To appreciate the role of aesthetics in politics, we might look to the recent resurgence of popular anti-corruption movements in India. In 2011 and 2012, mass protests by supporters of the India Against Corruption (IAC) movement focused around spectacular fasts by the social activist Anna Hazare. Hazare’s projection of moral authority draws upon a well-established Indian idiom of non-party “saintly politics” (Morris-Jones 1963). The ascetic aesthetic of this approach, in Hazare’s case, is projected through the adoption of simple, hand-woven khadi cotton clothes and practices of abstinence (Pinney 2014; Webb 2014). More recently, a new political formation, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), or the Common Man Party, headed by Hazare’s erstwhile IAC colleague Arvind Kejriwal has been promoting an ethical and anti-corruption alternative in electoral politics.

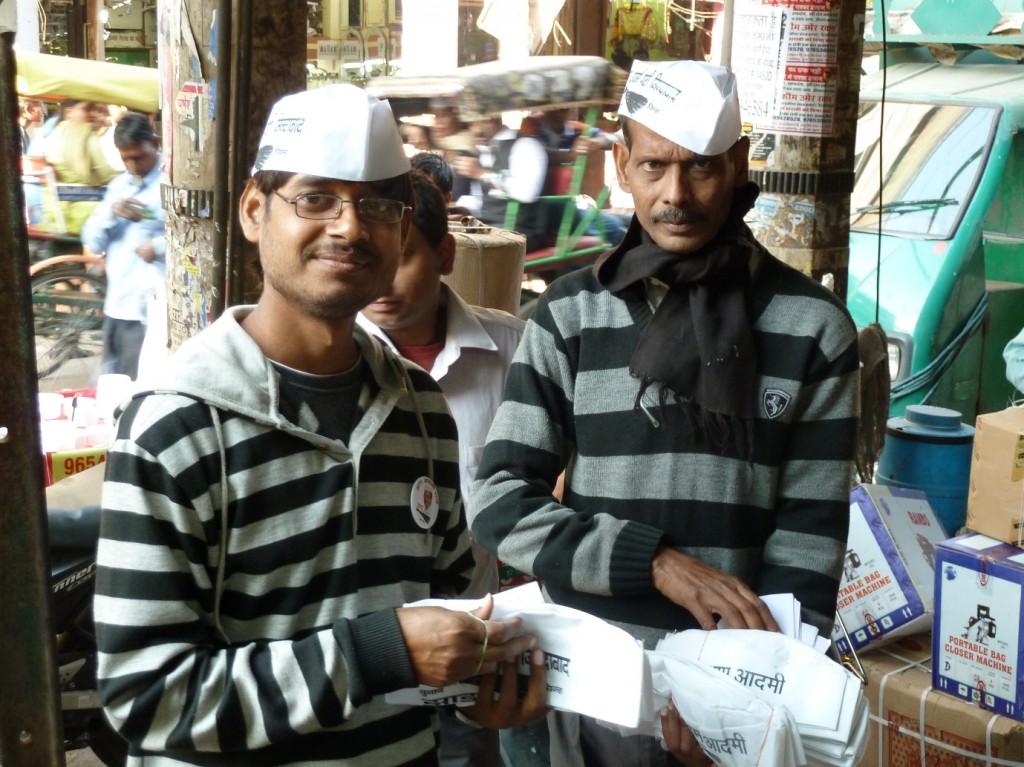

The movement has inspired large numbers of volunteer workers to take to the streets supporting electoral campaigns at the state and national level (Roy 2014). In February 2015, the AAP achieved a remarkable victory in the Delhi assembly elections, winning 67 seats out of 70. In both cases a simple white topi (cap) printed with slogans became the signature of the movements. The mass distribution of the caps provided opportunities for activist interventions into the flow of everyday life in the streets, a means through which people could easily demonstrate support. As an alternative to remote and overbearing campaign posters, the caps made the movements visible in public spaces by attaching a mobile symbol to individuals. This aesthetic tactic projected the movements as collections of active citizens able to contribute through their own agency. The adoption of the cap suggested the initiation of personal and national redemption.

