From politics of culture to politics of justice

Nepal promulgated its constitution on 20 September—the first after ending the monarchy, and one replacing the interim constitution in place since 2007. That interim constitution had been put in place to mark the peace agreement with the Nepali Maoists, mainstreaming them into democratic politics and unarming them under the UN mediation. While there were other obstacles in finalizing the constitution, the hardest nut to crack has been the issue of federalism because it involved finding a way to work Nepal’s multiple ethnic and regional identities into the mono-ethnic nationalism institutionalized by the state thus far.

There are more than a hundred ethnic groups in Nepal scattered in its diverse terrain ranging from the Himalayas in the north to the Tarai/Madhesh flatlands of the south. The caste hill Hindu elite (CHHE), comprised mostly of Bahuns and Chhetris, rose to power after Prithvi Narayan Shah, a Chhetri king, conquered numerous small kingdoms to form the modern state of Nepal in 1769, and they remained privileged even after Nepal became democratic in 1990. The indigenous nationalities from the hills (Janajatis), Hindu low castes (Dalits), and flatland dwellers (Madheshis) remained marginalized in all spheres of public life. The Nepali Maoists targeted ethnic exploitation during their People’s War between 1996 and 2006 and were the first to demand a new constitution.

Mass meeting of the Tharu people in the far western Tarai town of Tikapur (Photo: Krishna Kumar Chaudhary)

In this post, I briefly summarize the constitutional negotiations spanning nine years, showing that ethnicity and exploitation took center stage, which, in the second part, informs a review of anthropologists’ take on the Maoists and ethnic politics in Nepal.

Nine years, two assemblies, and one constitution

The first Constituent Assembly began its term exuberantly in 2008. Its first act was to officially dethrone Hindu King Gyanendra, who had assumed power in 2001 after the royal family was allegedly massacred by the crown prince, who later shot himself dead. Initially a constitutional monarch, like his slain brother, King Birendra, Gyanendra committed a coup d’état of sorts, trying to sideline all political parties based on what he said was an urgent need to clamp down on Maoist guerillas. This failed in 2006 not least because the parties, especially the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist–Leninist)—referred jointly as NC–UML hereafter—instead joined hands with the Maoists to secure a comprehensive peace agreement and end a decadelong People’s War.

However, as they sat down to write the constitution, disagreements surfaced. The Maoists and Madheshis, significantly large in number in the first Assembly, wanted ethnic grievances about persistent historical inequalities to be addressed and overcome by way of federalization and affirmative action. The NC–UML instead argued that federalization, if done, should be based on economic viability. Multiple maps with varying numbers of federal states and how these should be delineated floated in the Assembly, and expert committees were commissioned to advise on technical matters. Although the Maoists and Madheshis could have secured a majority at this time, all parties agreed that a constitution should be promulgated only through consensus (sarvasammati) and not majority (bahumat). Unfortunately, however, a consensus could not be reached, and after the Supreme Court ruled against extending its term, the Assembly formally disbanded at midnight on 28 May 2012.

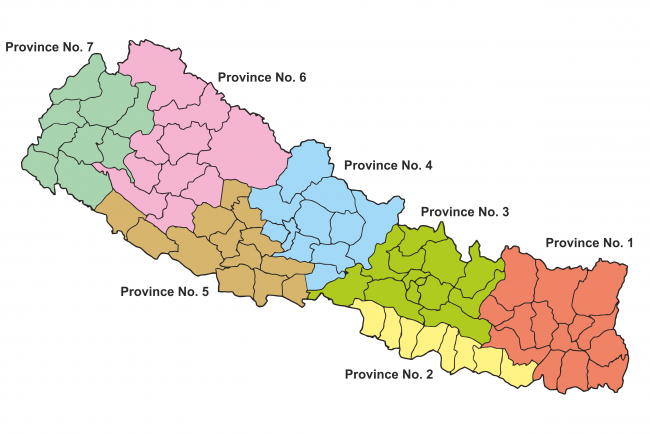

Provinces of Nepal according to the Schedule 4 to the Constitution of Nepal, 2015 (Photo: Aotearoa via Wikimedia Commons)

The second Constituent Assembly, emerging from general elections in 2013, had a different composition. The federalist forces (i.e., the Maoists and Madheshis) secured many fewer seats while the old parties NC–UML won the majority. The Assembly remained caught in a deadlock even as the opposition intensified protests to ensure that the state stayed committed to federalism and that ethnic grievances were addressed. An attempt to override the earlier understanding on sarvasammati to “fast-track” the constitution-writing process through bahumat backfired on NC–UML forces when the Maoists and Madheshis physically barred the constitution document from reaching the speaker of the Assembly by encircling (gherao) the rostrum.

