This post is also part of a series on migration and the refugee crisis moderated and edited by Prem Kumar Rajaram (Central European University).

I visited Lampedusa from 24 September to 5 October 2015 to commence fieldwork research for my new project, Human Dignity and Biophysical Violence: Migrant Deaths across the Mediterranean Sea. This photo essay documents some of the key encounters that I experienced during my visit.

I want to stress here that I originally had no intention of collecting images for a photo essay as part of this trip. I spontaneously took the photos on my mobile phone, and there is much room for improvement in terms of technical and compositional quality. Moreover, my compilation of these images into an essay is far from how I might have chosen if I had planned to produce a photo essay from the start. Despite its various limitations, I nevertheless hope that the essay is of value.

So, what can a photo essay offer in the context of a relatively short research visit to Lampedusa, and what are the perils of such an approach in documenting a particular place at a particular moment in time? I have found this photo essay invaluable in helping me to work toward creating what Alan Latham refers to as a “more supple and pluralistic” account of the social events that I want to describe (Latham 2003: 2003). Rather than presenting a smooth academic narrative based on an overarching interpretation of Lampedusa at a particular moment in time, the photo essay enables me to document and reflect upon the diverse and incongruous realities that I encountered in a relatively small space and a relatively short period of time. As is evident in the essay itself, these encounters occurred due to the intensification of border and migratory politics at the time of my visit from late September to early October 2015.

In her pioneering work on critical visual methodologies, Gillian Rose (2012) emphasizes the importance of paying attention to the social conditions within which images are produced. Crucial here is to emphasize the relatively large number of journalists, artists, and researchers I met during my visit, as well as in the notable presence of various military agencies and NGOs on the island. Even though Greek islands such as Lesbos have emerged as key sites of border and migratory politics during the spring and summer of 2015, Lampedusa still occupies an important space in contemporary European border and migratory imaginaries. This is indicative of Lampedusa’s continued significance as a site symbolic of the EU’s security and humanitarian border regime (Cuttitta 2014).

One of the distortions that this symbolic investment in Lampedusa provokes is a contrast between the hyper-invisibility of some issues and voices over others. For example, many local residents are silenced by the presence of journalists on the island. As a researcher, I also experienced this silence—even with good friends who were sometimes hesitant or reticent in discussing an issue that has dominated the island’s media image for many years. This often reflected a concern about the impact of migration on the island’s tourist industry, which in turn means that migrants who arrive are removed from sight and contained within the detention center. Although I witnessed two arrivals during daylight on my visit, local activists told me that arrivals usually happen at night to try to prevent the dominance of migratory images in the press. While locals see migration as having been overrepresented as an issue in the Lampedusan context, it therefore seems that efforts to rectify this have created the conditions for a further silencing of migrants.

In this context, a photo essay has significant potential in countering the hyper-visibility and audibility of some issues and voices over the invisibility and inaudibility of others. Particularly important here is that the photo essay presents a wider range of images alongside those that are more familiar in mainstream media. Nevertheless, the essay is far from ideal as a critical intervention. Migrants only appear in these images from afar. Notable to me, but not to the audience, is that the direct and more sustained encounters and dialogues that I had with diverse migrants during my visit are completely absent from the photo essay. Not taking photos of people in this regard is largely purposeful, in order to avoid the risk of identification. Nevertheless, in terms of the finished product of a photo essay, this potentially leads to the undesirable effect of provoking existing dynamics of visibility and invisibility. Taking seriously Rose’s call to “take images seriously,” there are therefore many problems here that make the perils of a photo essay only too evident.

Nevertheless, I do still publish the photo essay—albeit with a cautionary note. I do so with the hope of partially destabilizing what Rose calls familiar “scopic regimes.” The techniques I use here are threefold. First, I use juxtaposition in an attempt to highlight Lampedusa’s multiple realities and incongruous dynamics. Second, I emphasize lines of conflict or tension in order to pay attention to highlight some of the political stakes arising in this context. Third, I weave lone voices into the essay to prompt reflection on how interventions into Lampedusa’s migratory politics involve relations of power, privilege, and violence. Of course, I do not necessarily succeed in this endeavor, and the peril remains that this is a photo essay that contributes to, rather than challenging, established ways of viewing Lampedusa and its migratory politics. Nevertheless, I hope at least that the essay invites reflection and reflexivity for the viewer, as it has for me in the process of its creation.

