The planning of fieldwork in anthropology is always shaped by a combination of expectation, uncertainty, and adventure. Before I began my own fieldwork in Barcelona in 2013, I imagined it as a kind of organic process in which my relationship with the participants would flow through the application of particular methods. This idea made me think initially that the filming of a collaborative documentary would be the perfect means through which to explore the relationship between graffiti and the use of public space in Barcelona. Then this idea was transformed throughout my research into a changeable process shaped by my everyday life in the city. In this setting, I applied visual methods within different contexts such as collaborations with artists and collectives, walking routes, exhibitions, and alternative TV channels. This allowed me to get involved in multiple ways of making graffiti and to produce videos about them. I edited together this visual material together using the Korsakow software, and it was presented as the visual practice project for my PhD thesis in Social Anthropology with Visual Media at the University of Manchester. The result is an interactive film called “Walking in Barcelona,” which allows the viewer an exploration of the mutable and diverse nature of the city looking at the relations between surfaces, places, and people. Here I want to reflect on these experiences and on the application of audiovisual methods within them.

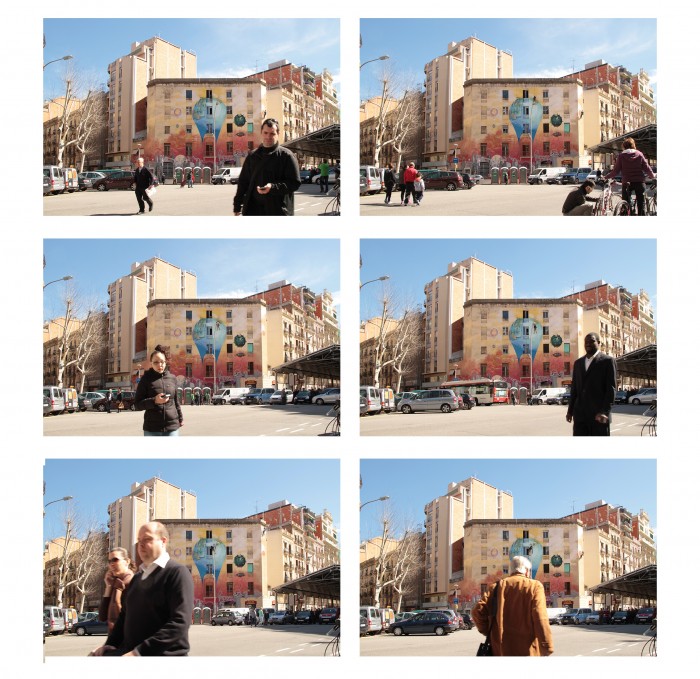

Throughout this process, I realized that if my aim was to engage in an anthropology “in” the city rather than an anthropology “of” the city (Low 1996: 384), I would have to focus on how the city was lived and embodied by its inhabitants, particularly graffiti and street artists but also me. This made me keen to develop a methodology in which I could adapt the use of visual media to the changeable and heterogeneous nature of the city and deal with its unpredictable circumstances. Thus, my fieldwork in Barcelona became not only a source of data and audiovisual material but also an experimental field for different practices, collaborations, and ways of representation. This led me to develop an ethnography of encounters, perceptions, and sensibilities linked to the conception of graffiti and street art as “textures” of the city, which stimulate the mind, body, and senses of its inhabitants.

One of the main objectives of my research was to access the visual culture of the public space in Barcelona as a broad field of critical practice, shaped by not only material elements but also everyday ways of seeing. W.J.T. Mitchell defines everyday seeing as “vernacular visuality,” which implies the study of both the social construction of vision and the visual construction of the social (2002: 170). Therefore, visuality is not limited to the sense of sight and linked only to a particular spatiotemporal way of seeing. Rather, it is a contested arena of multisensory experiences and heterogeneous ways of seeing linked to individual and collective practices. In this sense, “Walking in Barcelona” encloses working with surfaces and temporalities and within different social networks as part of an investigation into graffiti and public space. In this visual piece, the viewer can move between entering into the deep space of the screen through the central narrative and being on the surface of it making connections between multiple narratives. This does not imply that there are principal and subordinated narratives in this work but that they form part of a multidimensional reality. Here I was interested in articulating these dimensions and making a visual map based on the interfaces between paths, experiences, objects, and social relations.

My experience as an ethnographer was used as a method to embody the sensory dimension of what others might experience to produce academic knowledge and visual material (Hockey 2006; Pink 2009; Russell 1999). These ethnographic experiences took place in three situations that sometimes overlapped with each other and in which I adopted different roles as an ethnographer: as an observer, a collaborator, and a producer of images and sound. Thus, I interacted and engaged in dialogue with graffiti artists in the art center of La Escocesa, sharing and contrasting views about the public space in Barcelona and the practice of graffiti and street art over time. In addition, I also had the opportunity to observe and film how they worked in their studios, organized a graffiti mural festival in the center, and painted the outside walls as part of it. These were dialogues that mediated social relations through not only talking but also graffiti actions. In terms of my way of filming, I applied observational techniques to film the painting of large-scale murals on the walls of La Escocesa. This allowed me to capture the surfaces of the art center close up and look at the different interactions around them.

