I spent the last weeks of August and the first days of September in Hungary, close to the European Union’s border with Serbia. Never before had a routine field trip catapulted me into an engagement with issues dominating daily headlines, both in Hungary and elsewhere. What light can social anthropology throw on the current “migrant crisis”?

Introduction

A late-summer field trip to Tázlár, a village in southern Hungary I have known for forty years (population circa 1,750 and falling), is usually a matter of catching up with friends and grasping local events and narratives against the background of national developments. In 2015, things were different. What villagers and their neighbors in the market town of Kiskunhalas (population circa 30,000 and falling) were talking about reflected not only national headlines but also the dominant news story throughout Europe. This is variously labeled the crisis of the “migrants” or “refugees” or “asylum seekers.” In Hungary as elsewhere the vocabulary one uses may imply a political opinion. During these summer weeks, this small country (population circa 10 million and falling) became a flash point for anxieties endemic throughout western Europe. The crisis led to mutual reproaches between states and laid bare deeper problems of governance and political economy. Before turning to analyze and reflect on these larger issues, let me begin with the local details where anthropologists are typically more comfortable. To contextualize my ethnography from Tázlár and Kiskunhalas, it is necessary first to outline the distinctive profile Hungary has cultivated since Viktor Orbán became prime minister for the second time in 2010.

Background

I arrived in Budapest ahead of the celebrations of St. Stephen’s Day, a major public holiday on 20 August. The rituals were by and large familiar (I witnessed them for the first time in 1972, when the holiday was known as Constitution Day). This is above all a celebration of Hungarian statehood. Stephen was the king who converted his pagan people to Christianity and established a presence at the heart of Europe that has endured all vicissitudes for more than a millennium. Following the Népvándorlás (or Völkerwanderung, “migration”) that brought Hungarian tribes to the Carpathian Basin, Stephen’s decision to convert was opposed by rival chiefs. His main opponent, Koppány, warned against subordination to other powers, notably Germans. Laborc objected to “a God who does not speak Hungarian,” to quote a dramatization of the conflict in a rock opera first performed in 1983. The music of Levente Szörényi and the lyrics of János Bródy have had an impact on popular culture that persists after more than three decades. In 1983, for a small country of the Soviet bloc, the attractions of the West and “Europe” were overwhelming. Things are more complex in 2015, when the aging rockers starred in a spectacular open-air revival of their work that brought mixed reviews, including some sharp commentaries about nostalgia and cultural resistance. If the applause for Koppány and his allies was particularly vigorous in 2015, this was due to not only the quality of individual songs and performers but also the widespread perception in the audience that this small nation is nowadays exposed to new forms of colonization—from Europe and the capitalist West.1

After attending this concert on 19 August, I followed the more formal speeches and ceremonies the next day. As expected, migration and “security” issues were prominent. Significant numbers of refugees had been visible for months in Budapest’s public sphere, notably in the “transit zone” at the recently refurbished plaza in front of the monumental Keleti train station. The government had responded with attempts to prevent “illegal migration,” notably through the construction of a barbed wire fence along the southern border with Serbia, the transit route for most of these unwelcome strangers. Just about all Hungarians are aware of the opprobrium this fence has brought them in other European countries. But Orbán and his government have defended their actions. Large billboards all over the country proclaim, “We do not want illegal immigrants.”

This billboard is one of a series visible nationwide in 2015 with the general slogan “The Hungarian reforms are working.” The text in the bubble reads, “We do not want illegal migrants.” (Photo: Government of Hungary)

The ugly fence, they insist, is necessary to ensure that migrants cross the border where they are supposed to. They further claim that they are abiding by agreed EU norms (the Dublin convention) in taking fingerprints and registering those who declare they wish to seek asylum in the EU. Officials point out that in most cases, this should already have taken place in Greece, where the new arrivals first entered the EU. In short, the authorities claim to be acting as good Europeans. At the same time, in the speechmaking on 20 August, the nationalist tone was unmistakable. The prime minister’s principal representative spoke of an increasingly insupportable burden for the nation and for Europe, while at the morning military ceremonies, the defense minister declared, “This is our homeland, not some sort of house with a passageway through it.” By contrast, in the main religious rituals late in the afternoon, when the sacred relic of Stephen’s right hand processed through the streets around the basilica named after him, Cardinal Péter Erdő invoked Stephen’s teachings to call for a more tolerant approach to solving the problems posed by the unprecedented deluge of immigrants.2

