revive the integration project (Polliti 2017). However, populists and anti-EU parties may also find solidarity in a shared, albeit different, notion of Europeanness.

To the question “what is a European?” most European themselves don’t seem to have a clear answer, and there is little consensus on the topic. In terms of marketing, “European” is not a very successful brand. This is reflected in the fact that “Made in Europe” (compared to, say, “Made in Italy” or “Manufactured in Germany”) is seldom used as a label for consumer goods. Part of the problem with defining “what is European,” I suggest, is the difficulty defining what is “Europe.” As historian Hugh Seton-Watson wrote more than 20 years ago, “The word Europe has been used and misused, interpreted and misinterpreted, in as many different meanings as almost any word in any language” (1985: 9).

Contrary to popular belief and centuries of cartographic misrepresentation, Europe is not a continent or a “culture area.” It is an arbitrary conceptual construct. As William Wallace summed it up, Europe is an “imagined space,” and its boundaries are a “matter of politics and ideology rather than geography” (1990: 7). Moreover, those boundaries have shifted over time and continue to be in flux, particularly with the instability in the East and territorial claims of Putin’s Russia. Europe, as anthropologists like to point out, is a contested symbolic entity that shares much in common with other broad geopolitical categories like the “developing world,” “the West,” and “the Orient”—none of which represent a precisely delineated territory. As Edward Said wrote, “Orientalism is never far from … the idea of Europe, a collective notion identifying ‘us’ Europeans against all ‘those’ non-Europeans” (1978: 7). In this respect, Europe and “European” are not so much “empty signifiers” but rather heavily freighted words that operate as what Edwin Ardener called “blank banners” (1971: xliv). They provide a convenient flag under which all sorts of disparate groups can rally together but always against some perceived outsider or enemy. The question “what is a European” therefore requires us to probe into the realms of subjectivity, emotion, belonging, and identity—and how these are mobilized for political ends.

As I discovered working in Brussels, the European Union has long sought to wean European citizens from their attachments to nation. EU policy makers frequently complain that Europeans do not feel sufficiently European in ways that spill over into loyalty and affection toward the EU or its institutions. That is why the EU has expended so much time and money in trying to devise ways to create and promote European identity by, among other things, inventing a European flag, anthem, passport, and currency (Shore 2000), as well as drafting a lofty declaration on European identity, that all do little beyond affirming liberal democracy and the pursuit of economic progress. The 1973 declaration was one of the first official attempts to forge European unity around the idea of Europe as heir to the Enlightenment tradition (European Commission 1973). But it also illustrates how forging or strengthening “European identity” invariably means defining who is not European: those outsiders and barbarians at the gate against whom Europe defines itself. Historically, the threat of invasion from non-European has always been a catalyst for promting European identity. During the Cold War, being European was defined largely against Soviet Communism. Under the presidency of Jacques Delors, the European Commission tried to promote the idea of Europe as an economic bloc in competition with Japan and the United States. Today, as in the time of the Crusades, Europeanness is increasingly defined in opposition to the Muslim world.

European identity and the rise of Islamophobia

Yet one of the most significant recent developments in Europe is not so much the rise of the Far Right but the attempts to unify these parties under the banner of Europe against Islam. For example, in 2012 the Far Right English Defence League organized a Euro-wide rally in the Danish city of Aarhus in an effort to set up a European anti-Muslim movement (Pearse 2012). At the same time, President of the National Front Marine Le Pen was giving speeches denouncing the “Muslim occupation” of parts of France. In Belgium, Vlaams party leader Filip Dewinter proposed a quota on the number of young Belgian-born Muslims allowed in public swimming pools. He also called Judaism “a pillar of European society,” claiming that “multi-culture … like Aids AIDS weakens the resistance of the European body” and that “Islamophobia is a duty.” Matti Bunzl was perhaps the first to analyze this phenomenon. Whereas anti-Semitism in the 20th century was mobilized as part of the project for nation building, he argued, today Islamophobia is being mobilized as part of the project for creating a supranational Europe: “Islamophobes are not worried about whether Muslims can be good Germans or Danes. Rather, they question whether Muslims can be good Europeans.” Bunzl concluded with the chilling prediction that “Islamophobia threatens to become the defining condition of the new Europe” (2005: 449).

This brings us back to the Auckland University European Students Association and the contested semantics of the term “European.” Was this yet another thinly veiled manifestation of Islamophobia? The club’s president denied its promoting white supremacism, but the dog-whistle politics were clearly audible. In New Zealand, “European” means different things and is often used to differentiate pakeha (New Zealanders of European descent) from Maori. But as in Europe, “European” is a label increasingly embraced by groups on the Far Right. This raises a larger point about Europe’s changing political landscape and the contradictions in the EU project for ever-closer union. For much of the 20th century, the idea of Europe was closely associated with the ideals of reason, progress, liberty, tolerance, fraternity, and constitutional government. According to its own historiography, the EU was the embodiment of the Enlightenment project and a beacon for liberal democracy. As Eric Wolf wrote of the West, Europe’s history was portrayed as a genealogy of progress and “moral success story” (1982: 42). Today, however, “Europe” and “European” seem to be terms increasingly associated with the darker side of modernity. For many people living in the periphery of the Eurozone, particularly in Greece, Europe has come to symbolize not liberty and democracy but austerity, rule by technocrats, and loss self-government. But perhaps these contradictions were always latent in the idea of Europe, just as they were in the ideas of nation and nationalism.

Cris Shore is professor of anthropology at the University of Auckland and former director of its Europe Institute.

References

Ardener, Edwin 1971. “Introductory essay: Social anthropology and language.” In Social anthropology and language, ed. Edwin Ardener, ix–cii. London: Tavistock.

Bunzl, Matti. 2005. “Between anti‐Semitism and Islamophobia: Some thoughts on the new Europe.” American Ethnologist 32 (4): 499–508.

European Commission. 1973. “Declaration on European identity.” In General report of the European Commission. Brussels: European Commission. http://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/1999/1/1/02798dc9-9c69-4b7d-b2c9-f03a8db7da32/publishable_en.pdf.

Pearse, Damien. 2012. “EDL holds far-right rally in Denmark to unite ‘anti-Islamic alliance.’” The Guardian, 31 March. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2012/mar/31/edl-far-right-rally-aarhus-denmark.

Polliti, James. 2017. “Pope Francis says EU leaders should show ‘solidarity’ with each other.” Financial Times, 25 March. https://www.ft.com/content/21c655b8-4100-3c6e-add5-58aaeae8d769.

Said, Edward 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon.

Seton-Watson, Hugh. 1985. “What is Europe, where is Europe?” Encounter 65 (2): 9–17.

Shore, Cris. 2000. Building Europe: The cultural politics of European integration. London: Routledge.

Wallace, William. 1990. The transformation of Western Europe. London: Pinter.

Wolf, Eric R. 1982. Europe and the people without history. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cite as: Shore, Cris. 2017. “What is a European? Solidarity, symbols and the politics of exclusion.” FocaalBlog, 5 April. www.focaalblog.com/2017/04/05/cris-shore-what-is-a-european-solidarity-symbols-and-the-politics-of-exclusion.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.