Antonio Gramsci, condemned by Benito Mussolini to twenty years in prison, wrote his celebrated prison notebooks while sitting in a succession of fascist jails. He reflects on some of the following questions: why is Mussolini in power, while he and so many other leftists are in prison, dead, or in exile? What explained the defeat of the once powerful Italian left? How could fascist and other right-wing forces be defeated? Twenty-first century America is not mid- twentieth-century Italy, and Donald Trump is not Mussolini. Nonetheless, for those seeking to understand Trump’s electoral victory, and searching for ways that this American-produced, authoritarian populist might be effectively challenged, Gramsci’s notebooks make interesting reading.

For instance, Gramsci’s concept of senso comune,[1] normally translated as “common sense,” can help explain the nature of Trump’s appeal to so many voters—an appeal that has bewildered so many on the left. Those who read the notebooks in English, as I do, need to be aware, however, that senso comune is a far more neutral term than common sense, one that lacks common sense’s positive connotations, referring rather to all the taken-for-granted “knowledge” that has accumulated in a given time and place.

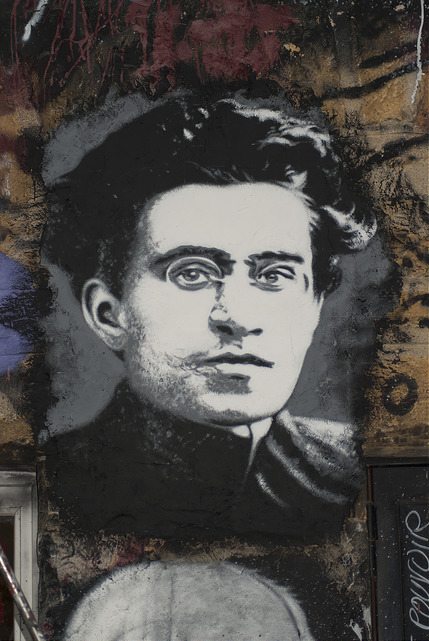

Antonio Gramsci, painted portrait in Saint-Romain-au-Mont-d’Or, Rhone-Alpes, France (© 2015 Abode of Chaos, via Flickr).

The beliefs and assumptions that constitute common sense (senso comune) are extraordinarily heterogeneous and often contradictory. One individual’s or one group’s common sense may seem anything but that to those inhabiting a different time or place. What ties it together is that this knowledge does not need to be proved or supported by evidence; if its “truth” is not immediately obvious to any “reasonable” person, then it is not common sense. Common sense might be seen as the polar opposite of critical thinking, which challenges us to take nothing for granted and to meticulously scrutinize the evidence for any claim. Politicians of all stripes, especially those of a populist bent, like to present their particular “truths” as common sense and, by definition, beyond debate. And this has certainly been Trump’s strategy; the very vagueness of Gramsci’s concept of common sense—its broad, inclusive quality, its encompassing of facts that shift over time—makes it a particularly useful way of analyzing the nature of Trump’s appeal.

The former star of reality TV has proved to be remarkably adept at constructing a narrative that seems to his supporters to be no more than common sense, even if out-of-touch elites fail to recognize it. This is a narrative of us and them, where the “them” includes Mexicans who control the drug trade and take jobs away from native-born Americans, Muslims (all potential terrorists), and a government bent on repealing the Second Amendment. Woven together into an emotionally persuasive whole are a series of assertions, rooted in a deep racism, about the dangers facing native-born Americans. It is no accident that when Trump first began flirting with the idea of running for president, he continually questioned President Obama’s citizenship with the birther lie—a lie founded on a gut sense that no one who looked like the president and had the name Barack Hussein Obama could possibly be a genuine American. A bumper sticker I saw in Maine this summer reflects this deep resentment and the racism that underlies it: “To Hell with Diversity: Keep America American.”