Ethnography

Tázlár lies on the Great Plain midway between the rivers Danube and Tisza, about a half hour’s drive from the Serbian border. The village is just to the east of the international railway line between Budapest and Belgrade. The migrants who reach the EU here, usually crossing the border on foot, are doubtless surprised that long stretches of the railway, constructed in the late nineteenth century under the Habsburgs, are still single-track.

The Tázlár–Kiskunhalas road where it crosses the international rail link between Budapest and Belgrade.

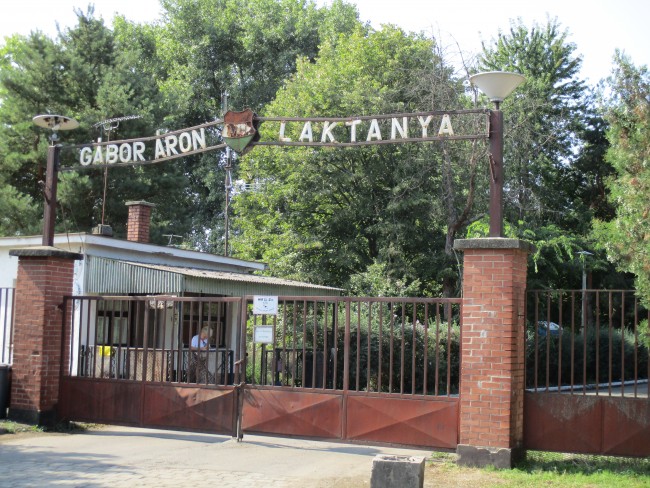

There was no question of improving it during the socialist era, when the Yugoslavia of Marshal Tito was long considered a threat. In Kiskunhalas, the socialist state invested not in the railway but in barracks, including one that housed Soviet soldiers until 1990. That complex is now a housing estate, but in summer 2015, a large Hungarian barracks just outside the town was adapted at short notice to serve as a temporary camp for asylum seekers. Those brought here are not visible in the city center, and not even accredited journalists have been allowed access. I was therefore unable to verify rumors about violent conflicts (the use of tear gas was commonly asserted) at this former barracks, allegedly between the immigrants and Hungarian security officers and between rival immigrant groups.

As in the town—in Tázlár, too, just fifteen minutes away—I found that no one had actually seen an asylum seeker in the flesh. This did not prevent villagers from vouching an opinion. Views were not uniform, but the majority referred to migrants rather than refugees and endorsed the critical voices of government officials. Some asked, if all these strangers were really political refugees from Syria, why had they disposed of all documents that might confirm their identity? Why did they object to the registration process and insist on being allowed to proceed to Germany? Why did they all seem to have smartphones of a quality to which few villagers could aspire? Why did the women seem to flaunt their gold jewelry, evidently worth more than the price of a house in a declining village like Tázlár? When posed on Facebook, the answer to this last question came promptly: obviously because this portable form of wealth is all that the family has left in the world. But many continued to argue that those who could afford to pay substantial sums for their illegal journey to Germany, however physically arduous, did not deserve friendly support and charitable donations from the Hungarian population. Some villagers wrote abusive comments on Facebook, urging the government to adopt violent methods to put an end to the fiasco and protect the integrity of the nation’s territory.

A few individuals were more sympathetic. Some pointed out that modern Tázlár was itself a community formed by immigrants in the late nineteenth century, many of them not ethnically Hungarian. One Lutheran spoke of his disappointment with the inadequate responses of the country’s larger Calvinist and Catholic churches and criticized the government’s recourse to anti-Islamic rhetoric. Similar sentiments were present in another minority: atheists, some of whom might have been members of the Communist Party in the past. Several interlocutors pointed out to me that, with Hungary’s population in long-term decline, there was actually an economic need for more labor—and that Syria might be a suitable place to recruit, better in terms of a well-educated labor force than most other regions of the Arab-speaking and Muslim worlds. Public polls indicate that opinions vary according to contemporary political preferences. Two-thirds of those who support the Hungarian Socialist Party, the successor to the Communist Party, would like to put a decisive end to the current immigration stream. This figure reaches almost 80 percent among supporters of Orbán’s party, Fidesz, and is just below 40 percent among Democratic Coalition supporters, but this party has virtually no support in villages like Tázlár.

