Fifty years after student protests shook much of the Cold War world, in the “West” and in the “East,” “Global 1968” has become the catchphrase to describe these profound generational revolts. West Berlin, Paris, and Berkeley spring to mind prominently, and most memorable behind what was then the Iron Curtain were the events of the Prague Spring. For most commentators and scholars, these events in the Global North appear to have constituted “Global 1968.”

At the beginning of the anniversary year, for instance, a recent publication by a German scholar of contemporary history, Norbert Frei (2017), dubbed 1968: Youth Revolt and Global Protest made it to the front tables of major Berlin bookstores. Frei’s monograph includes chapters on Paris, and on the events in the United States, Germany, Japan, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom in “The West,” supplemented by a chapter on “Movements in the East,” which discusses protest in Prague, Poland, and the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Frei mentions neither the events of the “1968” revolts in Africa, nor indeed those that had taken place in any part of the Global South. What then, I am wondering, is his concept of the “global” of the revolt?

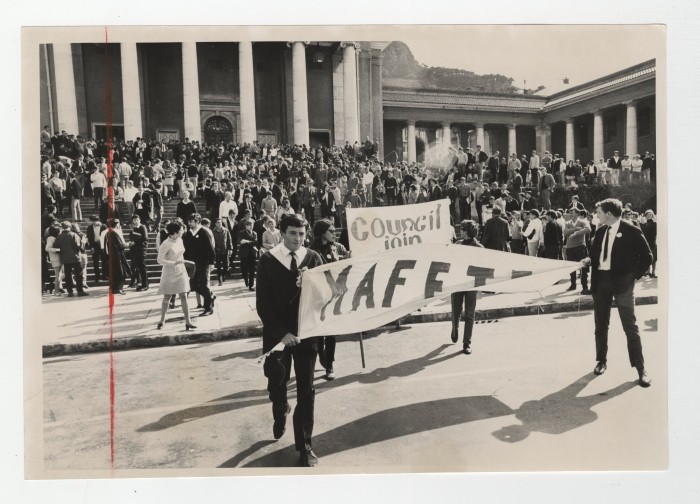

UCT 1968 sit-in protest: marching from Jameson Hall to the Administration Block (photograph held by UCT Photograph and Clipping Collection—Special Collections, University of Cape Town Libraries, used with permission).

Though obliterated in Frei’s monograph, Latin America gathers a little more attention with the 1968 events in Mexico City, which are occasionally mentioned in the discussion (Carey 2016; Kurlansky 2005). In contrast, none of the relevant overviews brings related events on the African continent to the fore.

What may be the reason for the fact that in the current debates on “1968” and its legacy on the African continent are almost never mentioned? It certainly was not the case that nothing happened on the continent that matched the activism of the revolting generation elsewhere. In fact, students in a range of African countries appear to have contributed to the global uprising with their own interpretations, from Senegal and South Africa to the Congo (Monaville 2013), to mention just a few. Yet, those African revolts and protests have been forgotten in the global discourse of commemoration.

There is clearly a great need to look more closely at African events, trajectories, and meanings of 1968 activism. For a start, here are two vignettes of student protests that come to mind; both took place in 1968 on the continent. The first uprising happened in Dakar, the second in Cape Town.

Student-led protests against rising food prices and neocolonialism: Dakar 1968

The majority of those celebrating and debating in the Global North may be surprised to hear that in May 1968, it was not only France where a student-led revolt almost sent a government packing, but that this also happened in Senegal. In Dakar, students had been on strike from March 1968, initially criticizing the conditions in their university. From April 1968, they connected with broader concerns in the society, such as the high price of local staples, the fall in the standard of living, unemployment of graduates, and foreign domination of the domestic industry. In May 1968, the Senegalese trade unions adopted the students’ slogans and joined the struggles. Leo Zeilig (2007: 182), who has studied the Senegalese protests in the wider context of African student movements, describes the events of Dakar 1968:

On demonstrations the crowd declared: “Power to the people: freedom for unions,” “We want work and rice.” The coalition of student and working-class demands culminated in the general strike that started on 31 May. Between 1 and 3 June “we had the impression that the government was vacant . . . ministers were confined to the administrative buildings . . . and the leaders of the party and state hid in their houses!” . . .