Trump’s success in connecting with such a broad swath of “ordinary” Americans was in large part based on endlessly repeated sound bites that seemed to his supporters to be simple common sense. His rallies were not about fact-based arguments but rather claims that ran along grooves carved out by the Tea Party, which asserted, for instance, that an overreaching state was denying just entitlements to those who had earned them while lavishing benefits on immigrants and other unfairly privileged minorities. Trump spoke to the same sense of loss and injustice expressed by a male Tea Party supporter: “I want my country back!” (quoted in Skocpol and Williams 2012: 7) The belief that America has lost its moral moorings and is heading in the wrong direction is widely shared in rural America, in the Rust Belt states, and by the older, white working-class men who form the core of Trump supporters. The great dealmaker assured his audiences that they can have their country back: all it takes is for the right people to be in power. His mobilizing slogan, “Make America Great Again,” conjures up a once golden world, one in which “ordinary” Americans, assumed to be white, not only had good-paying jobs but could speak their minds and tell jokes without fear of the political correctness police.

Demonstrating Trump’s factual inaccuracies, by providing evidence of his lies, had no hope of dislodging this profound sense that he, unlike the beltway elites, grasped the reality they, ordinary white Americans, were living: America was no longer great. From Trump, they heard articulated all their own frustrations and anger at the metropolitan elites’ perceived disdain for them, their way of life, their worldview. That this was coming from a New York real estate mogul, born into wealth (whose own life hardly reflected the values supposedly held by conservative Republicans) was not important. All that mattered was that Trump, honed by his years as a reality TV celebrity, was able to give voice to their anger in a language they recognized: a language rough and unpolished but “authentic,” which gave all those elites the middle finger. The vision of turning the clock back, presented in not the slick language of experts and spin doctors but an authentic-sounding inarticulacy, rang so true to what those who felt excluded and belittled by Washington’s power elite believed—namely, that what had once been, could and should come again—they did not need to hear detailed plans of how it might be achieved in practice. In their eyes, its simple common sense rightness was proof enough.

Clinton’s dogged laying out of specific policies designed to tackle specific problems, however fact-based and practical, had none of her opponent’s emotional appeal. And without a compelling, common sense narrative, no progressive candidate has a chance. Gramsci’s reflections on the relationship between knowing, understanding, and feeling are pertinent here. It is crucial, he argued, that would-be progressive intellectuals and politicians connect emotionally with those they would persuade. Being an effective intellectual or politician means “feeling the elementary passions of the people, understanding them and therefore explaining and justifying them in the particular historical situation … One cannot make politics-history without this passion” (Gramsci 1971: 418). Bernie Sanders demonstrated his understanding of this with his continual reiteration of a simple, common sense message of increasing economic inequality, which spoke directly to the lived experience of so many, perhaps particularly to millennials who reached adulthood during the Great Recession and the subsequent anemic recovery that seemed only to have exacerbated inequality.

Gramsci is a particularly interesting thinker to return to in this economic and political moment because while he was very much a Marxist who believed that the material circumstances of people’s lives shaped their worldviews, he never saw those material circumstances as determining those worldviews. People fashion their understandings of the worlds they inhabit from the narratives they have available to them; all of us, even the most sophisticated theorists, are molded by the ideas and beliefs of the world, or worlds, in which we are socialized. One of the defining characteristics of hegemony, perhaps Gramsci’s most influential concept, is the ability of those in power to make the way the world appears from their vantage point, the authoritative viewpoint. Alternative narratives that challenge the hegemonic status quo are characterized as unrealistic, coming from “special interests,” or simply wrong. Those who would oppose hegemonic narratives face a far harder task than those who simply reproduce them. A key part of that task is to make alternative narratives available to the mass of the population in a common sense form that people recognize as true to their experience. In other words, any serious challenge to existing power relations demands both thought-out, intellectually coherent accounts of the world as it is and “new popular beliefs, that is to say a new common sense and with it a new culture and a new philosophy which will be rooted in the popular consciousness with the same solidity and imperative quality as traditional beliefs” (424).

But from where do such “new popular beliefs” come? Unlike some Marxists, Gramsci never believed that intellectuals alone could provide fundamentally new understandings that reflect the world as seen from the vantage point of the subordinated and oppressed. Intellectuals for him certainly play a crucial role in the generation and dissemination of such understandings, but ultimately, effective oppositional narratives are the fruit of dialogue between intellectuals and the collective experience of those who are subordinated, the groups the notebooks term “subalterns.” Intellectuals are necessary because while subalterns certainly generate their own explanations of their oppression, these remain incoherent and fragmentary. It is the role of intellectuals (a very broad category in the notebooks) to bring these fragments together and to render the incoherent coherent. However, they cannot do this without the raw, fragmentary beginnings generated by subaltern experience itself: “Is it possible that a ‘formally’ new conception can present itself in a guise other than the crude, unsophisticated version of the populace?” (342). Progressive intellectuals have to listen to these embryonic beginnings, make them more sophisticated and coherent, but then translate them into progressive “common sense.”