One local Fidesz member, educated in the socialist era, had an elaborate theory of how anonymous capitalist forces, banks, and institutions such as the IMF were behind the influx. The true purpose was to dilute labor markets and maintain profit rates for multinational companies. Others, however, questioned the readiness of these migrants to work at all, or at any rate to perform the kind of labor that lies at the heart of local morality. In sweltering conditions at the end of August, villagers have jobs to do in their fields and vineyards. Despite mechanization, some grapes and berries must still be harvested by hand.

For a ten-hour day, a laborer in Tázlár takes home less than 20 euros. In Tázlár and Kiskunhalas, as throughout the country, many are glad to be offered the opportunity of workfare, since the alternative is unemployment. Participants include citizens who have completed secondary and even higher education, for whom workfare at home is the only alternative to unskilled work abroad or day laboring. The rate of remuneration is less than half of that earned by a day laborer, but most prefer a workfare place because it confers health and pension entitlements. Disadvantaged Hungarians (but also those in jobs that are more comfortable) perceive that the invisible strangers who pass through their settlements in illegal taxi journeys at the dead of night are on the way to a paradise called Germany. There, the state will provide them with more daily pocket money from the moment of their arrival than they could ever earn as honest day laborers in a Tázlár vineyard or as street sweepers in Kiskunhalas.

Television interviews (for which journalists inevitably seek out migrants with whom they can find a common language) confirm the suspicion that many of these migrants are well-educated, ambitious young people, typically hoping to pursue their studies at a German university. Viewers compare these upbeat prospects with those of their own children and grandchildren, EU citizens but deprived of German munificence and generally lacking the linguistic skills necessary to seek a job abroad that would correspond to their qualification.

The end of my sojourn coincided with the climax of the crisis in the first week of September. When I returned to the capital, I found that trains to Germany from the Keleti station were canceled. Mingling with tourists and other Schaulustigen, I took a few quick pictures of those who had been enduring atrocious conditions in the plaza. They were increasingly strident in their demands to be allowed to leave for Germany, where Angela Merkel had declared they would be welcome. I was eventually able to leave from another station and (after taking two local trains) caught my international express from the Slovak border station. This train had lots of empty seats and couchettes. At no stage in my journey back to Halle was I asked to show an identity card or passport. During the following days, the immediate crisis eased as migrants were finally allowed to leave the Keleti transit zone. They were greeted by cheering crowds when they arrived at train stations in Vienna and Munich, where government ministers proclaimed a Willkommenskultur and condemned Hungary’s handling of the crisis.

Analysis

This account, completed within forty-eight hours of my return to Germany, is based on my recollections, written notes, and newspaper cuttings. But anthropology is more than ethnography. We may have much in common with diarists, tourists, and journalists, but we are also social scientists. It is never enough to report local voices and to describe events: we should be concerned to explain them, in cooperation with other social scientists. Some of the more fruitful directions for cooperation are implicit in the above descriptions: social psychology, sociology, political science, and political economy.

For example, we can surely find partners among sociologists, not just in the specialized field of migration studies but also among those versed in the more general comparative literature on social inequality. Perceptions of vulnerability and relative deprivation may be more important causes of political attitudes and social behavior than absolute poverty or inequality. A generation ago, in the last decades of socialism, Hungarian society was in many respects buoyant and ebullient, at least when compared with its socialist neighbors. Economic statistics show progress in many fields after 1990, and especially since the country was admitted to the EU in 2004 and became eligible for large subventions in numerous sectors. Even in Tázlár, more and more residents have telephones and computers, and the number of private cars continues to rise. But these vehicles tend to be old and cheap, and the local housing market reveals a depressing story. The owners of properties built in the prosperous years of socialism can no longer recover the cost of their materials when they try to sell. Jobs are scarce and the population continues to decline. Government statistics present a positive picture for national employment trends but only by including workfare participants and those working outside the country. The policies of Orbán’s governments, including their increasingly belligerent nationalism, are evidently connected to the new political economy—and to the fact that the most significant opposition in recent years has come not from the left but from Jobbik, a party even further to the right. In summer 2015, the salience of the migrant crisis diverted attention from persisting economic difficulties and numerous corruption scandals.

