Introduction:

The evangelical preacher Joel Osteen, whose nondenominational Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas, attracts an estimated 40,000 worshippers weekly, is often presented as paradigmatic of the ways faith, media, and capitalism intersect in today’s media environment (e.g., Einstein 2008). Osteen’s message is communicated through his best-selling books, CDs, and DVDs; his satellite radio program and television network; and a well-managed Internet infrastructure of platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram; podcasts, direct-marketing emails, a blog, mobile phone apps, and even an iPad magazine (Bosker 2012). In other words, “Joel” is more than a preacher; he is a branded media package. Mara Einstein’s description of a stop on Osteen’s 2004 “An Evening with Joel” tour provides an account of how music begins to work as part of this:

At the start of one “show” at Madison Square Garden, the stadium goes dark. The audience anticipation is palpable. Slowly, the music builds, the audience stands, and rhythmic clapping fills the auditorium. The lights come brightly on, the choir of 80 or more (plus orchestra) begins a rousing number, and Cindy Cruse-Ratcliff and Israel Houghton, musical directors of Lakewood, lead the audience in singing praise. The songs are rock tunes with simple lyrics, which are flashed on overhead video screens so the audience can sing along. Music is an important element in these evenings. It underlines most of the show, functioning as a soundtrack and cuing audience members about appropriate emotional responses. (Einstein 2008: 134)

Einstein describes the way music is used to shape the emotional atmosphere of the event. But this is just part of the larger mediated experience of “An Evening with Joel.” For example, the night was recorded and released on DVD. The songs led by Cruse-Ratcliff and Houghton—themselves both Christian music stars with impressive recording portfolios—were well-known Christian hits, also available for purchase at the event and online. Furthermore, participants recorded the event on their mobile devices and uploaded those recordings to YouTube and other social media sites, their productive agency helping spread Osteen’s message beyond the geographic and temporal confines of the event itself.

Tim Taylor’s (2012) historical study of the different uses of music in American advertising illustrates the development of this convergent media environment and music’s changing role in it. During the twentieth century, the number of media platforms grew to include print, radio, television, and the Internet. Concomitantly, music moved from a largely stand-alone medium to part of a marketing matrix of people, places, commodities, and industries. Today, music’s meaning is often realized as part of a branded ecosystem in a culture where participants “expect” songs to be tied in with, for example, the simultaneous release of a new movie, new product rollouts, and numerous spin-offs and brand extensions. This cultural understanding of music and media is not limited to the realm of entertainment but rather informs the experience of everyday life, of which religion is one aspect. “An Evening with Joel,” while spectacular, was therefore not unique to either highly mediatized evangelical Christianity or consumer culture in general. Rather, the tour deployed communication strategies commonly used in a culture where “every important story gets told, every brand gets sold, and every consumer gets courted across multiple media platforms” (Jenkins 2006: 3). In this environment, music is often used to draw affective connections between disparate platforms. This is a delicate process, one which modern marketers are still trying to understand (e.g., Lusensky 2010). However, one group of entrepreneurs has understood how to leverage the communicative potential of music for more than three hundred years. They are Joel Osteen’s forerunners, the Protestant evangelists of the New World, who used music as part of an integrated, experiential multimedia communications strategy to connect with their stakeholders and spread the Gospel in the religious free market of the United States.

This article suggests that, by tracing the historical intersections of music, marketing, and evangelism in the United States, we can better understand the ways it is used to inculcate the affective ties from which contemporary capitalism—seen especially in “Web 2.0” commercial strategies—derives value (Arvidsson 2006). The United States is often considered the most religious country in the (post)industrialized world, with more than 90 percent of the population claiming belief in a higher power (Pew 2008). Finke and Stark (2005) explain this high rate of religiosity in market terms: the separation of church and state inscribed in the United States Constitution creates a free market in which religious organizations have to compete with one another for adherents. Evangelical churches have historically thrived in this “spiritual marketplace” (Roof 1999) because their entrepreneurial preachers have made their messages relevant and appealing to their target audiences with vernacular language and music delivered through clever uses of media and marketing (Moore 1994). Evangelical preachers in the United States have always been the vanguard of using media and music in entrepreneurial ways. As media technologies have evolved, so too have their communication strategies—all of which have been bound up with the practices and logics of their capitalist environments. The following traces the intersections of capitalism with music, media, and religious experience from its roots in the Colonial Era, when religious revival and hymnal sales went hand in hand; through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that saw the development of “new measures,” such as the construction of purpose-built venues, the embrace of popular music, and the development of evangelical institutions and publishing houses; to the emergence of a new brand of media-savvy, entertainment-oriented evangelists who pioneered professional-level production values, populated the airwaves, and developed niche markets.

