The teachers’ campaign in defense of public education and against the neoliberal reforms being introduced by the Mexican government has ignited a new cycle of social struggles and an outbreak of violent repression in Mexico. This short article was written from within the barricade/encampment of San Cristobal de Las Casas (Chiapas), where, for nearly two weeks, organized teachers together with a supportive heterogeneous population are blockading the highway to Tuxtla Gutierrez—the state’s capital. The encampment of San Cristobal is one of the dozens of blockades that have been set up over the last few weeks all across the country.

*

In the early morning of Sunday, 19 June, in a joint operation, the federal and state police attacked with firearms organized teachers, students, and residents of Nochixtlán, a small town located some miles away from the city of Oaxaca. For one week the population of this community had being holding a barricade in resistance to the education reform being pushed through by the federal government. The aggression ended with the murder of eleven protesters. More than a hundred were injured, and eighteen people were arbitrarily removed from a funeral taking place nearby (having nothing to do with the picket) and jailed.

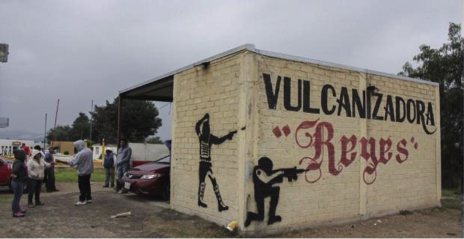

The National Security Commission hurriedly issued a statement declaring that its agents were totally unarmed—“they didn’t even carry batons,” they argued. However, the photos taken by a reporter of Cuartoscuro agency clearly show federal police agents triggering AR-15 rifles and 9mm guns against the crowd. One of these images, showing a uniformed man on his knees firing his assault rifle against the barricade from a nearby tire repair workshop, became viral on social networks, disproving the official version of the facts.

Few days after the shooting some anonymous street artists have painted a mural on that exact same spot, representing soldiers in the same position as they were portrayed in the above mentioned pictures.

This time, given the firm response of broad sections of the local population and independent media outlets, the federal police did not manage to pollute the crime scene and craft proofs incriminating third parties or the protesters themselves—as it happened, for example, with the massacre and mass kidnapping of Ayotzinapa (November 2014).[1] The government was therefore forced to change its narrative and to issue a series of rectifications aimed at, once again, justifying the internal warfare politics through which the country is currently being ruled.

Teachers of the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE), Latin America’s largest union, have been on indefinite strike since 15 May. They are arguing that the idea of “educational reform” is totally misleading since there is no sign of pedagogy in the legislation being approved by the government. The reform presents itself more like a labor and administrative restructuring involving constitutional changes, the imposition of a new contract, and the establishment of a national evaluation system for teachers as a prelude to massive layoffs. Secretary of Public Education Aurelio Nuño has systematically refused to establish a dialogue with the National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE, the leading board of SNTE). “Dialogue can not be established to negotiate on the educational reform,” he said.

Together with public health, land, and energy, education is part of the package of structural reforms being implemented by President Enrique Peña Nieto. They reflect a general process of reconfiguration of the Mexican state, responding to a new cycle of capitalist expansion and accumulation in the country. Indeed, an essential aspect of the seemingly “illogical” atrocities that the state is committing is that this violence assists the realization of tremendous infrastructural mega-projects that bring about enormous social and environmental impacts, such as the construction of new highways, airports, and dams; the massive implementation of monoculture systems in the countryside, and so on. These developments are functional to the new extractive policies for which the current administration has handed over 25 per cent of the national soil to (national and international) extractive enterprises.

Coincidence or not, on 1 June, just some days before the massacre of Nochixtlán, a new “scheme” was officially launched by the federal government, establishing “special economic zones” (SEZ) in the states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Chiapas. This program aims at providing these regions with the necessary infrastructure for the exploitation of their mineral, energy, and agricultural resources, facilitating a dynamic of accumulation by dispossession.

The seizure and exploitation of land and resources by international capital brings about aggression toward the populations inhabiting targeted territories. Any bonds between people and the spaces that they inhabit need to be disrupted. The enforcement of a rationality of plain profit requires that societies be fragmented, individualized, and made dependent on external forces. It requires the destruction of traditional forms of state institutionality as depositary of the universal values associated to the idea of “public.” What is at stake here is an ontological transformation—the production of a different form of life (a different humanity) in those regions of the south of Mexico that are mainly inhabited by indigenous groups and legally organized under collective forms of tenure.

“Ejidos” and “agrarian communities”[2] are egalitarian outcomes of the agrarian reform, which constituted one of the main political achievements of the Revolution of 1910, together with the education reform. These rural collectivities still hold a shared living memory of the Revolution, which motivates them to keep defending those lands from the predatory aggression of capital—against the geographic, economic, and social reconfiguration that this system imposes. Teachers have played a decisive historical role in constantly revitalizing and actualizing this memory, reproducing a national identity based on the principles of the Revolution and advocating an emancipatory pedagogy promoting autonomous and collective practices.

The rampant processes of militarization that the country is experiencing and the adoption of a strategy of internal low intensity warfare respond to the necessity of eroding the commons in favor of a “new” exploitative rationality. The logic of military operations as those witnessed in Ayotzinapa and Nochixtlán has to do with the production of chaos aimed at deterritorializing spaces toward the institution of, to use Fanon’s idea, “zone of non-being” where humanity is violated day after day. As a peasant told: “the politics of the government is to do away with communal life. They want you to leave your land, that you sell it—their aim is to individualize communities.”