The sociology of the media is another subfield in which anthropologists should seek partners. Throughout this year, as everywhere in Europe, sensitive issues have been highly mediatized. The ratio of journalists to migrants at the Keleti station was rather high. When one considers the much higher numbers of Syrian refugees now living in Turkey, the “European migrant crisis” of summer 2015 seems grossly exaggerated. During my stay in Tázlár, I paid attention to coverage in the principal media in both Hungary and Germany, sometimes comparing TV news reporting on the same day. There were some striking contrasts. When Hungarian state television informed its viewers that the country was taking fresh initiatives to implement the Dublin agreement, viewers of ARD or ZDF were told that Orbán was continuing his intransigent policies by refusing to allow migrants free passage westward. When, on 31 August, controls were temporarily lifted (after Merkel was understood to have proclaimed that all Syrians were welcome in Germany), authorities in Budapest were immediately pilloried by German reporters for passing the buck to their western neighbors. At moments like this, it was hard not to feel a little sympathy with the beleaguered ministers in Budapest, who were damned whatever they did.

In both countries, private TV channels helped to draw attention to the diversity of opinions in the respective populations. But the tone was set by the public stations, and I found the main state channels in both Hungary and Germany to be rather homogenous. Of course, their hegemonic views were entirely different. Some of the notes struck in Hungary were discussed above. It would be shortsighted to conclude that villagers derive their prejudices mechanically from the biased media coverage. Rather, local lifeworlds in recent decades predispose the majority to sympathize with the interpretations they are offered. I think the relation in Germany between producers and consumers of news pertaining to the migrants is different. One Hungarian put her finger on this when she commented on a gulf between the messages coming from Berlin and the liberal media and the views of ordinary German people: “Germans are the last people on Earth to welcome the kind of pollution these immigrants bring with them, so what is going to happen when they are forced by their own high-minded elites to live alongside them?” Pollution here was intended to refer to the dirt of unwashed bodies but also to the insidious spread of Islam. When I was asked to confirm the truth of such views, I responded feebly that I am not German myself and have not undertaken any research in German society.

This is true, albeit cowardly. I do live in Germany, and in summer 2015, I do have the impression, especially from news and documentary programs on the ZDF channel, that German viewers are exposed daily to didactic campaigns to correct the stereotypes put forward by that woman in Kiskunhalas. It is not the case that foreigners sponge off the state, since statistics show that, overall, non-Germans are net contributors through the taxes they pay. It is not the case that foreigners take the jobs of native Germans, as evidence shows they fill significant gaps at both ends of the labor market. But it is the case that Germany has an urgent need of demographic replenishment to maintain the standards of living (and pensions) to which its citizens are accustomed. So, quite apart from humanitarian considerations, a rational scientific case for welcoming the immigrants, based on economics and demography, is presented in the public sphere as overwhelming. Anyone taking a different view is tarred with the brush of the PEGIDA movement, or worse.

The PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the Occident) protest originates in the former East Germany. Widely publicized opinion polls indicate that, indeed, negative attitudes toward the new immigrants are significantly more common in the neue Bundesländer. In other words, the recriminations generated by the new Völkerwanderung, which have already soured relations of Budapest with Berlin and Vienna, are likely to continue within Germany. This has implications for cities such as Halle, where I have lived for the past sixteen years. Germany does not distribute asylum seekers according to where they might one day have prospects of finding work in a dynamic regional economy. In economically depressed regions, a large influx of strangers is almost certain to cause social problems. In this respect, East Germany is structurally similar to the Visegrád Group of former socialist countries, which have declared themselves unwilling to accept binding EU quotas as a means of coping with the current crisis. The Hungarian position is no different from that of Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. If there were still a government to reflect the views of the population in the former East Germany, this would surely be its position, too.