Whitefield and Franklin: Publicity and profit in the Colonial Era

The first great evangelist in the New World was George Whitefield (1714–1770). Whitefield was a skilled entrepreneur, an impresario who:

…was a master of advance publicity who sent out a constant stream of press releases, extolling the success of his revivals elsewhere, to the cities he intended to visit. These advance campaigns often began two years ahead of time. In addition, Whitefield had thousands of copies of his sermons printed and distributed to stir up interest. He even ran newspaper advertisements announcing his impending arrival. (Finke and Stark 2005: 88–89)

Whitefield’s media campaigns were both effective and profitable, so much so that none other than Benjamin Franklin became Whitefield’s publisher (89). Whitefield understood how to use media to push people’s emotional buttons. When he arrived in town, the buzz created by his publicity was palpable, and the charismatic preacher channeled this into conversion after conversion. While little is written about Whitefield’s use of music other than that he composed several hymns, the preacher’s revivals led to dramatic increases in the sale of religious tracts for Franklin, including the previously difficult-to-sell hymnals of Isaac Watts (Green and Stallybrass 2006).

George Whitefield, M. A. (NYPL Digital Library)

Finney and Hastings’s “new measures”: Purpose-built venues and popular music

Whitefield was a pragmatist, and Charles Grandison Finney (1792–1875), the “Father of modern revivalism” (Hankins 2004: 137), was more pragmatic still. Finney employed what became known in Protestant circles as “new measures” (although they were not entirely new) that included not only advertising his meetings through the judicious use of handbills, pamphlets, and newspapers but also constructing venues with good ventilation, keeping prayers short, and encouraging participants to leave their dogs and young children at home. He sought to create a worship environment free of distractions, an idea that is central to the ethos of most Protestant evangelical churches today. And like today’s most successful evangelical entrepreneurs, he knew that consumers respond to novelty: “The object of our measures is to gain attention,” he claimed, and to this end “you must have something new” (Finney [1835] 1960: 181, original emphasis).

Charles G. Finney (NYPL Digital Library)

This included new music. Finney’s collaborator, Thomas Hastings (1784–1872), believed that by appealing to worshippers’ aesthetic tastes, one could engage them in the act of worship and through this inspire “the appropriate mix of devotion and piety” (Nekola 2009: 100). Thus, congregational singing at Finney’s revivals was often characterized by new choruses or refrains added to existing hymns of Watts and Wesley. As Anna Nekola points out, these songs were easy to learn and remember, eschewing theological content in favor of “pietistic, emotional, and subjective experience” (93). They were therefore easily incorporated into participants’ personal narratives, especially as elements of conversion to Christianity that Finney and Hastings sought to inspire.

Moody and Sankey: The development of evangelical institutions

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a new generation of celebrity preachers took advantage of developments in media and communications technologies to spread the Gospel. These celebrity preachers built their own venues, started their own publishing houses, and founded educational institutions. Two preacher-musician partnerships that were particularly adept at this were Dwight Moody (1837–1899) and composer Ira Sankey (1840–1908), and Billy Sunday (1862–1935) and his musical collaborator Homer Rodeheaver (1880–1955).

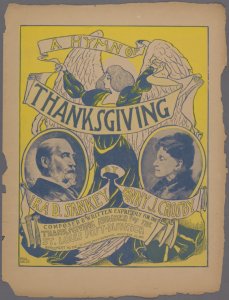

Dwight Moody was a famous preacher and skilled businessman. He recognized that evangelism could take many forms, and to this end he founded what are today known as the Moody Church, the Moody Bible Institute, and Moody Publishers. His collaborator, Ira Sankey, was a prolific composer and publisher in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Moody and Sankey were active during a time when developments in communication and transportation were helping establish the beginnings of a new mass-mediated popular culture in which song was a central text (Taylor 2010). For example, the sheet music to “A Hymn of Thanksgiving” was distributed as a supplement to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 26, 1899 (see note 4 here). Moody’s acumen and Sankey’s music were thus instrumental in developing an ecology of media, people, and institutions in which religious experience thrived.

