Since 2012, we have carried out twelve months of urban anthropological research in Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city and its economic and cultural center. Until February 2016, however, we had not once visited the country’s capital, Naypyitaw, a planned city of immense size. It had not been a priority for our work, but we also had not been really keen on visiting: when the former military government began to relocate the capital in November 2005, away from cosmopolitan, multireligious, multiethnic Yangon, located at the mouth of the Andaman Sea, to a previously more or less vacant inland area, most commentators had been dismissive, bemused, or outraged.

Naypyitaw was variously denounced as a “vanity project” of the old generation of generals, based on their belief in astrology, and as a paranoid securitization measure to stymie an expected American invasion (Selth 2008). The rumors about a North Korean–built tunnel system and the factual existence of secluded military zones and retirement homes of former generals added difficulty to seeing the city in a positive light.

But it is hardly atypical for postcolonial societies to shift their capitals away from the coast toward the hinterland, traditionally the site of centralized power (see Schatz 2003); furthermore, the old kings in what is today Myanmar regularly built new capitals in the dry zone of the country (Gärtner 2011). From such a cultural-historical perspective, the move to Naypyitaw is just a delayed instance of a very typical pattern, both nationally and globally, and as such neither absurd nor irrational. The old colonial capital, Rangoon, as Yangon was called until 1989, had itself been the outlier, a city built by the British Empire for its own needs and purposes, far away from precolonial centers of power.

From Yangon, the capital is inconveniently located. It takes the better part of a day to reach, and, once in Naypyitaw, one requires a car for transit between “Hotel Zone South” and “Hotel Zone North” and the ministerial buildings, arenas, and museums as public transportation is undeveloped. The functional segregation of the city means that nothing can ever be reached on foot, and unlike Yangon, no host of taxis is dogging visitors, ready to drive them wherever.

Beyond such practical annoyances, the reporting about Myanmar’s new capital has been disparaging across the board. The criticisms and ridicule of a “megalomaniac metropolis” designed by reclusive autocratic generals basically write themselves—most simply as a colossal waste of money.

Despite or because of this, Naypyitaw immediately grabs your attention. Primed by the reports read and the first- and second-hand accounts heard, one is strangely alert to spot difference and digression from what could be considered “reasonable.” We found ourselves always on the lookout, trying to spy urban elements outlandish enough to out-crazy the crazy, to find extreme displays of reality loss in the place in the plains that the generals created as their “Abode of Kings”—the literal meaning of the name Naypyitaw. Due to the established tone for writing about Naypyitaw, everyone seems to arrive already with the expectation of finding absurdity and, even worse, waste and irrationality. As a planned capital, designed for a new Myanmar, it is not incidentally a foil for Yangon.

Thus, visiting Naypyitaw is instructive. It has thrown our experiences in Yangon into sharper relief. It also confronted us with further anthropological questions to keep us busy in the future.

For the purposes of this photo essay, we want to focus on one of these, the materiality of Naypyitaw, as manifested in its manipulation of and experimentation with space and scale. Particularly, it was the strange play between excessive space on the one hand and controlling designs bent on miniaturizing and condensing on the other that strongly shaped our experience of this city.

Supersize it! On the excess of space

One of the main experiences that Naypyitaw offers is an excess of space. Turning off the Yangon-Mandalay highway, the road soon widens; four lanes turn into eight. Visitors treat this road as a “sight”: cars stop in the middle of the asphalt plain, tourists get out and walk around, trying to find the best vantage point for a picture that might reproduce this odd experience. Some foreigners even used it for flippant car races (as the TV show Top Gear).

Enormous roundabouts punctuate the wide road. Despite the lack of traffic, there are police cars stationed at most of them. Rather than directing traffic as their colleagues in Yangon do, their presence seems a reminder that this empty space is stately, and therefore purposeful.

The contrast to Yangon’s notorious traffic jams is stunning, and we immediately felt relaxed, experiencing a physical sense of relief. As one gets closer to the parliament, a fenced-off fortress and arguably the center of the city, the road has literally ten lanes going in each direction.