All this seems to me to add up to a dangerous situation for democracies. We might theorize the problems in terms of “society” versus “civil society.” I met Viktor Orbán in 1989 when he was in Oxford with a scholarship to explore the latter concept under the guidance of political philosopher Zbigniew Pelczyński. Due to fast-moving developments in Budapest that year, Orbán cut short his stay among the ivory towers. He had an election to fight. In those years, a free civil society was the aspiration of the party he led, and perhaps of most Hungarians. I was more skeptical, fearing that the new slogan would be a cover for the domination of the market and all the inequalities that capitalism was sure to bring in its train. The consequences can now be evaluated after a quarter of a century. Instead of basking in the sunshine of Western recognition for helping to put an end to the Iron Curtain (notably through allowing East Germans free passage to the West), Hungary is now castigated for building a new fence and curtailing the free movement of people in need of humanitarian assistance. Hungarian “civil society” is visible in front of the Keleti station in the form of Migration Aid and other NGOs that have struggled against the odds to alleviate the human consequences of government policies. But Hungarian “society” overall remains critical, even scornful, of all these developments. In short, the migrant crisis is accentuating polarization within Hungary and is exploited by the right to intensify nationalist sentiment.

Is a comparable divide being widened in German society? Germany is different both because of its unique history and because it has been the major beneficiary of recent economic trends, including the creation of the euro. The combination of these factors leads the dominant elites to take a very different stance. Civil society is active here, too: the media pay great attention to the voluntary charitable action of citizens concerned to help in any way possible, ehrenamtlich. But it seems to me that these interventions remain somewhat out of kilter with the views of the wider population. With a majority of journalists located in the red–green zones of the political spectrum (perhaps comparable to the figure for academic social scientists), Merkel can be sure of significant support for her present policies. Most anthropologists will also be glad to sign up. But we are also the discipline expected to shed light on those sections of society with which others do not so readily engage. I have heard East Germans complain that the present television coverage is reminiscent of the “black versus white” worldviews to which they were subjected under Erich Honecker. Today’s media regime is equally far from reflecting their lifeworlds. This gives rise to the sensitive charge (because of Nazi associations) of Lügenpresse (“press of lies”). Is it the media’s task in a democracy to educate readers and viewers and ultimately bring them around pedagogically to see the world as their more enlightened elites see it? When populism has long become a term of abuse, how can anthropologists present a typical PEGIDA supporter’s worldview with the discipline’s conventional empathy? Should we at least point out that the higher incidence of anti-immigrant sentiment in the East correlates with higher rates of unemployment and other forms of discrimination? If voices such as those I have heard in Tázlár and Kiskunhalas exist in the villages and small towns of Germany (and also in cities such as Halle), it would surely be good to hear them, as a prelude to understanding and explaining them.

Eurasia

Europe has been a leitmotif throughout this summer. At the peak of the crisis, Orbán has reaffirmed that he thinks and acts as a Christian European. Whatever view one takes about these claims (personally, I find them distasteful), the chaos of recent weeks has illustrated yet again the inadequacy of EU institutions and has done further damage to tendentious notions such as “European values.” Regular readers of this blog know where I think the solutions lie: the new Völkerwanderungen can only be addressed through a pan-Eurasian coming-together of peoples, as a prelude to a true world society.

There are many levels of irony in the fact that the flash point in recent weeks should be Hungary. Hungarian reform communists did much to pave the way for a new and freer Europe twenty-five years ago and in particular for the reunification of Germany. Fidesz leaders have not sought to make too much capital out of this contribution, since it had nothing to do with them. But in the summer of 2015, they were not expecting to find Hungarians depicted in such negative terms by Germans and Austrians. The Magyars are a people with obscure origins who migrated from Asia to the Carpathian Basin, where their language makes them distinct from all their European neighbors. Yet their government today, like the rest of the Visegrád Group, expresses no interest in the problems of Asia. Apart from Syria, it is widely reported that Afghanistan is the main origin of the asylum-seeking masses. The convulsions in these countries have many causes. All need to be addressed. The combined political, economic, and ethical–social issues demand solutions at the level of the landmass. Ethically, it is hard to agree that future immigration levels from Afghanistan to Germany should be determined by the figure necessary to ensure that the gulf between living standards in Afghanistan and Germany should remain as it is today. The same point can be made closer to home, for example, with respect to Kosovo. It is time to forge new political institutions to put an end to the current hypocrisy of development (most of the foreign capital that has flowed into Syria and Afghanistan over the years has taken the form of weapons rather than socioeconomic well-being).