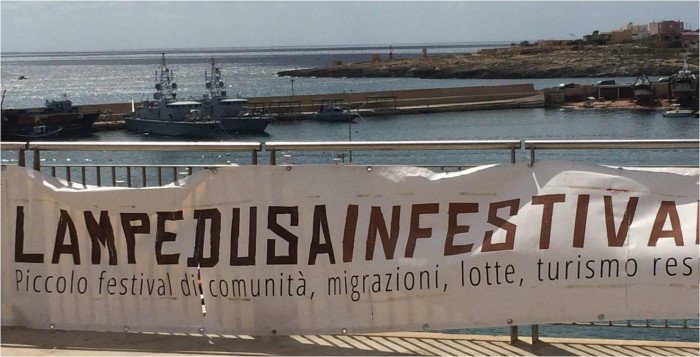

23–26 Settembre 2015

“LampedusaInFestival: a small festival of community, migration, struggles, responsible tourism.” With Lampedusa, a symbolic place at the “edge” of Europe, this festival brings together activists from key migration “flashpoints,” including Calais, Melilla, and Ventimiglia. Together, yet not without some disagreements, the wider collective take steps to create a political vision and network, as well as to engage in direct action and cultural activities, and to share various mediatized interventions produced by activists across Europe.

PortoM, casa Askavusa

The “barefoot” collective was formed in 2009 based on the “passion and desire of young people of Lampedusa” to address migration. The frontage of PortoM overlooks the sea and was made from the remains of migrant boats by a local craftsman and previous member of the collective. Askavusa is opposed to militarization and dedicated to analysis and interventions that can transform not only the situation in Lampedusa but also the “system” that has created the migrant emergency across Europe.

Capitaneria di Porto Lampedusa, vicini di casa di PortoM

Neighboring Askavusa’s PortoM center is the Guardia Costiera port harbor office. Several Guardia Costiera boats are lined up in the harbor in front of the building, marked by the characteristic Charlie Papa “coming to get you” identification numbers—CP320, CP302, CP312, CP324, etc. Guardia Costiera plays a prominent role in search and rescue (SAR) activities in the region. This is the authority that was called to the scene of the notorious 3 October 2013 shipwreck, in which 368 people died just off the shores of Lampedusa.

Radar anti-migranti

The military are a strong presence on the island, with various bases in its more remote areas. Notable among these is a former United States army base, LORAN, which has since been closed and the infrastructure dismantled. This is also the site where migrants were held in 2011, when the island faced increased arrivals following the Arab Spring uprisings. The “anti-migrant radar” shown in this image is one of many on the island. The electromagnetic rays have been the subject of several recent investigations and are a growing health concern for many local Lampedusans.

“Bella Ciao”

On 25 September, activists from across Europe visit the Lampedusa migrant reception center to stage a protest. Some activists call out to those contained within the center, shouting “freedom, sisters” or asking about conditions in the center. Holding a banner “No war – No hotspots,” activists sing the antifascist resistance movement song “Bella Ciao” with a guitar accompaniment. In response, many of the migrants in the center wave, watch, and clap to the music. Another calls out, “So what can you do to help us?”

MS Sea-Watch, Germania

The “private pleasure boat” Sea-Watch returns after its final journey of 2015 patrolling the SAR zone. While conceived as an “eye” in the sea that looks for migrant boats in distress, it has in effect become part of a wider network of SAR operations in its own right. Sea-Watch is a private initiative set up by a group of friends in Germany. The aim of the project is “to challenge the unbearable circumstances” in the Mediterranean Sea, using “a practical approach” in order to put pressure on official authorities to fulfill their duty to respond to a vessel in distress.

Le motovedette della Guardia di Finanza

Between 10 a.m. and midday on 28 September, approximately 220 people disembark from two Guardia di Finanza boats at the secure military harbor in Lampedusa. They are met by a range of authorities and NGOs, as well as by solidarity activists who have been given authorization to hand out tea and biscuits. Information circulated among activists before the arrival suggested that the people arriving were all women and children. Other than just a few women and children, all those disembarking are in fact men.

L’autobus delle Misericordie

Confederazione Nazionale delle Misericordie d’Italia is a nationwide confederation of brotherhoods that is defined as showing mercy to the “needy.” It also operates in various welfare centers and currently holds the lucrative contract for running the migrant reception center in Lampedusa. The yellow and blue uniforms of Misericordia workers are visible throughout the town of Lampedusa, accumulating in the Catholic Church of Parrocchia San Gerlando. In this image, the Misericordie bus transports new arrivals from the port to the center.

