This post is part of a feature on “Debating the EASA/PreAnthro Precarity Report,” moderated and edited by Stefan Voicu (CEU) and Don Kalb (University of Bergen).

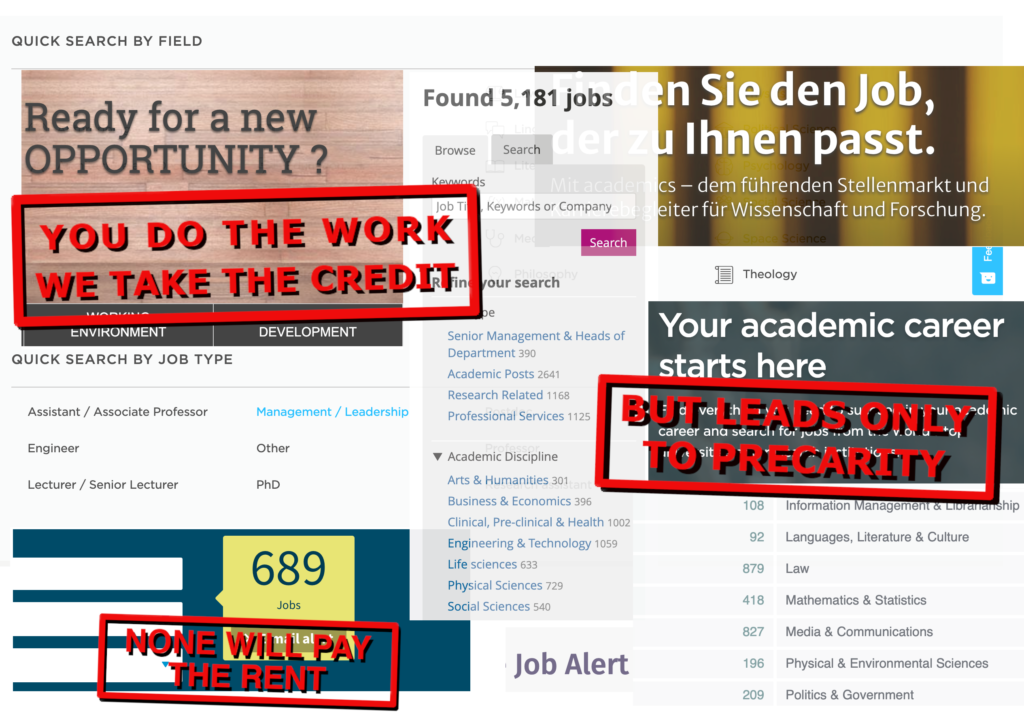

The authors of The Anthropological Career in Europe (Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes 2020) have made visible the inequality and hierarchy that has become increasingly normalized in higher education in Europe. The impact of the report lies far beyond anthropology, and my reflections here build on the report’s key findings and consider the impact of precaritization on the university and academia as a whole.

Precarity is a condition impacting a specific group of people but it is sometimes seen as limited in its impact to them. It is indeed the case that there are groups of people disproportionately affected by strategies of precaritization (and within this, precarity impacts disproportionately on different genders and on racialized groups), but this does not mean that their cases are isolated from the rest of the university or academia at large. There is a case to be made that precaritization of the relatively vulnerable is a portend of and precursor to practices that transform academia overall (as the shutting down of academic departments in the UK and the retrenchment of scholars who, until that moment, would not describe themselves as precarious demonstrates). Precaritization also affects the types of knowledge we produce and the forms of teaching that we value.

It is important to keep in mind that underpinning precarity is a relationship of exploitation and expropriation of intellectual labour. It is a tool that enables the transformation of universities into a space for the accumulation of wealth and prestige. The precaritization of younger scholars serves the interests of a number of people, working both in university management and in academic positions. At stake when thinking about precarity is nothing less than the soul of the university. One way of thinking about precarity in higher education is in terms of moral economy (Cantat, forthcoming): what does precaritization of academics tell us about the values underpinning the distribution of resources in the university? And how does this affect the purpose of the university, its knowledge production, its role in the public sphere, its pedagogies and its boundaries? There are many ways in which this can be thought. Informed by the collective thinking in a forthcoming book, Opening up the University: teaching and learning with refugees, that I’ve co-edited with Céline Cantat and Ian M. Cook (Cantat, Cook, & Rajaram, forthcoming), in this reflection I focus on three points raised explicitly or implicitly in the report, which all relate to how value is formed in the university: precaritization and the ethics of care, precaritization and prestige, and precaritization and unionisation.