From where in the contemporary United States might new progressive, popular beliefs emerge, and how might they spread? One consequence of the decline of the left, and the ever-smaller role of labor unions, has been a dramatic shrinking of the spaces in which oppositional accounts of the world that challenge the triumphant capitalist narrative have room to emerge, develop, and spread. With a popular media that has shifted to the right over recent decades, for large numbers of people, the only explanations of the realities they experience are those they hear on Fox News and other right-wing TV stations, talk radio shows, and social media that tend to echo and amplify a view of the world that is deeply suspicious of government, and believe things would be better run if executives, not politicians, were in charge. Given this depressing reality, what spaces exist for the necessary dialogue between intellectuals and the raw experience of oppression? From where might alternative, oppositional understandings of the world emerge and become “common sense” narratives with the power to become “rooted in the popular consciousness with the same solidity and imperative quality as traditional beliefs”? Perhaps the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement offered one moment of hope.

The OWS slogan—“We are the 99 percent!”—is an interesting example of a progressive common sense that was powerful enough to compel politicians of all stripes to accept the existence of economic inequality. As Todd Gitlin has written, OWS created “a new center of gravity in what we are pleased to call ‘the national debate.’ Inequality of wealth was now widely recognized—and seen as a problem, not a natural condition. ‘The 1 percent’ and ‘the 99 percent’ were commonplaces” (2012: 232). “We are the 99 percent!” provided a powerful albeit vague narrative that spoke to a wide range of people. Anyone who felt that the decent life the American system was supposed to provide was slipping beyond their grasp could feel themselves included within the embrace of the 99 percent: those with degrees who had been left with a mountain of debt but no job; those whose homes had been foreclosed, not because they had borrowed recklessly but because the recession had cost them their jobs; workers whose hard-won benefits and pensions were being slashed as “unfeasible”; and jobless veterans. “We are the 99 percent!” provided a name for lived experience that demanded articulation. A major achievement of OWS with its occupation of a site associated with big capital was to create a space that allowed a new common sense to emerge. Intellectuals were present in the narratives, based on arguments made by progressive thinkers such as the economists Joseph Steglitz and Paul Krugman that framed the OWS dialogue. The army of occupiers brought their lived experience. One form the dialogue took was a forest of handcrafted signs, which were not the slick products of media professionals but rather authentic, heartfelt cries of pain, welling up from the day-to-day experience of inequality. The slogan that emerged out of this dialogue did not require explaining or substantiating; it simply captured the lived experience of inequality.

Trump’s common sense can only be confronted by an alternative common sense that is as emotionally powerful as that of the right. Even though it may soon have flamed out, the collective energy and enthusiasm of OWS, and the many occupations across the country, created collective spaces that generated the beginnings of just such a new common sense, the kind of progressive common sense for which Gramsci called.

Kate Crehan is a professor of anthropology (emerita) at the City University of New York. She has published extensively on Gramsci, most recently, Gramsci’s Common Sense: Inequality and Its Narratives (Duke University Press, 2016). Her other books include Gramsci, Culture and Anthropology (University of California Press, 2002), Community Art: An Anthropological Perspective (Berg, 2011), and The Fractured Community: Landscapes of Power and Gender in Rural Zambia (University of California Press, 1997).

Note

[1] For an in-depth exploration of Gramsci’s concept of common sense, see Crehan 2016.

References

Crehan, Kate. 2016. Gramsci’s common sense: Inequality and its narratives. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Gitlin, Todd. 2012. Occupy nation: The roots, the spirit, and the promise of Occupy Wall Street. New York: itbooks.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. Ed. and trans. Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Skocpol, Theda, and Vanessa Williams. 2012. The Tea Party and the remaking of Republican conservatism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cite as: Crehan, Kate. 2017. “Kate Crehan: Gramsci/Trump: Reflections from a fascist jail cell.” FocaalBlog, 18 January. www.focaalblog.com/2017/01/18/kate-crehan-gramscitrump-reflections-from-a-fascist-jail-cell.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.