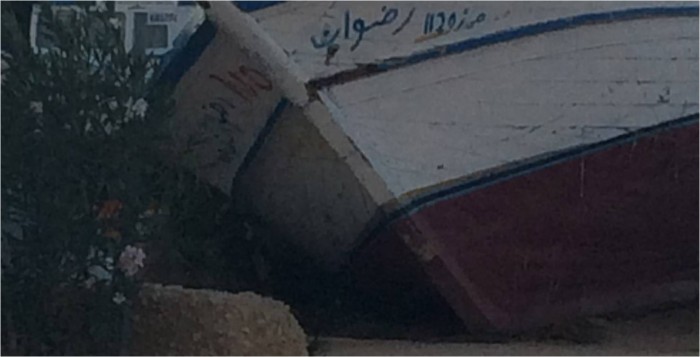

Il Cimitero delle Barche

The migrant boat cemetery overlooks the new harbor, next to the football pitch where children play. At times in the past, the boat cemetery could not be entered and was guarded by the military to prevent people from accessing the site. Yet, as with the current migrant center, activists could nevertheless find access to view the boats from around the back, and the site has since been opened for free access. Until November 2014, the large field was full of boats, though almost all have since been broken up and removed. The remaining few have graffiti added to the boat name markings. This reads, in red, “No.”

Il cimitero umano

Migrants are often buried several to a grave in Lampedusa’s cemetery. These two graves each hold two men, none of whom are named. They are described as most likely from the Maghreb, two around 30 years old, and two around 35 years old. The migrant graves sit next to a well-tended grave of a 7-month-old baby from Lampedusa, with flowers, pictures, and, of course, the baby’s name, date of birth, and date of death recorded on the headstone. Maintenance is carried out by the cemetery while local activists have in some cases managed to identify those buried, adding names to the headstones in order to give migrants “dignity” in death.

Oggetti migrant

In PortoM, some of the migrant objects that Askavusa activists have collected since 2009 are on display. These are described as “vehicles of stories,” which highlight the shared histories of migrants and local people. Amid the exhibition there is an additional display created by a local resident. This includes thirty-five or so profile photos of unnamed people of different ages, genders, and ethnicities. Each photo is attached to one of four strings by a clothes peg and each person holds a number. The display challenges the observer, “Explain me the difference.”

Resti in barca

In November 2014, many of the boats in the cemetery were dismantled, the majority broken up and removed from the site. In an attempt to prevent everything from disappearing, local activists retrieved what they could from the site. These are now found in different places across the island. Those from this picture are located in the plot of a local shipbuilder and carpenter, who also has various migrant belongings stored on the site. “What will you do with them?” I ask. He tells me that he does not plan to do anything with either the boat remains or belongings, and simply keeps these as a mark of respect.

Il traghetto Siremar

On 1 October, the first European “hotspot” formally opened in Lampedusa. The next day, migrants protest at the center with signs and chants against being imprisoned and fingerprinted. Soon after, many queue up to depart on the 10:45 a.m. Siremar Ferry to Porto Empedocle in Agrigento. Once the other passengers are on the upper decks, they file on one by one with identical matching bags on their backs and are handed large bottles of water by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Two late arrivals nearly miss the boat and are escorted past passengers and into the enclosed room for migrants, where they remain throughout the journey.

Santuario delle tartarughe

The turtle sanctuary is located directly opposite the Siremar Ferry terminal. This is a hub for volunteers, as well as for tourists who come to see the injured turtles that have been rescued when caught in the hooks of local fishermen. In 2011, larger groups of people began arriving on the island following the Arab Spring uprisings, and approximately six hundred people were living among the turtles in the center. “Look how small the space is for the turtle’s brain,” the founder and director of the project points out on a turtle skeleton. “Still, we have a lot to learn from the turtle: that there are no frontiers and the sea is for us all.”

Comitato Tre Ottobre

3 October has become a memorial day for the shipwreck that occurred in 2013 near to the island of Lampedusa. On 3 October 2014, there was an official memorial with survivors and high-level politicians from both Italy and the EU. One year on, it is perhaps a slightly less spectacular affair, held over three days and involving workshops for children, various cultural installations, and an official commemoration event. In this image, some of the survivors of the shipwreck attending the event hold a quiet remembrance at memorial gardens overlooking the sea.