Aam Aadmi Party volunteers wearing and distributing caps to the public in Chawri Bazaar, Delhi, 2013 (photo by Martin Webb)

Aam Aadmi Party volunteers wearing and distributing caps to the public in Chawri Bazaar, Delhi, 2013 (photo by Martin Webb)

The caps, cheaply produced, are ephemeral objects. They are made of the same recycled fabric that Delhi uses for its shopping bags. However, their style powerfully reiterates key moments of protest and struggle in the life of the Indian nation. In their design, the caps are an explicit reproduction of the “Gandhi topi,” a simple white cap of hand-woven khadi cotton worn by supporters of the pre-independence, non-cooperation movement as a sartorial intervention in the struggle against British occupation (see Tarlo 1991). Therefore, when a contemporary IAC or AAP activist states that India—with its resources, ingenuity, youth, and energy—has no need to struggle but rather that its natural advantages are stymied by corruption and crony capitalism, they may be making an argument echoing familiar discourses of good governance and state reform. However, when they do this wearing a white topi, which reiterates the political aesthetics of the independence struggle, they are making an explicit argument about the betrayal of a national project. Both IAC and AAP protestors have always been clear about this; their activism is part of a “second struggle for independence,” as stated simply in the painted sign held by an IAC protestor at India Gate, New Delhi, in 2011: “Kale Angrezo Bharat Choro” (Black Englishmen Quit India) (Pinney 2014: 186). The “black Englishmen” in this case are the politicians and bureaucrats that administrate the postcolonial nation.

The citation of the struggle for Indian independence does not stop at caps. A concatenation of national images, political icons, and historic slogans were linked and sustained across the IAC protests and AAP election campaigns. The call and response of historic chants at rallies—“Inquilab! Zindabad!” (Revolution! Live forever!)—blended with publicity material that juxtaposed images of movement leaders, iconic figures of the independence struggle such as M.K. Gandhi and Bhagat Singh, and recent martyrs to the anti-corruption cause (see Webb 2014; Moffat 2014).

“Kale Angrezo Bharat Choro” (Black Englishmen Quit India) – placard displayed at India Gate, Delhi, 2011 (photo by Christopher Pinney)

“Kale Angrezo Bharat Choro” (Black Englishmen Quit India) – placard displayed at India Gate, Delhi, 2011 (photo by Christopher Pinney)

The IAC and AAP caps, then, are examples of the ways the Indian political archive is, to use Christopher Pinney’s evocative phrase, “continually spewing the past into the future” (2014: 178), providing a resource of images, concepts, and actions that are dynamically folded back into protest spaces, media representations, and public culture. Setrag Manoukian (2011) has identified similar processes of citation in the 2009 Green Revolution uprisings in Iran, and building from these examples we can see how political archives act as vernaculars through which movements develop rhetoric and imagine social relations. As Manoukian points out, these vernaculars are not bounded; they draw on specific political histories but are mobile and given to hybridity. Protest movements exhibit a vernacular cosmopolitanism (Werbner et al. 2014), voraciously consuming and remaking new images by weaving in songs, stories, bodily gestures, and practices from other movements and histories. The rhythm of protestors chanting “ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam” (the people demand the fall of the regime) throughout the Arab Spring uprisings was echoed by protestors in Spain’s 15-M Movement, by the occupiers of Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv, and by those chanting “no ifs, no buts, no education cuts” in the United Kingdom (see Fred Cummins for more comparisons). Everyday practices of occupation and communication are cited and reiterated across protest sites in different countries: the tent encampments of the Occupy movement replicated in London, Tel Aviv, Madrid, Istanbul, and, most recently, Hong Kong; the wall of sticky notes famously deployed by protestors of Hong Kong’s 2014 Umbrella Movement (Cox 2014) echoing the intentionally ephemeral “analogue Twitter” of the 2011 Spanish 15-M occupations, in which supporters stuck notes to a pedestal in Barcelona’s Placa de Catalunya to convey messages to visitors to the protest camp (Postill 2014: 358).