Three months after failed attempts at fast-tracking, Nepal was hit with a devastating earthquake on 25 April 2015. With more than 9,000 deaths and 22,000 injured, the country united in grief. Capitalizing on this fleeting moment of national unity, the three largest parties in the Constituent Assembly—NC–UML and the Maoists—but also one of the many factions among the Madheshi parties seized a “16-point deal” to pass the constitution through the Assembly. Even though the only Madheshi faction walked out because the federal map that emerged from this deal overlooked its concerns, the “big three” still went ahead amid wide protests in the southern flatlands of Tarai/Madhesh.

That the battle on federalism was so acrimonious in terms of ethnic and regional divisions of power shows the centrality of ethnicity and its political representation in Nepal’s ongoing transformation. This is what prompts me to review how anthropologists have problematized ethnicity and identity in Nepal, especially in the context of the People’s War led by the Maoists that lasted a decade. Below, I show how this focus and its very particular understanding of how to research a “people’s war” now almost overshadows all other ways of understanding the Maoist movement and its aftermath. I offer some preliminary reflections how our research focus and questions may be adjusted.

A Madheshi student leader in a mass meeting in Delhi protesting human rights abuse in Nepal (Photo: Mallika Shakya)

An anthropology of the People’s War

Anthropologists have been reluctant to problematize the ethnic realpolitik at play in their field sites. Among the first to produce ethnographies of villages under Maoist influence was Anne de Sales (2000), who argued that the Magar Janajatis from the Maoist heartland in Rolpa were “cleverly” exploited by the Maoists to protest state indifference to their isolation. Judith Pettigrew (2004) argued that young people in Maurigaon joined the guerilla rather as a rite of passage toward “modernity” than as an act of political conscience. Much of the early anthropological literature went on to portray the Maoists as crude rebels piggybacking on cultural idioms to sell communist jargon while the villagers were depicted as innocent victims caught in the cross fire between the rebels and the state. The politics of the (guerilla) war itself formed just a backdrop in anthropological narratives, which were largely put together through secondary sources and not ethnography per se. Ethnographies of political institutions—Maoist and others—were rare. In other words, early ethnographies established few connections between the events in individual villages and a national phenomenon, which rested on an ideology speaking to broader issues and which had an apparatus similar to many revolutionary movements in the era of decolonization.

To better understand how anthropologists studying Nepal’s People’s War have dealt with the discipline’s more general and fairly existential problem of explaining the “part” while not losing sight of the “whole,” I will divide the corpus of anthropological writings on the People’s War into two approaches. The first focuses on the Maoist movement itself and explores the ideology and practice of Nepali Maoists as armed rebels. The second chiefly considers the everyday lives of ordinary people living in Maoist areas. The latter approach soon became dominant whereas the former remains a rarity.

Saubhagya Shah (2004) correctly identified that Nepali Maoists focused less on Mao’s economic and political programmatic while they offered greater clarity and commitment on proposals for ethno-religious and regional mobilization. Philippe Ramirez (2004) contextualized the Nepali Maoist movement with similar movements elsewhere in the world. Regrettably, this line of anthropological writing more or less disappeared after Shah died a few years later and Ramirez left Nepal to study northeast India.

The second group of writings has proven prolific. Almost all of the writings in this category took the position that the ethnic associations and their leaders “oscillated” between concerns that the Maoists were either “exploiting” ethnicity or could help realize greater equality among ethnic groups (Lecomte-Tilouine 2004: 129). Based on research in Nepal’s central hills, Shneiderman and Turin (2004: 103) argued that even if the Maoists were “quick to adopt” cultural means to spread their messages, they offered no reassurances toward ethnic autonomy or a federal state. The Maoists were portrayed as opportunists adopting the stylistics of Hindu life cycle rituals to articulate emancipatory class struggle but refraining from making any commitment on ethnic justice. In other words, anthropology contributed to a discourse portraying the Maoists as “outsiders” and knowledgeable exploiters of culture in pursuit of a crude party agenda promoting emancipatory class struggle (de Sales 2003). The central argument of Pettigrew’s (2004) “first hand” account of living conditions in insurgency-affected areas was that villagers negotiated the terms of Maoist intrusion into their intimate spaces (houses and courtyards) by invoking cultural protocol of hospitality.

Although more recent writings largely reproduced this second genre of anthropological approaches to the People’s War, there have been few exceptions. Sara Beth Shneiderman (2009) is probably among the few who confessed that the size of the Maoist rally in her field site made her rethink earlier claims, and she acknowledged that the persistence of ethnic exploitation and their campaign against this might have offered the Maoists a hegemonic device against state. Susan Hangen (2013: 124) further substantiated this hegemony argument in her study of ethnic interlocutors’ boycotting of a major Hindu festival, Dashain, in the eastern hills as a rebellious “mnemonic practice.” However, anthropologists who contributed to a volume edited by Marie Lecomte-Tilouine (2013) on the “revolution in Nepal” focus primarily on “tears” and what she called a “libidinal economy.”

