This post is part of a feature on “Debating the EASA/PreAnthro Precarity Report,” moderated and edited by Stefan Voicu (CEU) and Don Kalb (University of Bergen).

The EASA membership survey and the associated ‘precarity’ report (Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes 2020) are an important and timely contribution. Surely these are findings we must build on and the critical scrutiny of which is indispensable for formulating minimally shared lines of action. The report is likely to stir discussion both through its inclusions as well as through some of its inevitable silences. It is some of the latter that I want to briefly touch upon here.

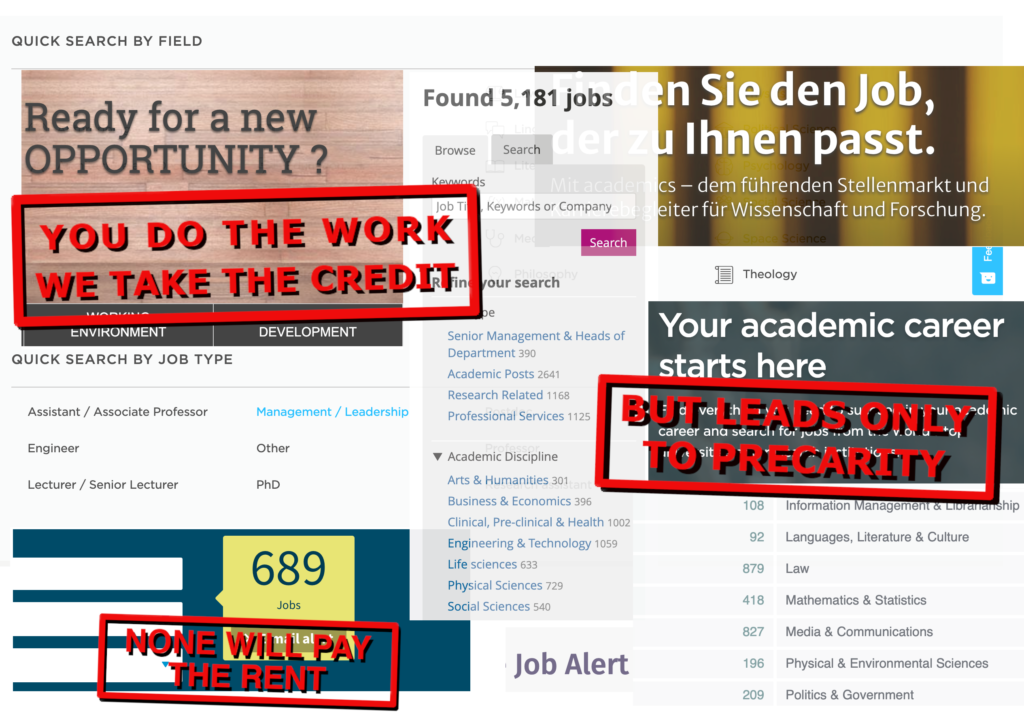

The report paints a grim picture of precarity and increasingly precarious lives for the majority of the younger practitioners of the discipline. The authors of the report are well aware of the limitations arising from their sampling, but the inclusions and exclusions operating alongside it are more than a matter of survey design. They speak to the structural properties of an academic field as much as to the way in which the field can be represented and spoken for. Two of the divides that the authors identify are also at work as principles of organization of the very report, given the marginal presence of those categories among the respondents. First, the geographical North-South/West-East divide and, second, the middle and upper-middle class/working class divide. Regarding the former, we learn from the report that out of 809 respondents, German and UK residents each provide more than 100 of the responses. Combined, these two countries provide almost one third of the respondents, while residents of East Central and South Eastern Europe combined add up to a total of only 9.7%. Regarding the class divide, the authors remark that almost two thirds of the respondents come from middle class families.

The overrepresentation of Western European residents and the underrepresentation of Eastern and South Eastern ones receives two explanations in the report. The first, in a footnote on page 22, explains the overrepresentation of British and German respondents (by residence) through the size of the national population and that of anthropology programs, a distinctly unconvincing explanation absent other data to support it. As a matter of fact, aggregate data on the size of the academic market suggests that countries such as Spain are underrepresented in the survey sample. While I do not have access to quantitative data on anthropology programs, in 2018, the year of the survey, Spain had, in absolute numbers (85,000), the second largest doctoral studies sector in the EU after Germany, and was followed by France, another severely underrepresented country in the survey sample. While the distribution for tertiary sector graduates by broad field of study is for many reasons an unreliable proxy for assessing the size of the distribution by discipline of PhD students, it is worth noticing that while among the total number of tertiary-sector graduates social science graduates in Germany comprise 7.5 % of the total, a figure comparable to the Spanish 7%, the EASA reports includes 119 respondents from Germany and only 34 from Spain. This is in wild contrast to the only roughly 25% higher number of social science tertiary sector graduates in Germany as compared to Spain‒in absolute numbers).