“A Hymn of Thanksgiving” (1899), composed and written by Fanny J. Crosby and Ira D. Sankey (NYPL Digital Library)

Sunday and Rodeheaver: Evangelism and record publishing in a new popular culture

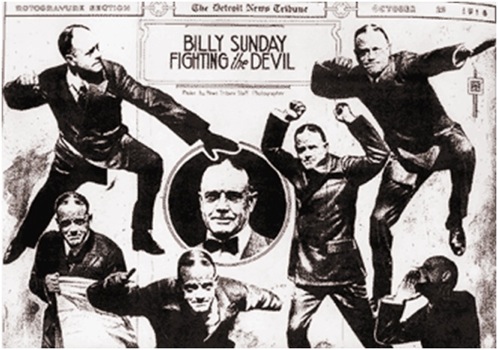

Although Billy Sunday and Homer Rodeheaver were critical of the mass-mediated popular culture that was developing at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, their approach to evangelism was nevertheless very much “in and of” it. In the cavernous tabernacles the preacher had built, Sunday’s theatrical delivery and Rodeheaver’s booming trombone teamed to fight the devil and hold sway over the thousands of faithful for whom mass-media entertainment was increasingly central to daily life. Rodeheaver further utilized the burgeoning printing and recording industries in his evangelistic efforts; he started a successful music-publishing house and later founded Rainbow Records, the first label dedicated exclusively to gospel music (Nekola 2009: 334). The evangelism strategies of Moody and Sankey and Sunday and Rodeheaver were precursors to the largely self-contained church media ecosystems we see today that included purpose-built venues, pastoral education institutions, and publishing companies, all of which consolidate the means of production “in house.”

“Billy Sunday fighting the devil” by photographer from Detroit News Tribune, October 29, 1916 (Wikimedia Commons)

Sister Aimee Semple McPherson: Evangelical media star and radio pioneer

Perhaps no other media technology so thoroughly reoriented ideas of song, intimacy, and the celebrity voice than the radio (Taylor 2002), and the Pentecostal embodiment of this was Sister Aimee Semple McPherson. Sister Aimee was a talented thespian and eloquent preacher, who, in contrast to Sunday’s fire-and-brimstone approach, communicated her message through affirmations and humorous anecdotes. Also in contrast to Sunday, who controlled acoustics in his tabernacles by covering the floors with sawdust, McPherson’s 5,300-seat Angelus Temple in Echo Park, Los Angeles, boasted lush red carpets and a stage large enough to accommodate two choirs and a full orchestra. Her use of professional lighting, imaginative costuming, and entertaining theatrical scripts that she wrote, produced, and starred in captivated audiences (Cox 1995: 123–124). Furthermore, she pioneered the professional-level production values and use of the full range of performing arts that are the cornerstones of many evangelical creative ministries today (ibid.). She was also a pioneer of radio, opening one of the country’s first Christian radio stations, KFSG in Los Angeles, in 1924. McPherson capitalized on the general public’s perception of radio waves as having quasi-transcendent powers—inviting listeners to place their hands on the radio itself while praying (Taylor 2002). Through her broadcasts, she entered into the daily lives of countless Americans.

Billy Graham: Music, evangelism, and niche markets

After World War II, television became a fixture alongside the phonograph and radio in American households. In this new media environment, Billy Graham pioneered the use of music as a tool for Christian demographic and market segmentation, if not in name then certainly in practice (Nekola 2009: 335). Focusing on the “youth market” through his campus crusades, he divided participants into two groups: those who had yet to find Jesus and those who were already saved. He used popular music to attract the unsaved to social gatherings, such as prayer groups and youth conferences, where they might find Jesus. Once they were “saved,” the same music became a resource for the development and maintenance of their newfound Christian identities. Graham’s methods were similar to those of his contemporaries on Madison Avenue, which in the 1950s and 1960s was the Silicon Valley of US marketing and advertising and where people not dissimilar from the popular TV series Mad Men sought to develop emotional, even quasi-religious, ties between consumers and their brands, albeit ostensibly for different reasons. And as we see from those in Madison Square Garden, who started off this article, these methods continue to be refined today.