The vastness of this infrastructure is reinforced by its visible lack of use. While there may be moments when the road sees actual traffic, it is clear that there are not enough cars in Naypyitaw to even remotely require such space.

The parliament building behind the treeline (200mm lens extended) (Photo: Judith Beyer/Felix Girke 2016)

Barring privileged access, the parliament itself can only by viewed from the street, and the enforced distance denies visitors a real appreciation of its size as well as a clear understanding of its layout. The effect to us was auratic—look, but don’t touch. The high black fence, which shields visitors from entering the compound with its two pylon bridges, and the golden replica of the very building one is trying to look at from a distance—a gilded icon in lieu of the edifice itself—add to its fortress character.

But the spatial generosity is not limited to the roads and the wide no man’s land in front of parliament. Entering hotel grounds, museum hallways, shopping malls, and other semipublic and representative places, the sense of extreme openness is reinforced. Nothing in Naypyitaw appeared cramped or crowded.

Can we even imagine a Naypyitaw where all that space is actually in use? Did its builders imagine it that way? Or did they plan to have a city marked by a disparity between space and inhabitants in perpetuity?

The Defense Services Museum, also relocated from Yangon, is a demonstration in how space can be wielded as a blunt instrument to stun and awe visitors. Again, most of this is space that is ostentatiously empty—even several busloads of visitors poured into the Museum grounds would not make much of a difference. But when we came, we were yet again the only ones.

Stretch of lawn between tracts of the Defense Services Museum (Photo: Judith Beyer/Felix Girke 2016)

With hardly any signage, no reception area, no flyers or leaflets available, we proceeded to the central point of the structure to see what we could find.

Getting out of the car, a friendly guide in military uniform led us to what we can only assume is the heart of the museum: the room called the Defense Services Museum and Historical Research Institute, an enormous exhibition through which the tatmadaw (armed forces) demonstrate their foundational role in the “well-being of the nation since antiquity.” Uniformed staff enthusiastically assured us that this museum was a gift from the army to the entire population, which, working together, would achieve a bright future for the country. The museum hosts numerous highly symbolic original artifacts, such as the very Union Jack that was lowered in 1948 to herald the end of British colonialism and the original items used by the legendary “thirty comrades” of the independence struggle in their team-building exercise suggestively known as the “blood-drinking ceremony” in the early 1940s.

Colonialism behind glass (Photo: Judith Beyer/Felix Girke 2016)

After intensive study of the Historical Research Institute, we left the museum several hours later and still wondered what we could have found in the other rooms and wings. The excess of the place had exhausted us.

The purified pagoda

If the parliament is the secular core of the city (as much as parliaments can be secular), and the Defense Services Museum is an odd and hypertrophic appendage, the city’s major pagoda, the Uppatasanti, appears intended as its (mono)religious and spiritual heart.

The roads to the pagoda with its slender spire plated in actual gold are as wide as in other parts of the city. Like Myanmar’s largest pagoda, the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, on which it is modeled very closely, it sits on a hill and is visible from afar. Uppatasanti is pointedly just one foot lower than Shwedagon.

Whereas the Shwedagon’s history is said to stretch back 2,500 years, the Uppatasanti was only recently finished, and its platform presents a stark contrast to the Shwedagon’s: where the latter hosts uncountable minor shrines and shady corners, the Uppatasanti stands alone. The platform is white and bare to a degree that makes one realize how cluttered the original in Yangon is.

Inside the Pagoda, there is again a lot of empty space; visitors can walk in an inward-facing circle around the centrally arranged Buddha statues (and a replica of Buddha’s tooth) or in an outward-facing circuit to study the large twenty-eight specially commissioned white marble carvings lining the walls.

Aesthetically, Uppatasanti fits with the rest of Naypyitaw—ambitious, ostentatious, even excessive—but sober (as much as a golden pagoda can ever be sober). To encounter this sobriety raises questions about the intent of the design and the contrast to Yangon.