Torn

A UNHCR-commissioned documentary shot about refugee artists in Lebanon and Jordan, Torn, is shown in the large square in front of the Catholic Church of Parrocchia San Gerlando. It is one of the events organized by the Committee of 3 October, which is widely supported by local, national, and international groups and organizations. Askavusa activists circle the crowd dwarfed by the large square, handing out flyers for a counter-film that highlights local protests and the delayed coastguard response on 3 October 2013. This is shown two blocks up the road the following evening, where a large crowd dominates a small square.

Una corona per la commemorazione

The official 3 October commemoration begins at 10 a.m. with perhaps 250-plus children gathering for a street march to attend the formal ceremony led by the Nobel Prize–nominated Eritrean priest, Padre Mussie Zerai. Following this, the survivors, along with a select group of officials and organizational representatives, board boats to attend a commemoration at sea. Observers aboard a Carabinieri boat trail the survivors and officials on board Guardia di Finanza and Guardia Costiera vessels. Out at sea, the survivors are involved in the placement of a wreath of white flowers in the water where the shipwreck of 2013 occurred.

Celebrate i morti

As survivors board the boats for the commemoration, members of the Askavusa collective demonstrate outside the turtle sanctuary with a banner: “No war – No hotspots * Celebrate i morti ammazzate i vivi * No war.” As the survivors and others arrive to board the boats, activists call out, “They are lying to you!” and “Don’t trust the police!” Since access to the boarding area is secured, people who have made friends with the survivors during their time on the island watch the proceedings from behind metal fencing. As they wave to the survivors, some call back expressing thanks to those attending.

Memoria tra mare e cielo

Following the official memorial events, an alternative interfaith ceremony “between sea and sky” is organized by the Italian Evangelist Church group Mediterranean Hope at the Santuario della Madonna di Porto Salvo. “Words and gestures of faith” are shared in this ceremony in order to remember the victims of the 3 October 2013 tragedy. Various people speak at the ceremony, including a spokesperson for the attending survivors of 3 October. Music is played and prayers are led by Mussie Zerai and others, with various religious leaders from Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States present.

La Spiaggia dei Conigli

Rabbit Beach was voted the world’s best beach in 2013 by a well-known travel website. It remains a popular tourist destination, with the water both warm and clear for many months of the year. Despite this, locals are concerned with the wider impact of media representations about migration to the island. With no hospital and limited state-provided services for the local population, the island depends heavily on the tourist industry. I finally visit the beach to please the lady in my guesthouse (“Rabbit Beach, have you been to Rabbit Beach?!”). As I leave in the evening, a helicopter circles overhead.

I migranti dalla Tunisia

At around 6 p.m. on 4 October, the route back from the beach is deadlocked, with people rushing to follow the helicopter-monitored arrival of Tunisian migrants with their cameras and phones. Around twenty to thirty people, men, disembark from the Guardia Costiera vessel that they arrive on, and are removed from the military harbor on the Misericordie bus with a police escort. The disembarkation is less prepared and much quicker than the previous arrival on 28 September, and I later hear that the Tunisian migrants made it nearly all the way by boat before calling out in distress.

This photo essay forms part of the research fellowship Human Dignity and Biophysical Violence, funded by the Leverhulme Foundation. Thanks are extended to Cita Wetterich and Simona Bonardi, as well as to all those supporting my fieldwork for this project. All photos are credited to the author.

Dr. Vicki Squire is Associate Professor of International Security at the Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Warwick. She is author of The Exclusionary Politics of Asylum (2009), The Contested Politics of Mobility (2011), and Post/Humanitarian Border Politics Between Mexico and the US: People, Places, Things (2015). Dr Squire is currently Leverhulme Research Fellow on the project Human Dignity and Biophysical Violence: Migrant Deaths across the Mediterranean Sea, as well as PI on the ESRC project Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat.

References

Cuttitta, Paolo. 2014. “Borderizing” the island: Setting and narrative of the Lampedusa “border play.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 13(2): 196–219.

Latham, Alan. 2003. Research, performance, and doing human geography: Some reflections on the diary-photograph, diary-interview method. Environment and Planning , 35: 1993–2007.

Rose, Gillian. 2012. Visual methodologies. London: Sage.

Cite as: Squire, Vicki. 2016. “12 days in Lampedusa: The potential and perils of a photo essay.” FocaalBlog, 11 January. www.focaalblog.com/2016/01/11/vicki-squire-12-days-in-lampedusa-the-potential-and-perils-of-a-photo-essay.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.