Another, more convincing explanation, is offered in the attempt to explain that two of the most equal countries in terms of income distribution among anthropologists working in academia according to the survey data appear to be Russia and Romania. This, rather than reflecting an actual equality of income distribution, the authors suggest, has a straightforward answer: “it is likely that the individuals from Russia or Romania who could afford to be EASA members or attend EASA conferences were those already in the higher-income brackets for their country” (Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes 2020, p. 57). The latter sounds a lot more convincing and is certainly an all too familiar reality for non-Western anthropology students.

Whether it is the underrepresentation of Eastern and South Eastern Europe or the overrepresentation of Western and Northern Europe that is more politically salient is a matter that requires a broader discussion. But with regards to what explains the underrepresentation, a few words must be said about exclusions from EASA membership. A reality that will make some blush, since no one is supposed to talk about this, is the fact that EASA membership categories look like upper class scribbles in stratification theory: out of the three income categories the bottom one, from 0 to 24,999 euro, grants yearly membership at the cost of 40 euro. Surely few would imagine that life at the lower and the upper end of this interval looks similar. The alternative seems quite straightforward: how about 0 income – 0 fees?

Other aspects of underrepresentation unfortunately do not have such simple solutions. The reality of EASA is that for an association that calls itself European it is a surprisingly monolingual one. That a discipline the practitioners of which pride themselves on their ability to learn local languages have so easily accepted the hegemony of English as the language of academic exchange is a troubling state of affairs. And in places such as Spain, where I currently reside, it means an important barrier. This barrier works in two directions: it not only excludes local anthropologists, but it also favors the export of knowledge production from the periphery to the core: put otherwise, learning diverse European languages is good enough for the export of raw data, but not important enough to lead to a genuinely cosmopolitan exchange in terms of academic production.

On matters of class divisions and questions of representation the reality encountered is even tenser. The authors of the report express concern over the underrepresentation of working-class members and also raise legitimate concerns about the professional opportunities of working-class colleagues.

“If experiences of insecurity, overwork and anxiety about the future are frequent among those from more secure backgrounds, there should be a greater concern about how little protection, job satisfaction and ability to negotiate workloads those coming from working-class families can afford” (Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes 2020, p. 69).

This well-meaning if borderline paternalistic observation is followed by a more fortunate formulation:

“(…) combined with the increase in student fees and the decrease in support for PhD studies, the costs of conference attendance and fieldwork, as well as the broader cuts that anthropology has experienced in the neoliberal era and with the 2008 crisis, the findings call for reflection: they posit the serious and urgent question of how students from working-class backgrounds are encouraged or discouraged to pursue university education, doctoral degrees and academic careers, not only in anthropology” (Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes 2020, p.69).

More caution should have been employed in assuming that the class distribution revealed through EASA membership is a reliable proxy for the class distribution in the discipline at large. We should also tread cautiously when we infer, in the voice of the middle and upper-middle class, what it might mean to be an anthropologist of working-class background. In Spain a common experience is that of the grinding of working-class lives not only through exclusion, but also through inclusion into academic spaces. And while the authors of the report seem to imply that working-class students are at risk of being increasingly underrepresented, there is at least one level at which we are likely to see an increase of the presence of working-class students: the doctoral level. The precarious young, of both working and middle-class origins, are increasingly looking to either civil service or academic spaces for a modicum of stability. In a world of increasing exploitation, while the middle-class is understandably disappointed with the career prospects anthropology offers, the stability of a four-year PhD scholarship of roughly 1000 euros offers many of working-class background the possibility of more stability than most alternatives.

The search for this, however, begins not at the doctoral stage, but as early as the first year of undergraduate university education, where students in their early 20s are already competing for the highest grades and attempting to publish so that they would secure a funded PhD position. A reality which, as former student militants recognize, has significantly contributed to the dissipation of the student movement and the energies required to sustain it. Otherwise put, anthropology might be threatening working-class students not only by shutting the gates of access, but through the deceitful incorporation into the professional lottery.

To be sure, these are typically the students that get by with significantly fewer resources than their middle-class colleagues, and that have more, not less ability to negotiate workloads, if fewer resources to do so. That this might consume a person in a way it does not consume a middle-class colleague is of course a classed reality inscribed onto bodies. Increased abilities but diminished resources do not change the fact that the professional machine will probably spit out the student of working-class background at the first opportunity: but that cut out point seems to be increasingly moving towards the post-doctoral phase, where the prolonged subsistence on no or below subsistence level income requires resources that are less likely accessible to colleagues of working-class background.

Natalia Buier is a graduate of the Sociology and Social Anthropology department of Central European University. Her current research interests include financialization of infrastructure and connections between capitalist social formations and ecological crises. Her new research project addresses the relationship between water scarcity and labor relations in export-oriented agriculture in South Western Spain.

Bibliography

Fotta, Martin, Mariya Ivancheva and Raluca Pernes. 2020. The anthropological career in Europe: A complete report on the EASA membership survey. European Association of Social Anthropologists. https://easaonline.org/publications/precarityrep

Cite as: Buier, Natalia. 2021. “What sample, whose voice, which Europe?” FocaalBlog, 27 January. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/01/27/natalia-buier:-what-sample,-whose-voice,-which-europe?/

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.