The government reacted to the strike by ordering the army onto the university campus, with instructions to shoot on sight. During a demonstration after these events, workers and students decided to march to the presidential palace, which was protected by the army. French troops openly intervened, occupying key installations in the town, the airport, the presidential palace and of course the French embassy. The university was closed, foreign students were sent home and thousands of students were arrested.

There has been some discussion among former activists and analysts in how far the events in Dakar were connected to those in Paris. Although it seems clear that they were certainly no distant ripples of the storm in the French metropole—and in fact, the students in Dakar had taken to the streets before those in Paris—authors like Zeilig maintain that they were indeed part of the global 1968 youth revolt.

Today, the events that took place in Dakar between March and June 1968 are seldom debated as central foci of a global 1968 protest movement. This is ever-more surprising as the brutal crackdown on the uprising in Senegal sent ripples to Europe. In September 1968, thousands demonstrated against the “Peace Award of the German Publishers’ Guild” to Senegalese President Léopold Senghor during the Frankfurt Book Fair. The protests were explicitly directed against both Senghor’s concept of Négritude said to ostensibly promote neocolonial development and the brutal crushing of the Senegalese opposition movements earlier that year (T. Brown 2013: 117–120).

Yet, the events in Dakar were related to Global 1968 and those in the country’s former colonial capital, Paris, in a more complex ways than suggested by those who claim that “the French events . . . found their way quickly to Dakar” (T. Brown 2013: 118). The Senegalese movement not only began earlier, it was connected also to local histories of protest. In February 1961, 250 students had taken to the streets of Dakar to protest against the assassination of the Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba. Analysts suggest that this was the moment when the Senegalese students shifted from an anticolonial orientation toward an anti-imperialist ideology (Bianchini 2002).

African uprisings in 1968 also need to be considered in the context of broader waves of student activism and rebellion on the continent. Again, events in the Congo were central to this as the assassination of Lumumba radicalized student politics with an impact on both the local, the African, and indeed the international (Global North) student movements. In West Germany, for instance, long before the massive protests against Senghor at the Frankfurt Book Fair, students had been marching in West Berlin against an official visit of Congolese President Moise Tschombé in December 1964, who was said to have been implicated in the murder of his predecessor, Patrice Lumumba. On the African continent, as elsewhere, student revolt took different forms in response to varying local, national, and regional conditions. Yet, the late 1960s saw protests in countries across Africa.

Student protests against apartheid and institutional racism: Cape Town 1968

South Africa too had its 1968 moment of transgressive student activism (J. Brown 2016). At the country’s oldest university, the University of Cape Town (UCT), Archie Mafeje, a black master’s graduate of UCT (cum laude) and by then in the process of completing his PhD at the University Cambridge, was appointed in 1968 to a senior lecturer position in social anthropology. The university offered him the job, but then, after government pressure by the Apartheid regime, rescinded the offer.

The issue was discussed at the congress of the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), which organized most of the UCT students at the time, and the idea emerged of a sit-in along the lines of the university occupations then taking place in the rest of the world. Some of those who were involved remember that the European protests were widely reported in South Africa and that students followed them with interest (Plaut 2011).

So when the university authorities failed to stand up against the government intervention in its hiring policies in August 1968, a mass meeting took place in the university’s grand Jameson Hall, normally the site of graduations and other academic events. After rousing speeches from student leaders, most of the one thousand–strong audience marched out, and about six hundred students occupied the university’s administration building. The “sit-in” of students and some academic staff, as the action was called following the designation of similar forms of activism from Berkeley to West Berlin, resolved “to sit in this Administration Building until such time as the University Council has met to 1. Appoint Mafeje to University Staff. 2. Make a statement of policy to ensure that the future appointments be made solely on Academic grounds” (BUZV UCT). While the form of activism was thus fairly radical, the language of the protest, with its emphasis on “academic freedom,” remained within the limits of liberal opposition against the apartheid regime. Significant for the South African political and academic condition of the time is further that most if not all of the student protesters belonged to the country’s white minority.

Eventually, the occupiers—about 90 had stayed the course—gave up and left after one-and-a-half weeks. A white anthropologist was appointed in Mafeje’s place. South Africa’s oldest university had caved in to the demands of the apartheid policy regarding university education.