Precarity and the ethics of care in higher education

Precaritization is enabled in part because academia is often more than simply a career, it is a commitment to a relation of care whether to our students, our research subjects or to the integrity of research and education itself. The commitment to care is exploitable both by senior scholars and by university managers, as people hang on to academic careers and endure cycles of poor academic contracts because of how they value research and teaching. Care labour is unevenly distributed across the university, with precarious academics disproportionately taking on non-prestigious care work, including the emotional labour of supporting students and the mundane everyday tasks required to ensure the smooth functioning of research projects and departments. Clearly there is a gender element here too, with younger female academics more likely to undertake care labour. The uneven distribution of care labour leaves more senior academics free to pursue activities seen as more prestigious. The devaluation of care labour – as something to be released from – portends the emphasis on acquiring prestige and the transformations this effects across the university.

Precarity and prestige

We must think about precarity relationally. Precarious contracting continues, and has indeed become a standard way of operating in higher education, because it benefits some. These are not just university administrators checking the financial bottom line, but also senior professors whose careers are sometimes built on the precarity of others. As the report shows, large research grants, like those from the European Research Council, are enabled through the work of precariously contracted junior researchers, resulting in “power asymmetry” (Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes 2020: 6). This means that junior researchers struggle to gain durable and independent control of the knowledge they produce.

Power asymmetries can also lead to greater incidences of different forms of harassment, and difficulties in addressing these, because precarious scholars are caught in a relation of extreme dependency with senior scholars on whom their future academic careers depend. Cook (forthcoming) argues that prestige is a form of capital, an accumulation of assets that can be used to enhance one’s relative position, and that it has a structuring quality, meaning that in university settings prestige-capital produces durable patterns which reinforce the accumulation of prestige as a goal of academic work.

University funding practices, and management practices encourage the accumulation of prestige as capital. Here we connect to neoliberalising practices, with individualized competition among academics, and to an audit culture where research is valued in terms of numbers of publications and amounts of research funding gained. Like other neoliberal projects, however, the conditions under which academics compete for prestige capital are uneven. Many may be inclined to participate in research or teaching not recognized by the audit culture and thus not counted in tenure or promotion reviews (Cook, forthcoming). The competition for prestige capital also favors a specific type of academic, one able to dedicate time and energy to acquiring the metrics required and to enact a recognizable academic habitus, and with resources to overcome stresses that impact on mental, emotional and physical health (the lack of attention in academia to mental health issues is telling and troubling).

All this leads to a catch-22 situation for precarious scholars. Their conditions of work impinge on their ability to gain the metricized value that is translated into prestige. Ending precaritization in higher education requires more than the cultivation of good practices in research management. It requires a commitment to rethinking how academic work is valued.

Precarity and unionisation

Anti-precaritization moves can re-invigorate a university union. The Anthropological Career in Europe shows that a number of scholars on short term contracts do not join unions that do not seem to represent their interests or status in the university. Trade unions can, however, be reinvigorated through newly active membership that can cultivate solidarity between tenured and non-tenured staff, including those on short term contracts (by pointing, for example, to normalization and mainstreaming of precaritization and its moral economy in the university). It can also question the hierarchy between “staff” and “faculty”. A project to overcome precarity through unionisation may, however, lead to reinforcing the employee-employer relationship as the most important of all possible and actual relations in the university. University staff and faculty are more than employees, they represent and cultivate the idea of the university. It is through teaching and research and through the ways in which we engage in a day-to-day way with our students that we represent and shape the university, articulate its ethos, and expand its boundaries. An over reliance on unionisation may cede questions about the purposes and value structures in the university to management or to compliant tenured professors (though this depends of course on the shape and depth that unionisation takes).

What is to be done? Precaritization is not an isolated condition. In order to overcome repeated precaritization and its consequences for the mission, ethos, and value of the university, new structures that revalue research and education in different ways should be built (Cantat, forthcoming). One way to start is for established, tenured scholars to divest from the structures that foster careers on the backs of precarity and to be willing to render themselves vulnerable alongside precarious scholars.

Prem Kumar Rajaram is professor of Sociology and Social Anthropology at Central European University and Head of CEU’s Open Learning Initiative (OLIve) which provides education pathways for people of refugee backgrounds. He is a co-opted member of EASA’s Executive Committee.

Bibliography

Cantat C. (forthcoming). “The politics of university access and refugee higher education programs? Can the contemporary university be opened?”. In Cantat, Cook, & Rajaram (eds.) Opening up the University: teaching and learning with refugees. Forthcoming.

Cantat, C., Cook, I.M. & Rajaram, P.K. (eds.). (forthcoming). Opening up the University: teaching and learning with refugees.

Cook, I.M. (forthcoming). “Fuck Prestige”. In Cantat, Cook, Rajaram (eds.). Opening up the University: teaching and learning with refugees. Forthcoming.

Fotta, Martin, Mariya Ivancheva and Raluca Pernes. 2020. The anthropological career in Europe: A complete report on the EASA membership survey. European Association of Social Anthropologists. https://easaonline.org/publications/precarityrep

Cite as: Rajaram, Prem Kumar. 2021. “The Moral Economy of Precarity.” FocaalBlog, 9 February. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/02/09/prem-kumar-rajaram-the-moral-economy-of-precarity/

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.