Unfortunately, this is not going to happen just yet. In southern Hungary, only the plan to upgrade the railway link between Budapest and Belgrade has a Eurasian dimension. Alas, this is a narrowly economic one. The contract has been provisionally awarded to a Chinese firm, and the capital and labor necessary will come from China. It seems that the scheme has already been approved in Belgrade, but in summer 2015, Budapest politicians were still prevaricating.

Conclusion

The late Raymond Firth used to describe social anthropology as an “uncomfortable” discipline. This was very different from the neo-Marxist diagnoses fashionable when I was a student, according to which anthropology was a significant handmaiden of capitalist imperialism. Times have changed, but I think Firth’s characterization remains apt. I felt an unprecedented personal degree of discomfort in recent weeks, partly caused by the fact that representations in the mass media in Hungary and Germany brought my field site into a peculiar relationship with the society in which I live and work. Anthropologists, like other academics and the journalists discussed above, are human beings who may bring their own values to bear on their work. In the field, they may prefer to cop out when they can, as I did when declining to endorse stereotypes about contemporary German society in Kiskunhalas. In Germany, by contrast, I find myself having to explain to friends and colleagues that many individuals and groups organized humanitarian aid to migrants in Budapest, just as they have seen on their televisions Germans and Austrians in Vienna and Munich. Making Orbán the scapegoat and demonizing his government is too simple a way for Germans and other Europeans to reassure themselves that they still have the moral high ground. Not all Hungarians are nationalists or potential fascists, and the propensity to help suffering strangers is not so different from what one finds in German society. If there are some significant differences between the two countries in the spectrum of political opinions, these should be analyzed with reference to history and contemporary political economy.

I would be concerned if highly mobile, multilingual students and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, irrespective of their specific research focus, were not inclined to write indignant letters of protest to the Hungarian ambassador at this moment. I shall be heartened if they wish to show their solidarity with underdogs and downtrodden victims—and not only when such people present themselves on our doorstep in a German city. Beyond these personal ethical commitments, we have a dual scientific agenda. In one dimension, we try to understand other points of view, including those in our own society with which we may disagree and even find repugnant. In the other dimension, it is necessary, in collaboration with other scholars, to investigate and explain the deeper causes of the processes currently tearing communities apart and creating new social divisions, with worrying political implications, right across Eurasia and globally.

Chris Hann is Director of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany. He is currently leading the ERC project “Realising Eurasia: Civilisation and Moral Economy in the 21st Century.”

This text was first published on 7 September 2015 on the REALEURASIA Blog: http://www.eth.mpg.de/3932117/blog_2015_09_07_01.

Unless otherwise indicated, all photos in this post are credited to the author.

Notes

1. The composers of the work are widely identified with different political orientations. Whereas Szörényi has championed the national cause, Bródy is identified with more liberal, cosmopolitan tendencies. In an interview on the eve of the 2015 performances in the conservative Magyar Nemzet, the latter declared diplomatically that it was in the national interest for the modern successors of Stephen and Koppány to find the elusive balance that would allow Hungarians to be Europeans without becoming a colony.

2. Two weeks later at a press conference, the cardinal’s tone harshened when he declared that organs of the Roman Catholic Church in Hungary were not legally empowered to lend support to illegal migrants. Shortly afterward, Pope Francis urged Catholic parishes throughout Europe to do exactly this. In Hungary, many lay Catholics and clergy have been active despite the hierarchy’s stance; monks at Pannonhalma in Transdanubia were active in assisting refugees to leave the country for Austria.

Cite as: Hann, Chris. 2015. “The new Völkerwanderungen: Hungary and Germany, Europe and Eurasia,” FocaalBlog, 11 September, www.focaalblog.com/2015/09/11/chris-hann-the-new-volkerwanderungen-hungary-and-germany-europe-and-eurasia.

Discover more from FocaalBlog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.