Political aesthetics, then, can provide crucial insights into the infrastructure and processes that sustain the momentum of protest movements, bind participants, and provide purpose, communitas, and continuity. Paying attention to aesthetics takes us beyond the preoccupation of news reportage and security forces with identifying leaders and assessing protestors’ demands. It opens up a view of the everyday production and reproduction of movements, a view into the social lives of movements as artistic fields of action (Sartwell 2010). The study of political aesthetics requires that we consider the histories from which movements emerge and incorporate perspectives that trace continuities and social reproduction into analysis that, sometimes, focuses too much on novelty, spontaneity, and change (e.g., see Mason 2012). Ethnography is particularly useful in this respect. As Caton et al. (2014) show in their ethnography of the Yemeni Arab Spring, the assumption in news media that progressive political protest could best be expressed through “new” cultural forms introduced from beyond the Arab world, such as rap, missed the importance of tribal poetry to the uprisings. In doing so, a key medium for the expression and circulation of the historical grievances that led to the protests was overlooked.

Aesthetics, then, are not the icing on the cake of serious politics. They are politics in action, in process. They offer a means to trace shifts in mobilization and communication, to understand how politics is embodied and performed, expressed in playful mockery or (non)violent resistance. They offer a means through which to connect movements inevitably separated out in analysis by boundaries based on nationality or academic expertise—a means to better understand the articulation of local discontent with authoritarianism, corruption, and politics as usual with global processes of social, economic, and technological change.

Note: In this post I have drawn in part upon arguments and chapters found within the edited volume The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest: The Arab Spring and Beyond (Werbner et al. 2014). I would like to thank my co-editors and the individual chapter authors. A short film that accompanied a recent exhibition of images from the book, and which complements some of the points made above, can be viewed below. I would also like to thank the Focaal editors and Mao Mollona for their input.

The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest: The Arab Spring and Beyond from Veronika Reichenberger on Vimeo

Martin Webb teaches anthropology at Goldsmiths College, University of London. His research focuses on urban civil society activism, transparency, accountability, anti-corruption, governance, and citizenship in Delhi, India.

References

Caton, Steven C., Hazim Al-Eriyani, and Rayman Aryani. 2014. Poetry of protest: Tribes in Yemen’s “Change revolution.” In Werbner, Webb, and Spellman-Poots, Political aesthetics, pp. 121–144.

Cox, Ben. 2014. Umbrella Movement. Film. Brighton, UK: Gnarled Apple Productions.

Manoukian, Setrag. 2011. Two forms of temporality in contemporary Iran. Sociologica 3, doi: 10.2383/36425.

Mason, Paul. 2012. Why it’s kicking off everywhere: The new global revolutions. London and New York: Verso Books.

Moffat, Christopher. 2014. Politics and the meaning of Bhagat Singh. PhD thesis, Cambridge University.

Morris-Jones, W H. 1963. India’s political idioms. In Cyril Henry Philips, ed., Politics and society in India, pp. 133–154. Studies on modern Asia and Africa, no. 1. London: G. Allen & Unwin.

Pinney, Christopher. 2014. Gandhi, camera, action! India’s “August spring.” In Werbner, Webb, and Spellman-Poots, Political aesthetics, pp. 341–367.

Roy, Srirupa. 2014. Being the change: The Aam Aadmi Party and the politics of the extraordinary in Indian democracy. Economic and Political Weekly 49(15): 49–54.

Sartwell, Crispin. 2010. Political aesthetics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Tarlo, Emma. 1991. The problem of what to wear: The politics of Khadi in late colonial India. South Asia Research 11(2): 134–157. doi:10.1177/026272809101100202.

Webb, Martin. 2014. Short circuits: The aesthetics of protest, media and martyrdom in Indian anti-corruption activism. In Werbner, Webb, and Spellman-Poots, Political aesthetics, pp. 193–221.

Werbner, Pnina. 2014. The mother of all strikes: Popular protest culture and vernacular cosmopolitanism in the Botswana public service unions’ strike, 2011. In Werbner, Webb, and Spellman-Poots, Political aesthetics, pp. 222–259.

Werbner, Pnina, Martin Webb, and Kathryn Spellman-Poots, eds. The political aesthetics of global protest: The Arab spring and beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Cite as: Webb, Martin. 2015. “Contemporary Indian anti-corruption movements and political aesthetics,” FocaalBlog, April 23, www.focaalblog.com/2015/04/23/martin-webb-contemporary-indian-anti-corruption-movements-and-political-aesthetics .

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.