The 1968 “Mafeje affair” must be understood as representative of the enforcement of apartheid policies in the academy. From 1959 onward, South African students had been admitted to universities along racial and ethnic lines—at UCT, which had been declared a white institution, black students were admitted only under exceptional circumstances and any “nonwhite” applicant aspiring to study at UCT had to apply for a special permit from the government. Although this law did not pertain to academic staff members, Mafeje’s appointment was prevented.

Yet, for a brief period in August 1968, South Africa had had its taste of “1968.” Martin Plaut (2011), one of the occupiers, described this action of a section of South African white students:

Six hundred of us decided to participate in the occupation, determined not to leave until UCT reversed its decision. For ten days we held out, sleeping on the floors. Food was cooked communally—even by the men who, at that time, were largely ignorant of the workings of a kitchen. Plenty of wine and marijuana were consumed and virginities were lost, but on the whole it was a carefully managed protest, with a sign asking for rubbish to be removed and the areas being occupied to be kept clean. Messages of support flowed in from students in Paris and London and there was favourable coverage in the international media.

Perhaps the most important thing was that we discovered intellectual liberation. Alternative lectures were organised on the stairs. We got a newspaper up and running. In one fell swoop we had thrown off our mental shackles. At last we were not just some isolated racist outpost of empire, but part of an international student movement.

UCT 1968 sit-in protest: inside the occupied administration block (photograph held by UCT Photograph and Clipping Collection—Special Collections, University of Cape Town Libraries, used with permission).

This conclusion was indeed significant: the student protesters felt that through their transgressive activism they had gained a sense of intellectual freedom and self-respect, which the academic institution, proud though as UCT was and remains of its “liberal” stance, had not been able to maintain.

The events in Dakar and Cape Town demonstrate examples of students on the African continent revolting in very different ways and contexts than those in the North American and Western European settings. The comparison of these two instances of the many uprising in Africa’s 1968 also shows the diversity of settings and forms of activism on the continent. The unfolding of those events and the fact that they were met with solidarity and related protests in the Western centers of the revolt highlight that Africa should not be left blank on the map of scholarship that seeks to understand 1968 in a global perspective.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was published on Heike Becker’s blog.

Heike Becker is Professor of Anthropology at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa. She writes about the intersection of culture and postcolonial politics, particularly on memory politics, popular culture, and social movements in southern Africa. Her recent publications include “Un/making Difference through Performance and Mediation in Contemporary Africa” (2017), a special issue of the Journal of African Cultural Studies, coedited with Dorothea Schulz.

References

Bianchini, Pascal. 2002. “Le mouvement étudiant sénégalais: Un essai d’interpretation.” In La société sénégalaise entre le local et le global, ed. Momar Coumba Diop, 359–396. Paris: Karthala.

Brown, Julian. 2016. The road to Soweto: Resistance and the uprising of 16 June 2016. Johannesburg: Jacana.

Brown, Timothy Scott. 2013. West Germany and the global sixties: The anti-authoritarian revolt, 1962–1978. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BUZV UCT. Photograph and Clipping Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries, Special Collections. “Academic Freedom—1968: Sit-in Protest.” mss_buz_acad_freedom_1968_sit_in.

Carey, Elaine. 2016. “Mexico’s 1968 Olympic dream.” In Protests in the streets: 1968 across the globe, ed. Elaine Carey 91–119. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing.

Frei, Norbert. 2017. 1968: Jugendrevolte und globaler Protest. Munich: dtv.

Kurlansky, Mark. 2005. 1968: The year that rocked the world. London: Vintage.

Monaville, Pedro A.G. 2013. “Decolonizing the university: Postal politics, the student movement, and global 1968 in the Congo.” PhD diss., University of Michigan. http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/102373.

Plaut, Martin. 2011. “How the 1968 revolution reached Cape Town.” MartinPlaut blog, 1 September. martinplaut.wordpress.com/2011/09/01/the-1968-revolution-reaches-cape-town.

Zeilig, Leo. 2007. Revolt and protest: Student politics and activism in Sub-Saharan Africa. London: I.B. Tauris.

Cite as: Becker, Heike. 2018. “‘Global 1968’ on the African continent.” FocaalBlog, 9 February. www.focaalblog.com/2018/02/09heike-becker-global-1968-on-the-african-continent.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.