Applying a phenomenological model, the experiences of the everyday activities of the streets have been conceptualized by many academics as multisensory and not dominated or reduced to the visual sense as merely the operation of sight. I followed the approach to vision of Cristina Grasseni “not as a disembodied ‘overview’ from nowhere, but as a capacity to look in a certain way as a result of training the body” (2004: 41). Thus, the knowledge linked to graffiti and street art is not only produced by visual language but also embodied through the involvement of other senses, and of the practice of body movements as part of the understanding of the city. In “Making the Street,” I collaborated with the photographer Teo Vazquez and followed how his photographs went through different processes of transformation from the printer to the locations in the city space and from a conventional photograph to a street artwork. These transformations were inserted into the public space through my collaboration and embodied participation. The experience of these transformations and the existence of these images in the city were recorded in interviews, video recordings, and soundscapes. This information was later edited in a video, which formed part of the exhibition of Teo’s project at the art gallery La Escalera de Incendios and is included in “Walking in Barcelona.” The video represented the process of image making in connection with our journey in the city as a dynamic and juxtaposed dimension to the static nature of the photographs. The project gave me the opportunity to examine my position as both an anthropologist and a subject in my own research.

Graffiti murals are not only isolated images; they also form part of the fluidity of the city. I argue that the urban space is shaped by the movement of bodies within it, which creates a sense of plurality. Vanessa Chang (2013) has defined this as “embodied multiplicity,” and I have explored this idea within different contexts such as the painting of a collective mural in the squatted building of La Carboneria. My participation in the collective mural arose from my collaboration with “Grafforum,” a section of a TV hip-hop program focused on graffiti that was part of an alternative local TV channel broadcast on the local TDT called “La Tele.” It allowed me to get into contact with members of the local graffiti and street art scene and record and edit videos about their work. One of those encounters was with the squatter collective of La Carbonería, whose headquarters was in a squatted building in the center of the city. They got in contact with “Grafforum” for the “covering” (filming and dissemination) of the painting process of a new mural on the façade of their building. One of my aims was to capture the temporal transformation of the public space through the creation of the mural, and for this I made a series of time-lapse films. In the same way that the camera could not focus on all of the social events and material objects that occurred around it, the outcomes of the time-lapses shaped new ways of seeing the mural that had escaped my perception during the making process. The images coexisted in the same space but in different temporalities or what Bergson calls “durées.” This idea posits looking at these images according to “intuitive” insights as part of multiple presents with different, multiple pasts (Bergson in Mullarkey and Mille 2013: 1). They were part of my fieldwork and memories, but they also enclose information that reflects on public space and the use of the camera and my role as an anthropologist throughout this process.

Drawing an analogy between Situationist theories and graffiti and street artists’ interventions was useful to explore methodologies to experience and represent the city. Situationist International was a multidisciplinary group of revolutionary artists and theorists formed in the 1950s and 1960s, which sought to change the everyday life of ordinary citizens into a world of experiment, anarchy, and play (Sadler 1998:76). I put into practice some of the Situationist methods to experience and represent the city, such as the “derive,” the “détournement,” and the “psychogeography” analysis. Here, my body became a means to explore the city space, the graffiti practice, and how both are embedded in the everyday life of Barcelona. Thus, I walked in a “derive” mode through different neighborhoods of the city, taking notes of the contrast in street moods, different illuminations and people, and looking for graffiti and street artworks. Later, this information was used to create my questions in the dialogues with the graffiti artists. I walked routes with my participants or just by myself using my video camera to record them. I also used the method of “détournement” in my collaboration with Teo, transforming conventional photographs into street artworks and then street artwork images into anthropological knowledge.

Finally, in the visual presentation of this ethnography, I reassembled the graffiti and street art images that I produced as part of the short videos, time-lapse, sound recording, and photographs. In this way, I incorporated into my own research not only the artworks of the street artists but also an alternative cartography of the city produced by my own interaction with the city space. Throughout this process, the visual material of the street artworks was transformed into recorded anthropological visual materials. This allowed me to reconfigure and decontextualize the graffiti and street artworks to foster a communicative encounter between different viewing subjects. This methodology was based on the exploration of different forms of representation and an interaction with the space and was inspired by the strategies used by the artists with whom I collaborated in my fieldwork. The result is a compilation of visual material that, as I said in the introduction to this text, I have edited together to create this interactive video called “Walking in Barcelona.”

Plácido Muñoz Morán has recently completed a PhD in Social Anthropology with Visual Media at the University of Manchester (UK). He has special interest in the study of visuality, social movements, artistic practices, and the city with particular reference to participatory and collaborative anthropology research and the use of audiovisual means.

All photos in this post are credited to the author.

References

Chang, Vanessa. 2013. Animating the city: Street art, Blu and the poetics of visual encounter. Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal 8: 215–233.

Grasseni, Cristina. 2004. Skilled vision: An apprenticeship in breeding aesthetics. European Association of Social Anthropologists 12(1): 41–55.

Hockey, John. 2006. Sensing the run: The senses and distance running. Senses and Society 1(2): 183–201.

Low, Setha M. 1996. The anthropology of cities: Imagining and theorizing the city. Annual Review Anthropology 25: 383–409.

Mitchell, W.J.T. 2002. Showing seeing: A critique of visual culture. Journal of Visual Culture 1(2): 165–181.

Mullarkey, John, and Charlotte de Mille, eds. 2013. Bergson and the art of immanence: Painting, photography film. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Pink, Sarah. 2009. Doing sensory ethnography. London: Sage.

Russell, Catherine. 1999. Experimental ethnography: The work of film in the age of video. London: Duke University Press.

Sadler, Simon. 1998. The Situationist city. London: The MIT Press.

Cite as: Muñoz Morán, Plácido. 2016. “Writing on ‘Walking in Barcelona.'” FocaalBlog, 11 February. www.focaalblog.com/2016/02/11/placido-munoz-moran-writing-on-walking-in-barcelona.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.