Yangon is a glorious mess, studded with untidy additions and improvisations giving evidence of various historical interventions. Naypyitaw seems to reject this historical palimpsest. It is as if the military government pushed a reset button. Building Uppatasanti, for example, meant copying the country’s most sacred Buddhist monument, acquiring merit in the process, and restoring it to a past and possibly imaginary purity. As pure as the rest of Naypyitaw, where no church, no mosque, and no Hindu temple can be found: with a different sort of heritagization from Yangon’s focus on colonial architecture, Naypyitaw is utopian in projecting a pure past that never was.

Condensed heritage: A whole country in a park

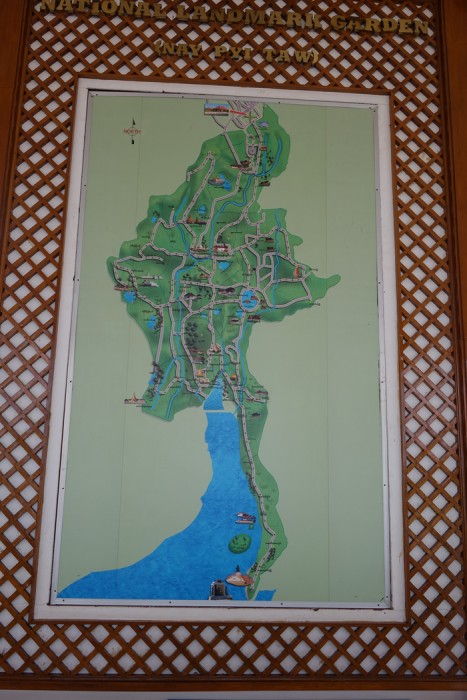

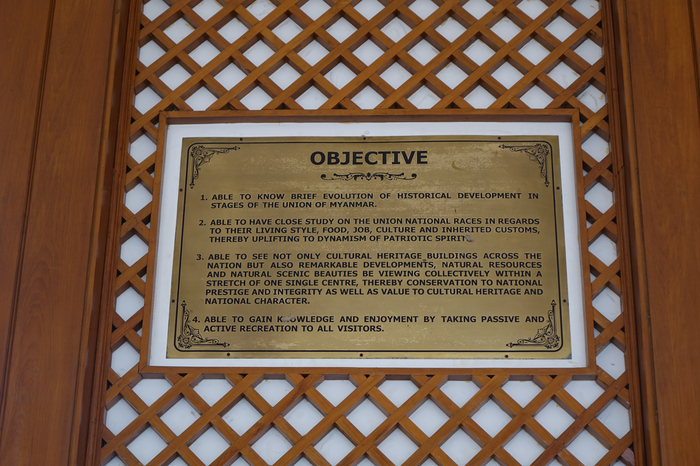

That the Uppatasanti Pagoda is just one foot shorter than Shwedagon is usually taken as a sign of respect for the original. But there are other places in Naypyitaw where we found a preoccupation with the art of condensing. There are thus two manipulations of space going on in Myanmar’s capital: next to supersizing roads and buildings, other aspects of what the military government considered worth displaying and performing in the new capital are realized through the condensation or miniaturization of “big things”—such as the country itself. At the very edge of the city lies the National Landmarks Garden, a theme park with the shape of Myanmar.

It seems to have been planned with clear objectives that were entirely derailed by its eventual implementation.

Ambitious objectives (Photo: Judith Beyer/Felix Girke 2016)

The declared intention of educating and edifying the public got lost when the attractions of the park were leased out to various private companies who turned them into attractions of dubious character such as placing a haunted house inside the replica of Mount Popa, a holy mountain in Myanmar’s dry zone. No “knowledge” can be gained from the various sites; even “edutainment” would be a stretch. Here as well, the number of visitors is minuscule, and it is not clear how profit ever could have been made. As a result, the whole site shows signs of decay and dilapidation, and many sites within were simply closed. Some were not, though.

Driving to the “Yangon” of the park, we found a (not too faithful) replica of Yangon City Hall, very much a building on an awkward scale, as the parked car illustrates. Inside, we discovered that the site had been leased to a well-known company that was operating an air rifle shooting range within.