In sum, it may be fair to say that accounts of the People’s War in Nepal have kept the wider, national, and ultimately decisive “politics” outside of their ethnographic gaze. Otherwise, such politics have been reduced without further questioning to “everyday politics”—to the extent that even ethnographies claiming to analyze terror and violence, jan sarkar (people’s government), and Maoist model villages have muted the realpolitik that would change Nepal’s constitution for good.

The case of the People’s War in Nepal and how this culminated in constitutional change and an end to royal rule then indicates how in anthropology it still seems possible to deny universalistic claims on modernity by way of localizing desire(s) for emancipation and denying the wider ambition of villagers to end conditions of terror. What a future research anthropological agenda on Nepal may want to illuminate is not the obvious fact that there are overlaps between party tactics and cultural-religious sentiments, but instead how the movement originated, gained momentum, and then transformed itself through a complex web of alliances and counter-alliances between political parties, cultural entities, and others. Such a reminder might be timely as Nepal is turning a new constitutional page to shed Hindu monarchy and embrace a multiethnic federal structure.

Editor’s note

For more on ethnicity and politics in Nepal from Focaal, see:

- Hirslund, Dan V. 2015. Militant collectivity: Building solidarities in the Maoist movement in Nepal. Focaal 72: 37–50.

- Hoffman, Michael. 2014. Red salute at work: Brick factory work in postconflict Kailali, western Nepal. Focaal 70: 67–80.

- Hoffman, Michael. 2014. “Strong vs. weak targets: Urban activist practices of the Kamaiya Movement in the western lowland of Nepal,” FocaalBlog, October 30.

- Shah, Alpa, and Sara Shneiderman. 2013. The practices, policies, and politics of transforming inequality in South Asia: ethnographies of affirmative action. Focaal 65: 3–12.

- Shneiderman, Sara. 2013. Developing a culture of marginality: Nepal’s current classificatory moment. Focaal 65: 42–55.

- Pfaff-Czarnecka, Joanna. 2011. No end to Nepal’s Maoist rebellion. Focaal 46: 158–168. — Free PDF download

Mallika Shakya works as Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at South Asian University in Delhi. She works on nationalism, development politics, industrialization, and trade union movements in Nepal, South Africa, and beyond. She has a PhD from the London School of Economics and was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford.

Follow Mallika on Twitter here.

References

de Sales, Anne. 2000. The Kham-Magar country, Nepal: Between ethnic claims and Maoism. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 19: 41–71.

de Sales, Anne. 2003. Remarks on revolutionary songs and iconography. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 24: 5–24.

Hangen, Susan. 2013. Boycotting Dasain: History, memory and ethnic politics in Nepal. In Mahendra Lawoti and Susan Hangen, eds., Nationalism and ethnic conflict in Nepal: Identities and mobilization after 1990, pp. 121–144. New York: Routledge.

Hutt, Michael, ed. 2004. Himalayan people’s war: Nepal’s Maoist rebellion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Lecomte-Tilouine, Marie. 2004. Ethnic demands within Maoism: Questions of Magar territorial autonomy, nationality and class. In Hutt, Himalayan people’s war, pp. 112–135.

Lecomte-Tilouine, Marie. 2013. Revolution in Nepal: An anthropological and historical approach to the people’s war. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Pettigrew, Judith. 2004. Living between the Maoists and the army in rural Nepal. In Hutt, Himalayan people’s war, pp. 261–284.

Ramirez, Philippe. 2004. Maoism in Nepal: Towards a comparative perspective. In Hutt, Himalayan people’s war, pp. 192–224.

Shah, Alpa, and Judith Pettigrew. 2009. Windows into a revolution: Ethnographies of Maoism in South Asia. Dialectical Anthropology 33(3): 225–251.

Shah, Saubhagya. 2004. A Himalayan red herring? Maoist revolution in the shadow of the legacy Raj. In Hutt, Himalayan people’s war, pp. 192–224.

Shneiderman, Sara Beth. 2009. The formation of political consciousness in rural Nepal. Dialectical Anthropology 33(3): 287–308.

Shneiderman, Sara Beth, and Mark Turin. 2004. The path to Jan Sarkar in Dolakha district: Towards an ethnography of the Maoist movement. In Hutt, Himalayan people’s war, pp. 79–111.

Cite as: Shakya, Mallika. 2015. “Ethnicity in Nepal’s new constitution: From politics of culture to politics of justice,” FocaalBlog, 28 September, www.focaalblog.com/2015/09/28/mallika-shakya-ethnicity-in-nepals-new-constitution.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.