In Chiapas, people are currently asking themselves if, with a local movement showing particular strength and determination, they will be the next victim of violent repression, after Oaxaca. Local entrepreneurs are urging the government of Manuel Velasco Coello to “apply the rule of law,” that is, to use force to evict the dissident teachers and their supporters holding blockades all around the region. The mayors of San Cristobal de las Casas and other neighboring towns have been accused by the movement to be contracting informal assault groups to attack the blockades. San Cristobal is home to the ALMETRACH,[3] a paramilitary organization responsible for the recent assassination (March 2016) of Juan Carlos Jimenez, a teacher actively campaigning against the education reform and for the right to land of local indigenous groups.

The paramilitarization of conflicts has become a main issue in Chiapas and Mexico in general, where armed gangs related to various levels of state power are operating in the shadows, without any defined material or geographic limits, and acting solely in the name of whoever is paying—be it a narco boss, a politician, a state agency, a multinational corporation, or a coalition interested in, for example, intimidating a group opposing the implementation of a mining project on their communal lands.

Interestingly enough, many of these groups are previous revolutionary peasant mass organizations that in the ’90s went through profound processes of depoliticization (also due to the polarization produced by the Zapatista uprising) and turned into rural corporative and clientelistic apparatuses, constantly looking for remunerative opportunities and power positions. Along with this process they fell under the control of political/economic powers and are now used as paramilitary service providers, playing a decisive role as counterinsurgent forces and fostering warfare and social chaos.

In this perspective the massacre of Nochixtlán directly relates to the events of Ayotzinapa. These tragedies have ignited a conflict that goes beyond the opposition to the education reform. An increasingly heterogeneous subjectivity has mobilized around it. “It started as a magisterial protest, but it quickly became a widespread popular movement,” said a union member. This is because the protest managed to catalyze a latent disposition in Mexican society that was failing to find a concrete and organized expression. “It is not a manifestation that overflowed. Rather, an overflow is manifesting itself,” would argue the Invisible Committee.[4]

The blockade/encampment of San Cristobal de Las Casas has turned into a rallying ground where every day a number of associations and independent groups are marching to show solidarity with the teachers and join their struggle. The area of several hectares is occupied by a diverse population that keeps it lively day and night. Several kitchens feed the protesters three times a day, and a number of local collectives have taken responsibility for coordinating cultural activities like the projection of films and documentaries and the organization of small gigs. Political meetings and assemblies are constantly taking place in the various regional tongues. A meticulously coordinated security commission is on duty to keep the camp safe. The access points to the area are constantly watched over and small brigades patrol the adjacent neighborhoods to detect eventual military or police activity. However, the national leadership of the teachers union (CNTE) has demanded the movement to remove all existing blockades in view of a strategy change. San Cristobal (among others) decided not to follow this directive.

In the meantime, the Zapatistas (EZLN)—who, just a few days before the massacre of Nochixtlán, had somehow predicted[5] that something alike could eventually happen—have suspended their participation in the CompARTE Festival, an international arts event to take place in Chiapas in July, which they themselves had been organizing over the last six months. The official reason has to do with the Zapatistas not wanting to hinder the teachers’ movement in this delicate phase. “To put it more clearly, the most important thing now, on this calendar and from the limited geography in which we resist and struggle, is the struggle of the democratic teachers.”[6] As a concrete act of solidarity, the Zapatistas have distributed tons of food among those who are on strike and conducting blockades on highways. However, the feeling is that the choice not to participate in CompARTE was dictated by security reasons. It might not have been prudent for the EZLN to expose themselves in such a risky conjuncture.

The organized teachers seem to be ready to pay the costs of resisting until the reforms collapse. As I said, the main danger that they are facing is violent repression. Arguably, this is the Mexican state’s current strategy, one of armed chaos in support of its capitalist plans of accumulation by dispossession.

The movement’s main challenge will be to keep control and not respond to provocations—avoiding to shift their politics into the field of war: a fertile one for the state/capital alliance.

Alessandro Zagato is research fellow in the Egalitarianism project at the University of Bergen. He is currently conducting fieldwork among rural communities in the south of Mexico. He has recently edited a volume titled The Event of Charlie Hebdo: Imaginaries of Freedom and Control.

Notes

1. For more information and a background on the “Ayotzinapa” case I recommend “After Ayotzinapa: building autonomy in a civil war.”

2. Ejidos are peasant collectivities occupying land given to them by the Mexican state after the Revolution (1910). Agrarian communities collectively manage a piece of land that was held by an “indigenous agrarian community before colonialism,” an ancestral property institutionalized by the postrevolutionary state.

3. Asociación de Locatarios de Mercados Tradicionales de Chiapas (Tenants Association of Traditional Markets of Chiapas)

4. My translation from Spanish.

5. “What’s next? Will they disappear them? Will they murder them? Seriously? The ‘education’ reform will be born upon the blood and cadavers of the teachers?”

6. EZLN 2016

Cite as: Zagato, Alessandro. 2016. “Teachers struggles and low intensity warfare in the south of Mexico.” FocaalBlog, 25 July. www.focaalblog.com/2016/07/25/alessandro-zagato-teachers-struggles-and-low-intensity-warfare-in-the-south-of-mexico.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.