Conclusion

Evangelists in free markets have historically been the vanguard users of music and media to spread a focused, powerful, and affective message that people deemed relevant to their lives. Put in the language of capitalism: evangelicals have always understood the marketing power of music. Today, the communicative strategies largely developed by New World evangelicals have been adopted and adapted by organizations large and small throughout the world. Furthermore, although evangelical Christian churches are still the most visible marketers, organizations from all of the world’s major religions—and several new religious movements such as the Church of Latter Day Saints, Kabbalah, and Scientology—are following suit.

What do we learn about capitalism by tracing the historical and contemporary uses of music and media in the religious market? Any activity is shaped by, but also plays a role in shaping, its environment. American evangelical Protestants didn’t just use music and media in a religious market: they used it very well and are thus studies in how capitalism worked in their own times. Furthermore, in his classic book Noise, Jacques Attali (1985) suggests that music functions as an annunciator—it not only responds to but also previews and perhaps even prefigures changes in the political economy in which it is embedded. As such, it may behoove us to observe how evangelicals of all stripes use music and media to communicate their ideologies in an increasingly mediated world of contemporary capitalism.

This post was drawn from Chapter One of the author’s PhD thesis (Wagner 2014: 40–48) and indebted to the scholarship of Anna Nekola (Nekola 2009). Thanks to Mark Porter for comments on an earlier version.

Tom Wagner is a teaching fellow at the University of Edinburgh’s Reid School of Music. His work on music and marketing appears in The Australian Journal of Communication 39(1) and in a forthcoming volume, co-edited with Anna Nekola, entitled Singing a New Song: Congregational Music Making and Community in a Mediated Age (Ashgate 2015). Several of Tom’s publications are available here.

References

Arvidsson, Adam. 2006. Brands: Meaning and value in media culture. New York: Routledge.

Attali, Jacques. 1985. Noise: Political economy of music. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bosker, Bianca. 2013. Click “pray” to pray: How evangelical megapastor Joel Osteen is saving souls with Facebook. Huffington Post, May 9 .

Cooke, Phil. 2008. Branding faith: Why some churches and nonprofits impact culture and others don’t. Ventura, CA: Regal.

Cox, Harvey G. 1995. Fire from heaven: The rise of Pentecostal spirituality and the reshaping of religion in the twenty-first century. Reading, MA: Perseus Books.

Einstein, Mara. 2008. Brands of faith: Marketing religion in a commercial age. London: Routledge.

Finke, Roger, and Rodney Stark. 2005. The churching of America, 1776–2005: Winners and losers in our religious economy. Rev. ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Finney, Charles Grandison. [1835] 1960. Lectures on revivals of religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Green, James N., and Peter Stallybrass. 2006. “Benjamin Franklin: Book publisher.” The Library Company of Philadelphia (accessed 6 December 2014).

Hankins, Barry. 2004. The second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press.

Lusensky, Jakob. 2010. Sounds like branding: Using the power of music to turn customers into fans. London: Bloomsbury.

Moore, R. Laurence. 1994. Selling God: American religion in the marketplace of culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nekola, Anna. 2009. From this world to the next: The musical “worship wars” and evangelical ideology in the United States, 1960–2005. PhD diss., University of Madison-Wisconsin.

Roof, Wade Clark. 1999. Spiritual marketplace: Baby boomers and the remaking of American religion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Taylor, Timothy D. 2002. Music and the rise of radio in 1920s America: Technological imperialism, socialization, and the transformation of intimacy. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 22(4): 425–443, doi: 10.1080/0143968022000012138.

Taylor, Timothy D. 2010. The rise of the jingle. Advertising & Society Review 11(2), doi: 10.1353/asr.0.0051.

Taylor, Timothy D. 2012. The sounds of capitalism: Advertising, music, and the conquest of culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. 2008. “U.S. religious landscape survey—Religious beliefs and practices: Diverse and politically relevant.” Pew Research Center.

Wagner, Tom. 2014. Hearing the “Hillsong sound”: Music, marketing, meaning, and branded spiritual experience at a transnational megachurch. PhD thesis, Royal Holloway, University of London.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.