To say that the message was mixed is not even correct. This specific usage was the result of arbitrary, unplanned action in the service of capitalist interest (even in the face of dismal revenue), untypical for our experience of Naypyitaw but possibly a sign of the normal breaking through into the utopian, as a planned city slowly becomes inhabited: a wedding held on the day of our visit by locals at a peripheral compound within the park, or the roadside noodle stall set up next to a proper but nonoperational restaurant.

Couple celebrating their wedding in the National Landmarks Garden with a replica of themselves (Photo: Judith Beyer/Felix Girke 2016)

Miniaturization found its pinnacle in the replica of Naypyitaw Exhibition Hall. Located within the Myanmar-shaped park just where Naypyitaw would be located on an actual map, this hall housed in its entirety an enormous diorama of Naypyitaw—including the National Landmark Garden itself. One of the few landmarks from the actual garden that found their way onto this map of the garden was the Naypyitaw Exhibition Hall that housed the very diorama.

Models all the way to the bottom: The Landmarks Garden next to the Defense Services Museum (Photo: Judith Beyer/Felix Girke 2016)

This collapse of the national territory into an inhabitable map of that territory inside the territory’s capital that in turn contained a map of the territory inside a representation of that capital that (finally) contains the representation of the capital itself is … bewildering to say the least. All this miniaturizing, this modeling of models, this condensing of a whole country into a park speaks of a limitless technocratic and possibly autocratic confidence in planning and infrastructure. Scale and size, clearly, were never daunting to the designers of Naypyitaw. Instead, they felt in total control over them.

Many who have written about Naypyitaw noted a lack of people—and indeed, the number of 1.15 million inhabitants for 4,800 square kilometers is strikingly low in comparison with other Asian capitals. The Facebook group “Humans of Naypyidaw” aims to help out by providing “refreshing insights”—pictures from the capital with short captions, showing that, indeed, there are already now all sorts of “Naypyidawrians”. Moreover, even the top-down design of Naypyitaw will not prevent encroachment by a disorderly population. There might be only few tourists, elderly, children, petty traders, artists, honeymooners, squatters, activists, or expat (I)NGO workers as of now. But once they trickle in, as they will, make their homes and use the infrastructure that is waiting for them, the purity and sobriety might give way to urban normalcy, and the excess of space will be tempered.

Judith Beyer is Junior professor of Political Anthropology at the University of Konstanz in Germany. She is specialized in legal and political anthropology and has worked extensively on Central Asia before establishing a second field site in Myanmar. Her most recent book, The force of custom: Law and the ordering of everyday life in Kyrgyzstan, is forthcoming with the University of Pittsburgh Press. In Myanmar, she works on land and property issues of non-Buddhist religious communities in the historical downtown area of Yangon.

Felix Girke is a research fellow at the Exzellenzcluster 16 “Kulturelle Grundlagen von Integration” at the University of Konstanz. His earlier work in southern Ethiopia focused on ethnicity, conflict, and identity politics. In his postdoctoral research, he investigates the politics of cultural heritage in Myanmar. The ongoing projects of both Beyer and Girke are situated in the contemporary climate of “change” that encompasses political, economic, and social transformations on all levels of society.

All pictures in this post are credited to the authors.

References

Gärtner, Uta. 2011. Nay Pyi Taw: The reality and myths of capitals in Burma. In Volker Grabowsky, ed., Southeast Asian historiography: Unravelling the myths. Bangkok: River Books Press.

Schatz, Edward. 2003. When capital cities move: The political geography of nation and state building. Kellogg Institute Working Paper 303.

Selth, Andrew. 2008. Burma and the threat of invasion: Regime fantasy or strategic reality? Regional Outlook Paper No. 17, Griffith Asia Institute.

Cite as: Beyer, Judith, and Felix Girke. 2016. “Naypyitaw: Rescaling materiality, capitalizing space.” FocaalBlog, 24 March. www.focaalblog.com/2016/03/24/judith-beyer-felix-girke-naypyitaw-rescaling-materiality-capitalizing-space.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.